Dramatic Plasterwork

Fibrous Plaster in Theatres

David Harrison

|

|

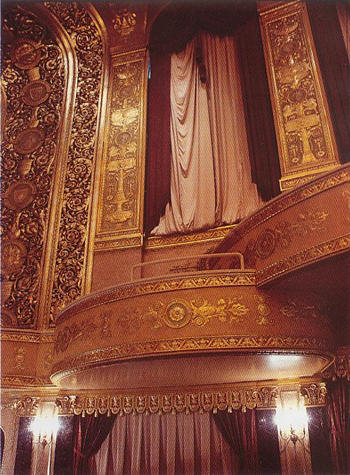

| The Stanley Warner Theatre in Washington DC, fully restored using a mix of fibrous plaster casts and consolidation, and solid plastering to new loge boxes. |

The term 'fibrous plaster' is usually used to describe a thin lightweight modular construction composed of hessian (or 'jute scrimcloth' as it is also known) soaked in gypsum plaster and cast in a mould. It is strengthened by sawn timber laths and ribs which are also used for fixing and support. The technique superseded solid lime and gypsum plaster for fine decoration in the late 19th century and is the principal form used today for cornices and other fine decorative work.

THE ORIGINS OF FIBROUS PLASTER

The various forms of plasterwork, from hand modelled stucco to glass reinforced gypsum may all contain some kind of fibre for strength, and most lime mortar ceiling work contains enough animal hair to bind the plaster together between the lath, contributing to its flexible strength and thus its characteristic longevity. However, most lime plaster is run or spread in situ, and enrichments which may be added are usually small solid casts stuck to the background with a 'slip' of mortar, rather than cast in large sections. This is the type of work usually referred to in the trade as 'solid'.

The technique of reinforcing gypsum plaster with hessian or canvas has been known and used for thousands of years, and probably predates the Pharaohs. Millar, writing in 1897 (see Recommended Reading), mentions mummers' masks found in Kahun dating from 4,500 years ago. However, modern fibrous plasterwork in England can be said to date from Leonard Alexander Desachy's patent of 1856, which drew on a Parisian recipe.

Fibrous plaster has a number of key advantages over solid plaster and proved immediately popular. Fibrous plaster weighs much less and is better reinforced so mouldings can be prepared in a studio or on site, prior to installation, avoiding the need to run mouldings in situ. The use of modular cast mouldings can allow great variety of ornament applied in a bespoke way. For example, incorporating a stock cherub into a dome made to specific dimensions saves having to model each cherub from scratch. The result was cheaper decoration and more of it. Fine plasterwork could now be afforded by more people, and those who could afford it could afford more of it.

Not only houses benefited, but also theatres, music halls and other settings where a grand effect was required with perhaps a limited budget and minimum take-up of space. Most theatres have accessways behind the facades and lighting rigs cut through ceilings, and in solid work their lavishly ornamented plasterwork would weigh so much as to require major structural support, decreasing the useful space behind.

Speed of operation on site is another advantage in a theatre. Normally, the decision making processes - the financing, the architectural and interior design, and the procurement take so long that the time left for execution of the project is cramped.

In the past hundred years, fibrous plaster has come into its own, as increasingly flexible moulding compounds have made it possible to produce casts with fine sharp relief, undercut decoration, piercing and inlays, and modern plasters have increased strength and lightness.

CONSERVATION IN THEATRE

The largest single demand for fibrous conservation today is in theatres, partly because all theatres, ancient and modern, require that a ceiling safety licence be granted by the local building office every five years. As the limited funds available to theatres tend to be concentrated on production rather than building maintenance, the licence is often the only spur to looking after some very fine craftsmanship.

Most theatres will contain a broad mix of building materials and techniques collected from each era through which they have passed. Fibrous plaster has been common for the past 140 years, and as the normal life of hessian scrint is about 80 years, most old theatres require some careful treatment to preserve their fibrous plasterwork. The structure of a fibrous panel, being more than half composed of organic material and attached to timber struts, leaves it highly vulnerable to attack by moisture and all forms of cellulose-eating moulds and fungi. Once dry rot for example has taken hold, it can travel through the fabric of a theatre very quickly. The most important part of fibrous conservation is therefore prevention.

| Simple measures for prevention: |

| Regular inspection, particularly in difficult to reach areas: Debris tends to accumulate on the upper surfaces of ceilings within the void above. This space should be cleaned out to allow easy access and to allow the structure to be readily monitored and maintained, as well as to reduce fire risk and to keep the weight of debris down. Fall arrest systems and walkways are essential for safe regular access to roof spaces and voids and usually their development will need be given a higher priority as they fall far from the top of most theatres' budget list. |

| Ventilation: Often ceilings are insulated from behind, cutting heating bills, but any reduction in the airflow across this space also prevents the natural drying out of any damp which accumulates from condensation in particular, encouraging infestation. Difficult corners should be specifically ventilated. |

| Roof repair: The roof of a theatre is usually the last place that money is spent, despite being the most obvious source of water penetration. If left for long enough, a slipped tile or a blocked gutter can lead to rampant dry rot, costing millions of pounds to rectify. Again, a program of regular inspection and maintenance is essential. |

| Liaison with technical crews of visiting shows: A clear brief is required explaining what is and is not permissible regarding the fabric of the theatre. Probably half of all damage to fibrous work in theatres is caused by crews rigging new shows. For example, the bigger shows these days often require all manner of drapes, light rigs, walkways and even people to hang out over the audience. It is a sad fact that the original suspension points are often obscured by debris, and makeshift ones are cut by visiting crews whose main thought is for the setting rather than the venerable fabric of the theatre. At the Royal Opera House recently, a complete set of suspension points with carefully designed floral covers was found during conservation which had been forgotten for years. |

CONSERVATION AND CONSOLIDATION

If the prevention approach has not worked or has been followed at all, then conservation must take the form of consolidation. However, before any work is carried out, moulds must be taken of any area likely to be damaged in the preservation process, including any section showing rot, mould, water damage or crew vandalism for example.

To make a mould, the area concerned needs to be cleaned back and front, and temporarily supported if necessary. There are a number of paste-on moulding compounds available, with adjustable setting times and hardness. A layer of the compound is applied and allowed to set. This flexible layer is then backed with plaster and a framework to ensure that the geometry of the mould is retained. The plaster back is then removed and the flexible mould peeled off. This can be used to cast a new section of fibrous plaster later for cutting into the original.

Conservation of the existing fabric, assuming that the scrim is still intact, consists of ensuring that the supports and ties are intact. These will be either wire wrapped in Hessian/plaster wads, or sometimes, direct fixings to the framework.

Where the integrity of the scrim and the fibrous panel itself has been lost, it is sometimes possible to strengthen it by carefully cleaning the back of the plaster, applying a consolidant such as Primal, and sticking a reinforcing layer of hessian over the weak area with casting plaster. The design of a patch repair such as this should take into account the need to incorporate any existing timber support, and often additional support will be required - galvanise or stainless steel sections are often used to avoid any repetition of mould infestation. Wires and other fixings can be attached to the strengthened section. Existing ties can be assisted by cleaning off failed plaster and re-wadding, or by re-attaching the ceiling end of the tie to its support.

Where large sections of original plasterwork have been lost or cannot be repaired, glass reinforced gypsum is often used as a substitute for the original material, chiefly because glass fibre is not affected by decay to the extent that hessian is. This material is the direct descendant of Desachy's imported patent, widely used in modern buildings in much the same manner.

At the Regent Theatre, Hanley, for example, a mixture of the above consolidation and repair techniques has been used, but with modern sprayed glass fibre-reinforced gypsum replacements for the proscenium arch, which was too badly decayed to keep.

A wonderful example of theatre conservation is the work being done at present by Mervin Stokes, David Wilmore and their team at the Gaiety Theatre, Douglas, Isle of Man.

This masterpiece of Frank Matcham, opened in 1900, has almost been brought back to its original condition. Careful conservation of water damaged fibrous plasterwork gilding and paint finishes has given a new lease of life to one of the most complete and original remaining examples of the work of this prolific classicist. His robust fibrous plaster casts of classical beauties and cheeky cherubs, together with his flair for the most modern (turn of the last century) traps and other stage mechanisms, and his sense of sightline and comfort mixed with architectural delight provide fresh impetus, if any were needed, to the plaster conservator.Here is work which demands to be conserved, not simply out of respect for the past, but to keep an original masterwork working and providing the pleasure it was designed to give.

An earlier example is the scheme completed in 1858 at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (1732), where a wonderful mix of materials was used to restore the interior following damage by fire in 1856. Traditional solid lime and gypsum plaster on lath in the corridors and hand-modelled work in the Royal Box contrast with Desachy's newly reinvented fibrous plasterwork in the balcony fronts and slips. Traditional carton pierre or papier ri (paper mashed up with glue and set in a mould by 1858 a century-old technique) was used in the enrichments to the vaults, while the German inventor Frederick Bielfeld was commissioned to use his new pressed oil-impregnated fibreboard in the great dome. This material, which is adorned with plaster enrichment, was rolled and pressed into shape on formers, oven baked and fixed in panels to a timber background. Bielfeld's board has proved to be a very durable material.

At the Royal Opera House today we now have some fibreglass lighting hatches in the same highly enriched dome. This modern material has enabled a functional improvement to be made in keeping with the appearance of the original design.

LOOKING AHEAD

The development of fibrous plaster enabled the mass-production of highly elaborate decorative elements such as cornices and ceiling roses which play such a vital role in Victorian and Edwardian interior design. The chief threats are neglect, accidental damage and damp and decay - particularly of the hessian backing. To be successful, the conservation of fibrous plaster needs to look at the problems encountered holistically, within the widest context of the existing environment. The true aim of conservators must be to conserve the skills of the craftsman, so that the continuing development of each trade can inform the preservation of its own history.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- J Ashurst and N Ashurst, Practical Building Conservation Vol 3: Plasters, Mortars and Renders, Gower Technical Press, Aldershot, 1988

- W Millar, Plastering, Plain and Decorative, 1897, Donhead, Shaftesbury, 1998

- J Ashurst, Mortars, Plasters and Renders in Conservation, EASA, London, 1983

- SPAB pamphlets on plaster and its repair, Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings