Sand Cast Lead

Jonathan Castleman

|

| A church roof of sand-cast lead dating from the 1800s which is still performing well. (Photo: Jonathan Castleman) |

Lead is one of the earliest metals known to man and has been in use for some 7,000 years. The English lead mines worked by the Romans are well known, and sheet lead has been used in this country for roofing since Saxon times. Christopher Wren wrote to a friend when choosing lead to cover the dome of St Paul’s, ‘Lead is certainly the best and lightest covering and being of our own growth and manufacture, and lasting, if properly laid for many hundreds of years.’

Lead was used extensively for roofing buildings in the medieval period, especially in the late 14th and in the 15th century when the open timber roofs of flat pitch were developed. Many examples of lead roofs from this period exist today, although the lead covering is likely to have been recast since it was originally laid. The oldest surviving lead sheet on a roof is likely to date from the 17th and 18th centuries, although it is rare to find examples from before the middle of the 18th century. Among examples of original work of this period still in excellent condition, are the roofs of St Paul’s Cathedral, Westminster Abbey and York Minster.

Until the invention of the milling process at the end of the 17th century, all lead used on buildings was sand cast. This cast lead was of considerable thickness, usually far thicker than that used on buildings today. It was not until the 19th century that milled lead (or rolled lead as it is now known) came into common use.

Lead is one of the most corrosion resistant metals and is therefore at little risk of being attacked by polluted atmospheres. Although lead has a tendency for expansion and contraction on roof slopes, it is an almost ideal material for roofing and gutters. Lead can be easily worked into shape, easily jointed and fixed, and is readily available.

Flatter pitched roofs are better suited to lead as there is reduced stress on the material when expansion and contraction takes place. If properly laid however, lead can also be used on steeply pitched roofs.

Cast lead is available in the thicker codes only, codes 6 (2.65mm), 7 (3.15mm) and 8 (3.55mm). At these thicknesses lead is commonly considered a heavy roofing material, however a cast lead roof is lighter than most slate or tiled roofs and is of a similar weight to thatch or asphalt.

Experienced architects and plumbers are of the general opinion that cast lead lasts longer than milled lead, although there appears to be no scientific explanation for this. One reason given is that having been poured over open sand beds, it sets in its natural form without any built-in stresses.

REPAIRS

|

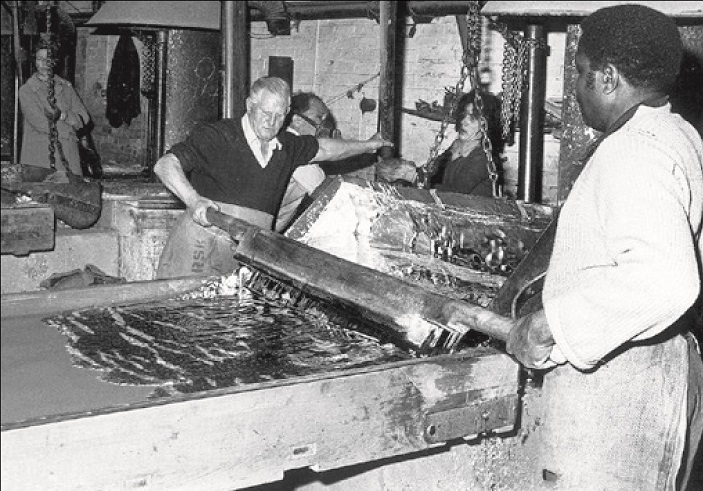

| Two photos taken in the 1950s showing (left) the sand bed being carefully finished with hand-held copper planes ready for casting (right) (Photos: Jonathan Castleman) |

|

It is a key principle of conservation work that as little should be changed as possible, so any new materials required should match the original. Where lead is concerned, this is best achieved by using same production methods, so where original old cast lead roofs must be renewed, the new material should be cast rather than milled, and alternative materials should only be used where essential. This is particularly important where roofs of steep pitch are visible from the ground.

One of the most common causes of defects in lead sheet is wear and tear caused by thermal movement. Lead has a low mechanical strength and is liable to crack or split when subjected to continuous expansion and contraction. Other common causes of failure include structural issues where the timber substrate under the lead has failed, poorly designed or inadequate fixings, and underside corrosion caused by a reaction between the timber substrate or by poor ventilation under the lead.

When lead sheeting becomes worn or split it can be repaired by lead welding, and it is only when it is beyond repair that the lead needs to be removed, recast and relaid, making it one of the most recyclable materials around. This can give rise to considerable savings over completely renewing a roof.

THE ART OF SAND CASTING LEAD

Today, cast lead is manufactured following the same basic methods as that which the Romans used to cast their lead.

The process of casting lead starts with scrap, collected from various sources. The collected scrap lead is then inspected for signs of solder because the material has a lower melting point than lead, creating problems in the casting process and a weak point in future. Any solder patches or soldered joints on pipes are therefore cut out and set aside for further reuse. The lead sheet is then loaded into gasfired pots for melting down. The melting point of lead is 327°C (621°F). When the lead reaches melting point any impurities which are ingrained in the lead float to the surface and are skimmed off and collected, and this waste material can then be sold separately to another company for refinement, so nothing is wasted.

Once the molten lead has been skimmed, it is cast into ingots. This is done by hand ladling the molten lead from the pot into ingot moulds, with each ingot weighing approximately 40kg. These are then taken to the casting area, ready for the next step in the process.

In essence, producing sand cast lead consists of throwing molten lead down a bed of prepared damp sand. This method has changed little since Roman times and the equipment needed is very basic. A predetermined amount of sand is watered and thoroughly mixed using wooden paddles, it is then roughly spread across the casting table. The sand is then roughly levelled off with a bar of wood called a strickle or strike which is propelled by two men at each end and supported by the side beams of the table. The strickle/strike is then used to ram the sand to make it solid again, before being drawn across the table again to level it off at the required level. The surface of the sand is then ready for smoothing to the required finish using handheld copper planes.

|

| The same process today; apart from the dust masks and protective overalls, little has changed. |

While the sand is being prepared for the casting, the lead in the melting pot has been brought up to the required temperature. This is then ladled into a trough at the top end of the casting table. When sufficient lead has been transferred, the trough is lifted by means of a pulley wheel and handle, and the molten lead is poured down the surface of the table. While the lead remains molten, and again using the same strickle/strike, the lead is planed off to give its required thickness. This is determined by a number of factors, namely the speed at which the lead is thrown down the table, the heat of the metal and the speed with which it is planed off, but it also has a lot to do with the experience of the craftspeople involved in the casting. The excess lead is collected in the tail pan and is then transferred back into the pot at the head of the table for recycling.

As soon as the men with the strickle/ strike reach the bottom of the table, the lead behind them has already set and can be marked and cut virtually immediately. All the lead used from the casting is measured for each specific job and is cut to size, rolled and weighed individually. Any lead then left on the table is cut up and again recycled.

In addition to being used on roofs, cast lead is also used for rainwater goods, heads and downpipes. If these are required with mouldings and patterns, a timber pattern is used to press into the sand on the table before the molten lead is thrown. These are then cut out and formed by hand into the pipes and heads as required.

The result of this process is that cast lead is often less uniform than milled lead, its quality depending entirely on the craftsmanship of the person who casts it. Today, however, there are skilled craftspeople spread across the country producing cast lead which complies with the recommendations and proposals of the British Standard Institute codes, and quality is strictly controlled, typically to ISO 9001 quality management standard. The thicknesses of their produce can easily meet the code’s recommendations of plus or minus five per cent, which assures architects and specifiers that they can recommend this material with confidence. To ensure quality specifications will often state that the lead must be from a manufacturer with the appropriate BBA Agrément certification and that it meets the relevant British Standard and the criteria set by the relevant code.

If a cast lead roof is also laid to good standards by a fully trained craftsperson, the normal life expectancy for this remarkable roofing material is at least 200 years. Sand cast lead is without question the ultimate choice when specifying the finest covering for historic buildings of significance that requires a long and service free cover.