Sourcing Stone for Building Conservation

Terry Hughes

|

|

| Stone contributes to landscape character and detail through the scenery and the buildings. The very successful Barns and Walls Conservation Scheme in Swaledale has supported a small quarry within the National Park. The support of the Yorkshire Dales National Park authority has demonstrated that small scale quarrying can conserve their built heritage without damaging nature conservation. (Photo: Terry Hughes) |

There can be few people working in building conservation who haven't faced problems trying to find the appropriate stone for repairs. The decline of stone quarrying in the 20th century created difficulties enough, but in recent times the use of old quarries for brownfield developments and for landfill has sterilised many important sources of stone. On top of this, closed quarries have been adopted for recreational purposes such as country parks, and have been either specifically designated for nature conservation or have fallen within large environmentally protected areas such a SSSIs, National Parks or Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The upshot has been that it is very difficult or even impossible to obtain even very small quantities of some stones.

The realisation that the appropriate conservation of historic stone buildings was becoming impossible prompted English Heritage to ask the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister to commission the Symonds Group (now Capita Symonds) to carry out a review of the supply of building and roofing stone in England and Wales, and this was published in 2004 as the Symonds Report.(1) This document made many recommendations for changes in the way mineral planning is organised. It recognised that there was a gap in our knowledge of building stone generally and, more specifically, what stones had been used in the past and which buildings they had been used in. To help overcome the latter problem, it suggested the creation of a stone database. Simply recording the stones of major importance used in the most prominent buildings would be a major undertaking. If it were to take into account all the stones used for vernacular buildings as well (as it should), the task would be daunting indeed. Nonetheless, English Heritage is embarking on a four-year programme to try to achieve at least a major part of this.

The other outcome of the Symonds Group's recommendations has been a review of minerals planning, the results of which will be published later this year as Mineral Planning Statement 1 (MPS1). This is expected to place responsibilities on mineral planners and English Heritage which will principally be focussed around the concept of safeguarding sources of building and roofing stone. In broad terms, MPS1 will state that:

|

|

| Damage to the historic fabric caused by repair with a lower porosity stone. This increases moisture movement through the surrounding stone leading to its deterioration. (Photo: BGS © NERC) |

- regional planning boards should set out policies for the safeguarding of nationally, regionally and locally significant building stone resources English Heritage and the stone industry are encouraged to make mineral planning authorities aware of important sources of building and roofing stone that they consider should be safeguarded local planning authorities should notify English Heritage and English Nature when a development proposal is made which affects an old building stone source to provide an opportunity for its significance to be assessed; and

- mineral planning authorities should identify quarries of importance to the built heritage in development documents, whether the quarries are disused or active, and describe the approach to be taken to these in terms of minerals and other planning applications.

Clearly, to carry out these duties there is a need to know what stones have been used, where they came from and which buildings they went into. In practical terms there seem to be two ways in which this could be done: reacting to events, such as development proposals which affect old quarries or their immediate vicinity, or compiling the database. Taking the first approach it is hoped that there will not be so many proposals that English Heritage is completely swamped with enquiries from mineral planners. But, given a reasonable level, they should be able to respond by carrying out a specific review of the site's significance. This would include establishing whether there is likely to be any suitable stone left in the quarry or nearby.

Taking the second approach, creating the stone database, English Heritage has already started to investigate how this might be carried out and this work will continue through to 2007. The investigation is currently looking at a number of approaches and more may be included later. They fall into two groups: assembling existing data into an accessible form and commissioning new research.

Although it can be very difficult to get at, there is a great deal of information about historic stone usage and this part of the study is looking at two sources. A proposal is being developed to transcribe all the quarry locations in the Ordnance Survey maps, starting from the original editions, and all the data in the British Geological Survey's Mineral Statistics into a database which would be available online as a graphical information system (GIS). This is a costly exercise and is dependent on funding being available.

The other important collection of stone usage records is in the work done by individuals and local interest groups. These include regional and town guides to stone buildings, as well as more comprehensive county-wide building stone studies carried out by geological societies. Much of this is unpublished and sitting on individuals' bookshelves. It is hoped that the societies can be persuaded (with some funding) to assemble their knowledge into a consistent format that would eventually be published as an atlas of English building stones. Several geological societies have already expressed their willingness to help.

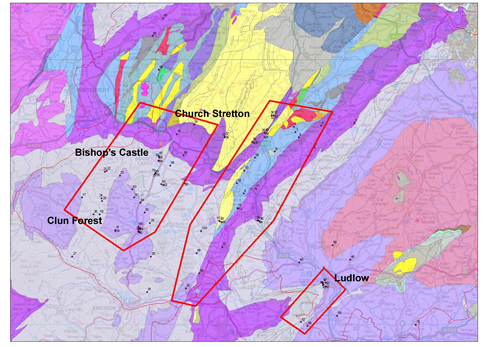

|

| The distribution of roofing stones was studied in South Shropshire. The stones which have been used include; to the west, the Cefn Eynion and Clun Forest Formations; centrally along the A49, the Soudley and Chatwall sandstones; and, at Ludlow, the Tilestones (Murchison). (Credit Terry Hughes. Mapping by BGS © NERC) |

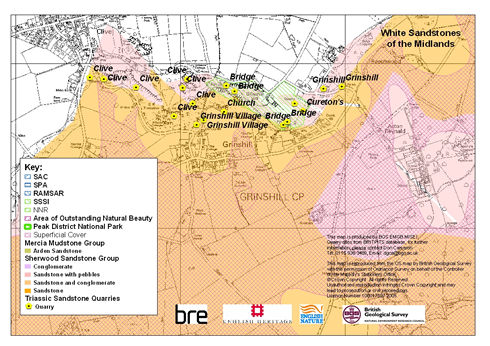

|

| The White sandstones study reviewed sources of Grinshill, Arden and Bromsgrove sandstones. Locations of historic and modern quarries at Grinshill in Shropshire. (Credit BGS © NERC) |

Geological societies' expertise could also be utilised to carry out new research. This approach was trialled in 2005 in south Shropshire, where English Heritage funded the expenses of the volunteer workers and a co-ordinator, Andrew Jenkinson, to research the use of stone slates in the area. Most roofs over 400 square miles were viewed at least from a distance to locate the stone ones and a total of 100 were identified and described - an additional 45 beyond the 55 that were listed. Many of the geological stone types were identified and some historic quarries and potential locations for small delphs identified. Altogether the study was very successful and it was achieved at a modest cost.

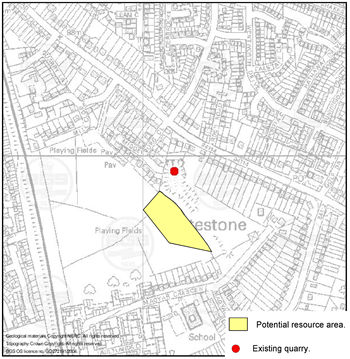

Another trial study was carried out by the British Geological Survey (led by Graham Lott), the Building Research Establishment (leader Tim Yates) and English Heritage's stone consultant (David Jefferson). It covered the white sandstones of the West Midlands: the Grinshill, Arden and Bromsgrove sandstones. The study looked at the existing and closed quarries, the current need for stone for repair and the supply situation, the potential to re-establish production where none existed and the constraints on this. To assess the need for stone, a detailed field study of buildings in each region was carried out which identified the stones used and assessed their durability. The reports generated by these two studies will be published in 2007.

It also became apparent during the white sandstone survey that in some projects serious difficulties had been experienced in selecting an appropriate stone for repairs, and that decisions seem to have been made primarily on the basis of appearance. This had led to problems resulting in deterioration of the surrounding fabric. This issue has been recognised for some time and, partly in response to this, English Heritage has published a technical advice note, Identifying and Sourcing Stone for Historic Building Repair.(2) Along with advice on the practicalities of identifying and finding appropriate stone, the booklet includes detailed guidance on the technical criteria which should be applied in making a choice. These include petrography, chemical characteristics, appearance, geological age, porosity and compressive strength. This, of course, raises another issue when carrying out repairs: is it really necessary to use the same stone as the original? There may well be a number of reasons for choosing a different stone - the original may be entirely unsuitable or completely unavailable - but in either case an informed decision is only going to be possible if information is available on alternatives. Which brings us back to the need for the database.

|

|

| In the White sandstones study the potential for reestablishing production was assessed at a number of old quarries. The potential working area is shown in yellow. (Credit: David Jefferson) |

So looking to the future, when we have the comprehensive database or something approaching it, we will be in a position to safeguard stone sources, but this will inevitably raise the question: which stones are the most important? Or is this stone more important than that one and more deserving of safeguarding? In this situation there will be a need for some means of ranking the importance of stones - something along the lines of listing grades - and perhaps a designation of grades of 'heritage quarries'. This would also provide a facility for balancing the importance of the value of the built heritage and nature heritage value of a quarry or stone source. Towards this end the following is a first attempt at articulating the relative value of individual stones. It is conceivable that this system could be quantified for each criterion and a numerical score generated for a quarry. Comments on this would be welcome (see below).

RELATIVE VALUE OF STONES

Extrinsic value is the property we would normally apply to a particular stone almost without thinking. It is the size of the market: the extent to which a stone has been used in the past and will be needed in the future for building repair. This is also the value which the commercial stone industry would use. The greater the demand for repair and new build the more valuable the stone is and the more economically viable any quarry would be. The intrinsic value of a stone is determined by its technical suitability and its cultural and heritage importance. The former is not necessarily directly related to its past extent of use although this will certainly be the case for some stones. A number of attributes could be used to assess the intrinsic value of a particular stone.

Building importance One way to articulate the importance of a stone would be in relation to a concept with which we are all familiar: the listing grade (or national/historic monument designation) of buildings in which it has been used. The presumption being that, provided all technical criteria were satisfied, the higher the grade of the building the more important it would be to use an authentic stone for repairs. This provides one parameter against which a stone could be ranked in importance. A simple count and scoring for each building and its grade could produce a numerical score for a stone.

Technical importance This may be defined as the extent to which its properties are special in terms of its suitability of use: strength, porosity, etc, and its compatibility with the surrounding fabric. Recent experience indicates that compatibility has a much greater importance than has been realised in the past. For some stones and some applications it may well prove to be the primary factor in selecting a stone for repair. It is probable that in many cases the most suitable stone on these grounds will be the original material from a closely defined location - a particular horizon in a particular quarry for example.

Cultural importance A stone may have a high cultural value even if it has only been used in one or a small number of buildings. If these are of great architectural or historic value, there would be a strong case for repairing them with the original stone. Similarly, a stone which has been used for all the buildings within a village is essential to its sense of place and should be used to repair the buildings. However, cultural importance is largely unquantifiable because it reflects abstract concepts such as a sense of history, historical references to persons or former industrial, agricultural or cultural activities; one's place in society; local or regional building diversity and the importance of the 'particular'; of beauty and eccentricity.

Distinctive appearance Conservation planning guidance focuses on the appearance of buildings. The distinctiveness of particular stones will therefore be a fundamental aspect of their relative importance. Stones should be assessed against surface texture, colour, bed thickness and other dimensions for masonry or size range and thickness for roofing, etc. The weathered appearance, which will be determined by the mineralogy as well as external factors, and the plants which grow on the stones are also critical to determining whether a particular stone should be used for repair.

Local distinctiveness The diversity of stone types used in an area impacts on its distinctiveness. Typically it will vary from village to village. This characteristic will be predominantly based on early transport systems, mainly horse-drawn but also involving waterborne transport.

Regional character and continuity Different stone types will often be similar in character creating a coherent style in a (geological) region. Within the region there could be an element of substitution over time as quarries opened and closed and transport systems developed.

Thematic use Landowners or industrialists often used stone from their own land holdings in preference to those with a lower transport cost. This is expressed in suites of buildings, including model farms and estate villages for example, all constructed from the same stone.

Landscape character Buildings in the open landscape such as field walls, animal shelters, hay barns, sheep pens, shepherds' shelters and buildings associated with the seasonal movement of livestock, were inevitably built of stone obtained from the immediate vicinity. Because all these buildings are a product of the local farming system which in itself is largely a product of the natural zone in which it operated - the soil, climate, elevation, etc - they are intimately linked to the natural environment.

Detail Many non-building uses of stone are important features of village and town-scapes. Milestones, stiles, bollards, gravestones, river and canal banks, kerbs, copings, pavements and other flagging, steps and gate posts; their texture, shape and style are distinctive and local. They are the details which add character to their locality.

Feedback Comments on how the relative value of individual stones should be assessed would be welcome. Please contact either Chris Wood at English Heritage (chris.wood@english-heritage.org.uk) or the author (terry@slateroof.co.uk).

~~~

Notes

(1) A Thompson et al, Symonds Group Ltd, Planning for the Supply of Natural Building and Roofing Stone in England and Wales, Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, London, 2004

(2) The English Heritage Technical Advice Note Identifying and Sourcing Stone for Historic Building Repair is available free from English Heritage Customer Services Department, PO Box 569, Swindon SN2 2YP.