Teatime and Toilets

Jonathan Taylor

|

||

| New toilets designed by Conservation PD for St Mary’s, Hornsey Rise, London (above and below), in what was the north aisle. |

Historic churches and chapels which remain in use are community meeting places. Those meetings may be for the primary purpose of worship or, as is the case of a growing number of places of worship, for a variety of other community events too. In either case, serving refreshments may be desirable but providing toilet facilities should be considered essential, whether for those attending a wedding, a concert or an ordinary Sunday service. For the elderly and the less able, the lack of toilets nearby can make a visit to their church an uncomfortable venture. Parents with small children may also be discouraged from attending a long church service where there are no loos.

Why then do not all places of worship have the appropriate facilities? The reality is that most historic churches predate the introduction of the modern flushing WC, often by hundreds of years. Today, unless there is a dedicated church hall nearby, introducing the facilities we need usually poses two challenges. Firstly, there is the question of design: where do we place the facilities in a way that is relatively discreet and does least harm to the character and significance of historic fabric? And secondly how do you install the necessary drainage or septic tank? Many places of worship are surrounded by burial grounds, and excavating a trench for the services required might disturb buried remains and any archaeological evidence associated with the site. Such problems are rarely intractable, but both issues have to be approached carefully.

DESIGN ISSUES

|

||

| The toilets are screened from the nave by the full height partition in the left arch. (It had previously been partially infilled like the arch to the right.) The entrance is the door on the left. (Photos: Eleni Makri, Conservation PD) |

The least invasive solutions are often the most compromised, but sometimes they work very well. At their simplest, facilities for making and serving teas, washing up the cups afterwards and storing the crockery can all be accommodated within a single large cupboard. If neatly designed to reflect the construction and detailing of pews or other furnishings, even a couple of large cupboards can have minimal impact on the character of the interior.

The provision of a small kitchen sink or a toilet will depend on there being both a water supply and a drainage system, or on the practicalities of introducing the services required. Where there is neither, some rural churches have introduced small composting toilets in the grounds of the church. Also known as ‘dry earth closets’, these are among the least invasive solutions, with no connection to either mains drains or a septic tank. In Canada these are commonly found in national and provincial parks, but they are rare in the UK, and on a warm summer day the smell can be off-putting. However, they are environmentally sound and safe to use.

The introduction of mains drainage or a septic tank allows toilet facilities to be located indoors, which in bad weather is clearly preferable. However, finding space for a small room will inevitably effect a significant change in the character of part of the interior. Every church is unique, and a solution that is suitable in one place may be unsuitable in another, but the following points may be helpful.

Continuity of use: Conservation is said to be the process of managing change in ways that best sustain the heritage values of the place for present and future generations. As such, conservation is often a balancing act, with gains in one aspect of a building’s significance weighed against drawbacks in another. Seen objectively, proposals aimed to ensure the continued use of a place of worship are among the most important, because religious use is intrinsic to its character and significance. Some degree of alteration is acceptable in even the most important buildings, particularly if introduced in a way that is reversible.

|

|

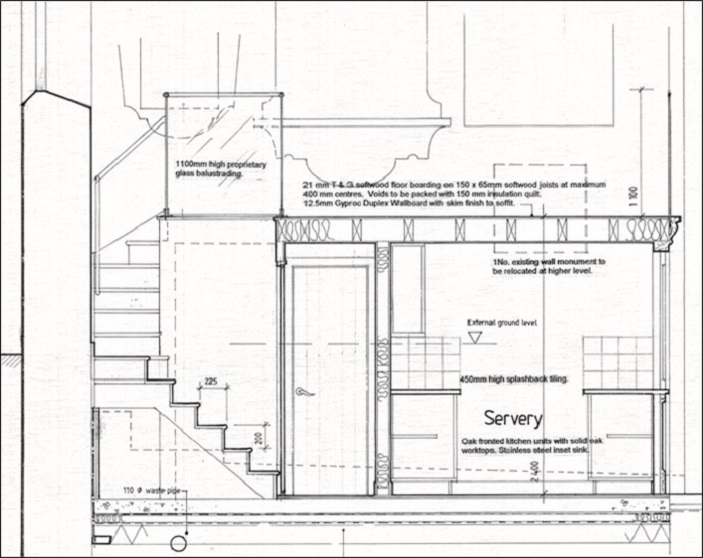

| A traditionally detailed tea servery and toilet infill to the base of a bell tower at St Wilfred’s, Leeds, by Richard Crooks Partnership: the platform above includes a place for bell ringing as well as a font. (Photo and drawings: Richard Crooks) | |

|

Reversibility: Toilets and kitchen facilities are often designed as pod-like additions which are, in theory, easily reversible, allowing the form and shape of the building to be recovered at some future point, or for a better solution to be achieved. To be fully reversible, no part of the scheme should have any permanent effect on the existing fabric, but in practice the addition of services almost always requires some degree of physical alteration, as does the attachment of new structures such as door frames and partitions. As ever in conservation, it is important not to lose a sense of perspective and to weigh all the issues. If a location is perfectly suited to the use proposed and there are no alternatives, designing for reversibility could be academic as, once installed, it will never be removed. In this case the best solution may well be one that complements the space and inflicts the minimum intervention on historic fabric, irrespective of whether it is reversible.

Minimum intervention: One of the mantras of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings has always been to fit new to old, retaining as much of the original fabric as possible without alteration. This philosophy applies to all aspects of conservation, taking into account how the new work will impact all aspects of the significance of the existing building, its fabric and its setting.

Long term performance: The effects of alterations need to be considered in terms of both their immediate impact and their effects over the longer term to avoid any unintended consequences. For example, anything that covers historic fabric, be it paint, rubber-backed carpet or a dry lining over areas of wall, floor or monument, must be considered in terms of vapour permeability. Covering large areas with less permeable materials may set up a chain of events that leads to saturation and heat loss in one area, with evaporation and salt efflorescence at the extremities. Trapped moisture may also cause new and original fabric to decay.

Honesty of design: For a small church or chapel where the facilities need to be located on site, a toilet capable of catering for less able bodied and elderly people is a significant structure. If there are no rooms or small spaces that are suitable for tucking the facilities into, a bold and honest solution is usually best. A structure which is not in keeping with the scale and quality of its surroundings will stand out, even though it is smaller and less consequential.

Stylistically, design options may be considered in three categories:

• Pastiche, where existing or historic design approaches are copied

• Traditional, where existing or historic design approaches are echoed but not copied

• Distinct, where a very different style is chosen.

|

||

| Drainage trench at St Oswald’s Oswestry: the shallow excavation over previously disturbed land enabled

the use of a mechanical digger, albeit under an archaeological watching brief. (Photo: Timothy Malim, SLR Consulting) |

Where the pastiche approach might lead to modern fabric being mistaken as the original, this approach can confuse the history of the building and its appreciation. However, apart from this one caveat, all three approaches are appropriate in different circumstances. In the context of a church, it may not be possible for the new structure to blend in, and a distinct stylistic approach which recognises that the new structure really is different, can sometimes be the only viable option.

HERITAGE CONSENTS

Most places of worship are exempt from ordinary listed building consent requirements under the Ecclesiastical Exemption, but all alterations, inside or outside, will need the permission (or a faculty, as it is sometimes called) of the church body concerned, whether listed or not. The process is not dissimilar from the secular planning process and the views of the local authority and the national heritage bodies are sought.

In addition, planning permission would be required from the local authority for any works classed as ‘development’ such as an extension or the construction of a free-standing toilet in the grounds. When considering approval, the local authority will take into account the impact of the development on the listed building and its significance.

In some cases church building and churchyard structures are also scheduled monuments, which are not covered by the exemption. In this case, if a scheduled monument is affected in any way, the permission of the national statutory authority would also be required (either Cadw, Historic England, the Historic Environment Division of NI or Historic Environment Scotland).

|

||

| A composting toilet in a churchyard at Stondon, Bedfordshire. (Photo: Emma Critchley, Diocese of St Albans) |

EXCAVATIONS FOR SERVICES

The trench excavations required for running the water supply and laying the drains are usually less than 1.8 metres deep, which is the depth at which burials are likely to be encountered. However, in sites where religion has been practiced for centuries or even millennia, there may be a significant risk of the excavation uncovering archaeological material, and there may also be fragments of human remains in the top 1.8 metres of earth and clay of older churchyards. It is therefore best to engage the advice of an archaeologist at an early stage to identify the most suitable route to take through the site, and to advise on the application itself. An archaeological assessment may also help to establish the best location for the facilities, avoiding mistakes later.

When applying for permission, the application should include an assessment of the likely impact of the proposal on burials and archaeology, together with a statement outlining how the excavation work is to be carried out. This would usually involve hand-excavation of the trench by the contractors under the supervision of an archaeologist, but machine excavation may be possible in areas of low risk. The archaeologist would then monitor the work and record anything of interest. Usually this would proceed quite quickly and with minimal delay, provided that the trench is relatively shallow.

COMMUNITY

The introduction of good facilities for the congregation, the community and church visitors may pose complex issues of design and heritage as well as practical problems, but these developments should be considered essential in the 21st century. The key is to consult carefully and engage with all stakeholders. If the approach is well managed it can itself bring together the community and help in unlocking funding, assistance, and good will, securing the future of the building as a community hub and an asset.