Setts and the City

Cobbles, setts and historic townscape

Colin Davis

|

|

| The new cobbles being hammered in |

The setting of a historic building is as important as the building itself. English Heritage and the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment have repeatedly stressed the importance of understanding and conserving ‘the complete picture’ of a given site or space.

Yet, very often, the quality of the setting, clearly visible in old photographs, is now completely lost. This is particularly true where public streets form part of the setting because the materials that make up the road break up over time and have to be changed. Original road surfaces have often been replaced because they failed, or covered over with new materials because they were considered to be inadequate for modern conditions.

Likewise, historic footways have usually been replaced because they have cracked or broken up completely. Typically, stone paving slabs that might have been in place for 200 years only failed when heavy road vehicles became more common after the Second World War. There are exceptions. Places that are inaccessible to vehicles often retain their original paving. Usually these places are in raised areas, such as at the entrance to a church beyond a flight of steps, or completely raised sections of pavement.

There are also many places where original road surfaces, usually granite setts (small rectangular paving blocks), are intact but have been covered up. They are there to be re-discovered just under the modern surface. Historic drainage channels and large granite kerbs likewise often remain. This is because they are both practical and robust and, of course, difficult to move.

To identify the original materials in a particular street, it may be helpful to look at the adjacent private courts or access roads as well as old photographs. These courts and private roads are less frequently changed so many still have their original granite slab tracks for wheels and small cobbles at the centre which served to give the horse traction.

CAUSES OF FAILURE

The most common cause of failure in historic road and pavement surfaces lies not in the visible surface but in the supporting or base layer below it.

Stone is strong in compression, making it difficult to crush, but weak in tension, allowing it to crack or split. In road construction it needs to have a continuous underlying support. The weight of a vehicle is transferred through the top layer of stone to the base below. If the base collapses, the stone surface has insufficient support and then also collapses. The individual setts in a historic road surface may still be intact but they will have fallen apart leaving the whole road surface unusable.

RADCLIFFE SQUARE, OXFORD

|

|

| The new cobbles before hoggin dressing |

Radcliffe Square is at the centre of historic Oxford. It is surrounded by Grade I listed buildings, notably the circular Radcliffe Camera (c1750). The square is made up of public streets with a central fenced oval of grass next to the Camera. There is a low volume of traffic, but there are occasional heavy goods vehicles which deliver to the adjoining colleges.

The public street was surfaced in small round river cobbles set in a compacted hoggin (a mixture of clay, sand and gravel) and some areas of granite setts, also in hoggin, with traditional Yorkstone pavements at most edges. This surface was laid more than 150 years ago. Since the 1960s the cobbled surface had begun to fail. The cobbles themselves were not damaged, but they had become loose and large potholes had appeared. These potholes had been filled either with areas of new cobbles set in regimented rows in concrete, or with areas of square setts, or simply with blacktop.

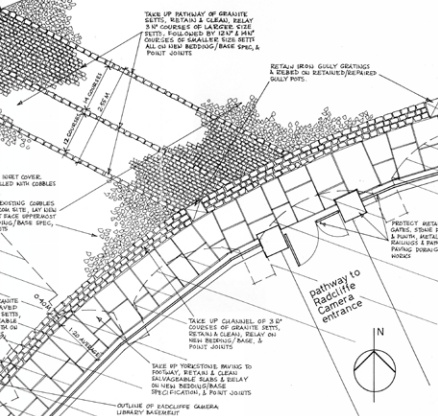

Once an area of cobble was dislodged to form a pothole, the hoggin became unstable and the pothole grew. By 2005 the potholes, both new and patched, covered a wider area than the surviving original cobbles. The conservation objective was to reinstate the historic visual effect of the original surface while creating a robust road surface. The solution was to prepare a measured drawing of all the ground surfaces, take up the remains of the original surface and then replace them exactly as the drawing indicated, but with a base specifically engineered to withstand heavy vehicle traffic.

|

|

Measured drawing of the existing layout at Radcliffe Square, Oxford |

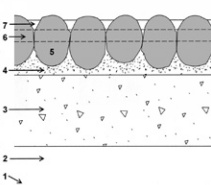

From the bottom upwards this specification (see section diagram, below right) was:

-

Class 6F1 capping, a selected fine grade material

-

150mm type 1 granular sub-base

-

175 cement bound material category 3 (CBM3)

-

70mm SteinTec bedding mortar BM 04

-

70mm x 100mm river cobbles hammered into the bedding mortar to the correct level

-

SteinTec jointing mortar HD 0.2 between cobbles

-

20mm locally-sourced hoggin top dressing.

The original cobbles were some 50mm in diameter and were laid on their side and pressed into the hoggin. To achieve the same visual effect, larger cobbles were used, but laid on their ends, so that only the tips of the cobbles could be seen. When the original hoggin was re-applied as a decorative top dressing the overall appearance was virtually the same as the original. The complex specification was designed to ensure that the new cobbles were firmly fixed. Being both round and smooth there was a danger that they would be pushed out sideways by the severe lateral pressure of the power-assisted steering of modern heavy vehicles.

Considerable time and effort were taken to make sure that the finished appearance was accurate and pleasing. Three test samples were undertaken in the workshop and then another three under normal conditions on site. One challenge was to avoid the appearance of the cobbles seeming to float in a sea of mortar, like icebergs. It was during these tests that it was decided to fix the new cobbles vertically, so that only their tips were visible. A proprietary non-cement mortar was used because it is stronger than ordinary Portland cement and does not leave stains. It can also be washed off during the curing process.

REINSTATING THE SURFACE

|

|

| Section showing the construction specification |

Areas of square setts, laid out as smooth walking surfaces across the cobbles, were easier to re-install. They too were bedded into the non-cement base and were also pointed up with the same material. The original layout also included a series of granite sett drainage channels across the cobbled area. In practice, as the cobbles were originally laid in and on hoggin, surface water percolated through it so that the drainage channels were more decorative than functional. With the introduction of a new solid inflexible base, surface water needed to be correctly channelled so the setts were pointed flush with the tops of the setts. Care was taken to lay them out accurately, even though the setts were not all exactly the same size. The three-row drainage channels, for example, were set out with the aid of a string line so that the outer edges of the setts were in a reasonably straight line. Any variations in sett size were accommodated at the inner edges.

Accessibility for wheelchair users was considered carefully from the outset. Fortunately, the original design of the square included a path of continuous smooth York stone paving at the outer edge and also around the perimeter fence of the circular garden.

Admittedly, walking on the round cobbles is not particularly easy; but then it never had been. As there is a smooth access surface in all directions, people who prefer not to walk on the cobbles are not obliged to. The result is very satisfactory and a measure of its visual appeal is its ongoing popularity as a shooting location for television productions, both period and contemporary.

VALUABLE LESSONS FOR OTHER HISTORIC STREETS

The most common street-level conservation work involves footway reinstatement. The problem of broken slabs occurs frequently. In almost every case, the damage is caused by vehicles mounting the footway and damaging the paving. The damage typically occurs because the slabs were originally laid without sufficient support or have been lifted and relaid without sufficient support during the digging of a service trench. Because service pipes and cables are laid directly below pavements, paving slabs are constantly being lifted and re-laid. Some authorities count their service openings in the thousands per year. This is the reason why odd broken slabs are so often seen next to inspection covers or along the line of a service trench.

|

|

| The Radcliffe Camera, Oxford with new cobbles in the foreground |

The solution is to ensure that a non-compactable fill is used to close service trenches. Otherwise the trench will sink as the fill material gradually compacts. The support for the paving material is eroded and as soon as any heavy load is applied, the paving slabs break.

In the carriageway, setted surfaces often fail where they form part of or are adjacent to a flexible surface. Most blacktop surfaces are sufficiently resilient to withstand some movement caused by heavy vehicles. Because the setts themselves are completely solid and cannot flex, the pointing of setts is put under strain. The slightest movement causes a very small crack, which allows moisture to enter. The moisture freezes and expands in winter, the crack opens up and eventually the setts are forced out by the movement of traffic.

Areas of setts at bus pull-ins are very vulnerable. As each bus turns its front wheels to leave the pull-in, the same small group of setts is put under sideways pressure, sometimes dozens of times per day. Repairs on such areas should ensure that the pointing between the setts is as strong as the setts themselves so that the lateral forces are transferred from one sett to the next and eventually to the base.

Historic road and footway surfaces can be conserved and reinstated but they need to be either protected from modern heavy vehicles or reconstructed to withstand them. This means uniting engineering skills with an awareness of local character and sound urban design; in short, urban engineering.