Roch Castle, Pembrokeshire

A Study in Significance

Peter Holden and James Meek

|

||

| Roch Castle photographed from the north-east just before completion of the project |

If the intervention is to find its place, it must make us see what already exists in a new light (Peter Zumthor, Thinking Architecture, 2006)

Cadw, the Welsh government’s historic environment service, defines conservation as ‘the careful management of change’ in its Conservation Principles (2011). The same publication also states that ‘to be sustainable, investment in the conservation of the historic environment should bring social and economic benefits’. With dwindling state aid, a sustainable future for historic buildings in Wales must be underpinned by economically viable use.

Conservation Principles goes on to describe the significance of a historic asset as embracing ‘all of the cultural heritage values that people associate with it, or which prompt them to respond to it’. Assessing the significance of a place can involve subjective decisions based on emotional responses. To the client it may mean one thing, to the archaeologist or preservation group another. It often falls to the architect to assess conflicting evidence in order to evaluate significance.

Cadw’s principles also state that new work or alteration to a significant place will normally only be acceptable if ‘there is sufficient information comprehensively to understand the impact of the proposal on the significance of the asset’ and ‘the quality of design and execution add value to the existing asset’.

The conversion of a Grade I listed building to a new use can only be successfully achieved through a mutually respectful partnership between architect, archaeologist and conservation officer. This is especially true when the building in question is an early medieval castle like the one at Roch in west Pembrokeshire. The project benefited throughout from the support and positive input of the conservation department at the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority.

As with all ancient buildings, the fabric records a story of change that reflects historical, political and social developments. The challenge at Roch Castle was to understand the extent of the surviving medieval work and to evaluate the significance of the more recent alterations.

ROCH CASTLE – THE STORY SO FAR

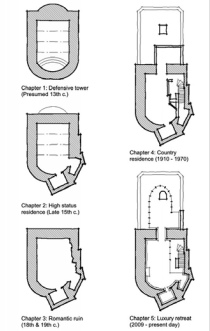

Roch Castle was one of a number of defended sites along the ‘Landsker line’, the boundary between the English, Flemish and Norman settlers of southwest Pembrokeshire and the ousted native Welsh to the north and east. Originally a simple stone tower perched on an outcrop of igneous rock, its unusual D-shaped plan-form (‘chapter 1’ in the diagram, below left) was probably an engineering solution to the shape of the rock rather than a stylistic convention. It was constructed by the descendants of a powerful family of Flemish settlers in the 13th century, and the castle remained in the hands of the descendants of Godbert the Fleming (the de Rupe and de la Roche families) until the 15th century.

|

||

| Roch Castle: phases of use from the 13th century to the present day | ||

|

||

| Photograph of Roch Castle from the south-east taken before 1900 (Haverfordwest Records Office) |

The square tower and stair extension on the south-east side of the castle were added when the defensive role of the castle diminished and it became a high status residence (‘chapter 2’). By the latter part of the 15th century the castle was in a ruinous and deserted state. Between 1643 and 1645, during the English Civil War, it changed hands between the Royalist and Parliamentarian forces four times and suffered cannon damage. It was not extensively repaired and by the 19th century (‘chapter 3’) it was a ruin.

The castle was purchased by Sir John Wynford Philipps (later Viscount St Davids) in 1899. He instigated extensive restoration works in the first two decades of the 20th century, including the addition of a three-storey extension on the northern side of the tower, and the installation of new floors, stairs and internal divisions (‘chapter 4’).

In 1954 the castle was purchased by John Whitfield and it was occupied by his father Lord Kenswood and his family until 1965. The castle was then sold to Hollis Baker, an American furniture manufacturer. The latter two owners, Kenswood and Baker, were responsible for the ‘baronialisation’ of the interiors. Photographs taken in the mid 1950s show a series of additions attributed to Kenswood. These include, significantly, black painted gothic doors with false strap hinges (by Baldwin’s of America) and leaded light internal screens.

The last phase of alterations was carried out by David Berry who, between 1972 and 1985, closed off two stairways and reorganised partitions to facilitate separate holiday lettings of the annexe and tower.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION

At the start of the project an initial desk-based assessment and building appraisal was undertaken by Dyfed Archaeological Trust field services to support the planning and listed building consent applications. The aims of this work were to gain further information on the present state of preservation of the castle, provide an indication on the surviving medieval fabric of the building and make an assessment of its archaeological importance. Some research was undertaken into the castle’s date, ownership and historical development, and the subsequent report also provided further information on the known archaeological and historical character of the surrounding landscape.

Further works undertaken at the castle have included a scheme of detailed historic building recording, including survey and photography. This has been supplemented with information recorded during various archaeological watching briefs and a geophysical survey within the grounds.

The historic building recording work has established that the majority of the exterior castle walls is substantially of medieval fabric, although many of the internal and external wall facades were restored during the early 20th century. The recording work has confirmed that the original D-shaped tower had at least two upper floors and a basement area, which was partially occupied by the rocky outcrop. It is likely that this was first built in the early years of the 13th century by Adam de Rupe. Access to the original tower would have been at the first floor level on the north side. Originally, internal stairs were present within the thickness of the walls on the apsidal end of the building, although these were later modified when the square tower addition and stair extension were built on the south-east side of the castle. These extensions contained small bedchambers or solars (private sitting rooms) and guardrobes (latrines).

The medieval floor arrangements differed significantly from those inserted during the early 20th century works with the first floor hall having a much higher ceiling. By the 14th century, large windows had been inserted of which the stone corbelled arches survive, although the actual windows have been heavily modified and replaced. Similar arches over windows and doorways survive on the ground floor of the tower, although these are probably late medieval additions, modified in the early 20th century. The square tower is likely to have been added in the 14th century. The second storey of this tower retains an original rib-vaulted ceiling.

During the early 20th century works, new floors and room divisions were added. The circulation routes and stairs that exist in the building are a mix of medieval and early 20th century additions.

THE OWNER’S BRIEF

|

|

| View of the castle from the south-east |

Roch Castle was purchased in 2009 by the Griffiths-Roch Foundation with the intention of repairing the building and converting it into one of a chain of retreats, all in historic buildings, operated by the Retreats Group Ltd.

Raised in St Davids, the owner (a commercial architect based in Hong Kong) knew the building well and was keen to preserve its history, architecture and importance to the landscape of the St Davids Peninsula. His plan was to introduce all the facilities associated with five star accommodation in the heart of the medieval building using careful design to protect and enhance its significance.

From the outset it was clear that there were potential conflicts and challenges inherent in this approach, not least:

- introducing new functions and spaces without damaging the integrity of the old

- controlling damp ingress to an acceptable level without changing the aesthetic of the castle

- managing safe access and egress without introducing fire escapes

- accommodating new hidden services runs within and without

- minimising future maintenance, particularly at high level

- defining the junctions between new and old.

CONSERVATION AND CONSTRUCTION ISSUES

The liberal use of concrete renders from the early 20th century restoration works has not aided the survival of the castle, which is recorded as having long-standing problems with water ingress and damp. These were serious enough to cause some occupiers to leave. The application of an asphalt coating to the flat roofs and parapet walks helped but, as with the use of cement-based pointing, it proved to be a short-term fix at best.

Encased in cement by Viscount St Davids and in glass fibre by later owners, permission was given at an early stage to allow the removal of linings, cement renders and pointing. This would allow a better understanding of the story of the development of the castle and its condition, prior to an application for listed building consent.

As work progressed, the extent of the damage caused to steel beams and unprotected reinforced concrete (RC) work became apparent. Roofs were formed from concrete cast in situ onto vaulted corrugated steel sheets between RSJs. The breakdown of the asphalt covering had severely damaged the corrugated steel and the top flange of the RSJs. The RC floor slabs had been built directly into the damp walls and had been cast with too little ‘cover’. (Over the years, dissolved carbon dioxide from the atmosphere progressively reduces the alkalinity of the concrete which protects the steel reinforcement. The thickness of the concrete over the steel is therefore critical to its durability.) Concrete analysis showed that in all of the concrete floors, the depth of carbonation exceeded the concrete cover to the reinforcement, suggesting that all of the reinforcement was by this time liable to ongoing corrosion.

The engineer’s report concluded that the extent of the damage to the reinforcement and the structural steel, and the degree to which it had been built into the masonry, meant that in situ repairs would be impractical.

|

||

| Typical corrosion of floor slab reinforcement |

On the other hand, the replacement of the floors and roofs would mean the loss of all the 1950s alterations and much of the Viscount St Davids restoration of 1910. There was a general consensus that the 1950s work was of little architectural or historical value.

The archaeologist had already concluded that the 1910 alterations had not adhered to any of the original floor levels or staircase locations and most of Viscount St Davids’ architectural details had been lost during the later work. The significance of his involvement, certainly as far as the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings was concerned, revolved around what was perceived as an early use of in situ concrete work in west Wales.

Justification for removal rather than repair of the RC structure by the architect was based on:

- the identification of much better examples of early RC work in west Wales such as those at Caldey Island Monastery (1912) and the Towy Works, Carmarthen (1907-9)

- the long-term maintenance implications of not replacing the floors

- the likely effects of any collapse and the resulting damage to the medieval fabric should corrosion continue.

After a prolonged debate, consent was eventually granted. It was conditional on the specific testing of each slab and the development of a method statement for the removal of the floors (from the bottom up) aimed at preserving the integrity of the castle walls.

INTERVENTION

|

|

| New lime render on the staircase walls |

Repairs and alterations were designed to ensure that the surviving medieval fabric was protected and consolidated, and new work was designed with reversibility in mind. Structural components such as roofs, for example, were attached to the structure, not built into it, so that if necessary the new components could be removed with minimum disruption to earlier fabric.

The external repair of the medieval fabric using matching Pennant sandstones and hydraulic lime mortars has been extensive and time consuming. Internally, the masonry walls have been plastered with hemp lime plaster.

Last repointed in sand and cement in the early 20th century, all the pointing has now been renewed in hydraulic lime (NHL 3.5) and sand mortar. The main body of the medieval tower has been hacked out to an average depth of 60mm and pointed in three ‘passes’. The final coat was trowled and brush finished over much of the rubble face work in what is locally known as a ‘parged’ finish. In addition the 15th-century square tower on the exposed south face has received two shelter coats of the same mix, brush applied. The roughly coursed masonry of the 20th-century annexe has been flush pointed in two passes.

To avoid confusing the history of the building, the internal fit-out is uncompromisingly modern, incorporating polished limestone floors, glass screens with aluminium frames and bespoke joinery. In the one location where the new interior extends outside, in the form of a structure which tops the annexe roof (see title illustration), the modern vocabulary is continued, although it interacts with the original fabric by reflecting the D-shaped form of the original tower.

This dialogue between new and old is continued internally through the use of hemp lime plasters for many of the new suspended ceilings and partitions.

Completed in the autumn of 2011, it is hoped that the quality of the repairs and alterations will sustain the next chapter in the life of this important building, both physically and economically.