Retail Detail - Shopfront Designs

Shopfronts range from hideous examples of commercialism to exquisite examples of contemporary design. Jonathan Taylor outlines their historic development and the importance of good detailing.

The origins of the traditional shopfront lie in the market stalls of the Middle Ages. Prior to the industrial revolution and the vast urban development which accompanied it, retail trade was dominated by the market. The earliest shops were generally simple variations of the market stall, and only partly enclosed by the building. An awning over a projecting stall was common. In another variation, the opening was protected by two horizontal shutters; the top one folding up to double as an awning or 'pet roof', and the lower one folding down to form the stall board. Today the term 'stall-riser' is still used to describe the front of the shopfront below the window.

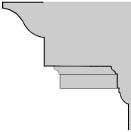

|

| Figure 1. Elevation showing elements of late 18th and early 19th century shopfronts. Note the entablatures, consisting of cornice, frieze and architrave. The frieze is enlarged to carry the sign-written name of the shop. The entablature is supported on the pilasters by capitals or console brackets. |

By the mid 18th century, the shop as we know it today had emerged. Glazing, which had probably first appeared in the late 17th century was now common. Small paned windows, frequently projecting out from under a canopy appeared in the more prestigious retail areas of London and the principal market towns. Hanging signs were also introduced at an early stage, growing larger as each competed for attention until they were banned in the City of London in 1764. By 1784, shopkeepers were sufficiently numerous to be targeted for taxation, as William Pitt struggled to raise funds in a period of continuous conflict with France.

In the spirit of classicism which then prevailed, a language of ornamentation emerged which was unique to the shopfront. Classical detailing was introduced to relieve the appearance of large shopfront openings in the walls of ordinary urban terraced houses. The beam or 'bressummer' which supported the facade above was disguised by an 'entablature', and classical columns, pediments or scrolled corbel brackets were introduced to give visual support. The entablature provided an ideal opportunity for displaying the name of the shop, and the frieze or fascia was enlarged accordingly.

Early Georgian shopfronts are relatively rare, but isolated examples can be found in many towns and cities throughout the UK. These are typified by the paired, bow-fronted oriel windows on either side of a central, half glazed door, which were popular from the mid 1740s to the end of the Regency period. However the Georgian period was equally responsible for a wide variety of other designs, covering the whole spectrum of popular taste, from the cool classicism of the Greek Revival, to the pointed arch glazing pattern of the 'Gothick'. Shopfronts designed to display state-of-the-art produce were often required to be of the latest design, and their forms reflect the fashions of the period. Many interesting designs were consequently destroyed with every change of ownership.

|

VICTORIAN DEVELOPMENTS

The huge urban expansion which occurred in the Victorian period resulted in a proliferation of retail developments in every town, city and suburb. Manufacturers such as I and J Taylor and SW Francis and Co offered wide ranges of standard designs which could be selected from catalogues. Typical examples included tall shop windows, frequently incorporating a decorative cast iron ventilator underneath the timber or glass covered fascia. Sunblinds were often incorporated in the cornice and timber roller security shutter were introduced towards the end of the century replacing detachable timber shutters. At the base of the window the timber frame included both a bottom rail and a deep sill - a detail frequently

| Traditional and historic timber shopfronts in York |

overlooked by modern interpretations. Panelling of the door and stall-riser was usually raised and fielded.

| |

|

||

| 2. | Typical glazing bar profiles for shop windows | 4a. | Section through a shop front door showing the reveal for a shutter |

|

|

||

| 3. | Typical shop cornice profiles | 4b. | Section through a typical sill detail |

Although machine-produced plate glass was available from around the turn of the century, its use in shopfronts was quite rare until the 1840s when tall panes unbroken by horizontal glazing bars began to appear in increasing numbers. The production of larger sheets was limited more by cost than by the technology available. Isolated examples of full size plate glass appear in shops such as Asprey's on Bond Street, London in the 1860s, becoming increasingly common towards the end of the century.

The variety of designs increased rapidly throughout the period, with the early appearance of cast iron, followed by brass- and bronze-clad timber around the middle of the century, with fine detailing often incorporating a stone or marble stall-riser without a sill.

CONSERVATION

Today local authorities are becoming increasingly concerned by the disastrous effect that the appearance of modern shopfronts and signage have had on our town centres, and are imposing tight controls on new designs. Most of the more important shopping streets lie within conservation areas, and the local authority will usually require conservation area consent for alterations to original shopfronts.

Older examples should be conserved if at all possible. All original components have an historic value which cannot be replicated, comparable with the finest antique. A suitable replacement for some components, including glass and metalwork in particular, may not easily be found.

Often, apparently new shopfronts may contain sufficient numbers of the original details to enable accurate restoration of the original. New fascias may hide the original cornice and the upper part of the window head. In such cases restoration inevitably results in a substantially more impressive design than can be achieved with a standard modern replacement.

Where no original designs have survived, a modern solution will be the most honest approach, but a high quality, traditionally detailed design may also be appropriate, and often preferred. In both cases the quality of detail is crucial to the success of the design. Crude, square mouldings and planted mouldings are now common, often applied without any real understanding of the way a frame is constructed. Secondary fascias are often incorporated, disrupting the rhythm of tall shop windows along the street, and the concrete floor slab is often exposed. Prior to the arrival of the aluminium systems, shopfronts were almost always designed to fill the opening, from the pavement to the underside of the fascia, usually with a rendered or timber skirting, scribed to the pavement.