Timber Carving

This article provides a useful introduction to the principal causes of deterioration likely to be encountered in the conservation of historic carvings in wood, excluding those which affect their finishes

David Luard

In pre-Restoration Britain historic carvings were usually carried out in oak, an indigenous hardwood. This was not because oak is the perfect medium - it is not - but the wood was readily available, and most early carving was applied to functional elements of buildings. Only later did it become a decorative element in its own right. The addition of carving was a way of embellishing an otherwise plain wooden surface.

By the 17th century carving had assumed an importance of its own and in many instances was purely decorative. Lime was introduced and championed by Grinling Gibbons in the 1670s and it soon overtook oak in the field of internal decorative carving. These two woods formed the basis for the internal carved medium.

The third important type of wood for carving is softwood, particularly pine. Softwood had assumed a greater importance as panelling came within the financial reach of a greater number of people. Cheaper than oak, it could be painted or grained to look like the more expensive material. But it was not always painted, and there are instances of very high quality work being carried out in softwood that was always meant to be exposed.

So we deal largely with three types of wood; oak, lime, and pine. All three can be found with applied surface coatings, or finishes, some original and some not. The problems encountered with decorative carving are normally the result of human interference, environmental influences, or insect attack and in many cases a combination of the three.

HUMAN INTERFERENCE AND MECHANICAL DAMAGE

Human interference is often the cause of damage to carvings. Heavy handed dusting with inappropriate equipment has resulted in a multitudes of breaks and losses, some of which are then re-attached in the wrong place, or stored and forgotten. Carvings were added to, cut up, and re-hung, as at Windsor Castle where, in the late 1820s, Wyatt reused earlier carvings in the Waterloo Chamber.

The most dangerous time in the existence of a carving is when being handled by people, as those at Windsor testify. The movement of delicate decorative carving should always be left to experienced conservators as knowing how and where to pick up delicate objects, anticipating problems, and forward planning are integral parts of the conservation of woodcarving. Given care and consideration of the dangers involved, there is no reason that delicate carvings should suffer during movement. Nevertheless it is best to move and touch the carving as little as possible.

Architectural carving also suffers from inappropriate alterations and repairs. Fireplaces, panelling and stairs are painted with no thought to what is being covered up, or its significance to the rest of a scheme. Conversely, where paint is to be removed, there is a danger that paint strippers will be used without first finding out exactly what is underneath, and if it is original. ‘Compo’ for example, an artificial material used in the late 18th century to create embellishments in painted work, can be damaged by some modern chemical paint strippers, and some modern strippers will cause more damage to the wood than the benefits of the paint removal will show. Painted surfaces in historic buildings should always be subjected to analysis prior to any treatment being carried out. Layers of paint are important in their own right, as an investigation of the layers can often give an accurate insight into the decoration of the building over the centuries and can often be used to determine which elements are original and when additions were made. Old finishes should not be taken off without first checking with a conservation specialist. A general rule is forethought, planning and if in doubt, ask. It may ‘only’ be a fireplace, a timber beam, or a layer of paint, but if it is historically important it should be treated as such, and if it is in a listed building, consent will be required for its alteration or repair.

HUMIDITY

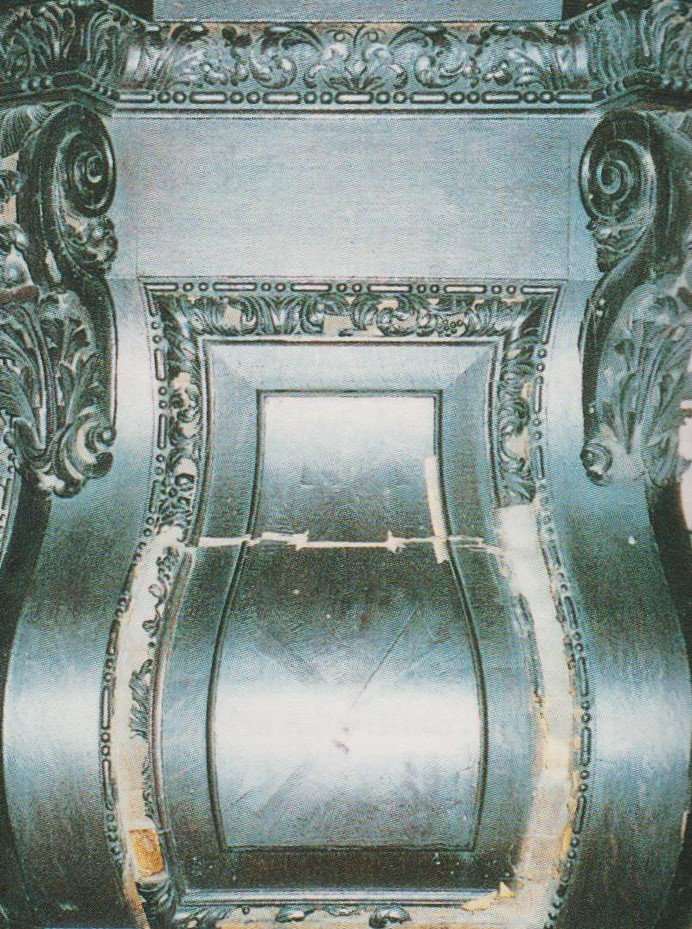

|

||

| Damage caused by variations in grain direction and humidity |

The overriding influence on wood is the relative humidity (RH) of the local environment. In an ideal world the RH would be constant and within the accepted parameters for wood, but this tends to happen rarely. Unfortunately carvings are normally in places where absolute control of the RH is not an option, so while attempting to reduce fluctuations in humidity, treatments have to be carried out that may need to be repeated at a later date.

Wood expands and contracts with variations in RH and these processes put stresses and strains on the carving to varying levels, dependent on the dimensions of the carved details and the nature of the grain. Thin sections will move faster and further than thick, so we can expect to find greater damage to the thin delicate sections, not as a result of mechanical damage but because of their inability to withstand lower stresses.

Variations in relative humidity occur daily and seasonally. The short daily cycles may not effect decorative carvings significantly, but seasonal variations give the carving time to adjust to the new ambient humidity and, in the process, movement will take place. In arid periods carvings will shrink, in moist they will expand. Where carvings are applied to a backing the proximity of the backing reduces moisture loss from the reverse, giving rise to differentials in moisture loss from the front to the back of the carving. So a wide carving with bulk in the middle, thinning to the edges, will curve away from the wall at each side, subjecting the thinner sections to even greater stress. This sort of movement should be accepted and no attempt should be made to force the wood flat, as this treatment would only result in further damage.

The introduction of central heating in the last 50 years has dried out many buildings and caused movement of wood as it adjusts to the new RH, resulting in splits and shakes opening up. During the winter months when the weather is coldest and wettest, the heating is turned on and the windows closed, so with architectural failure and water ingress a high RH may be expected. In the summer the windows are open and air is moving, causing a lower RH. Details with short grain are most susceptible to variations in RH, such as barley twist balusters on staircases and the small-scale carving found on fireplaces. It should be borne in mind that if splits and cracks appear in dry periods they may close up in those with a higher moisture content, and if so should not be filled.

The only sure solution to fluctuations in RH is to create a stable environment, but this is not always an available option. Microclimates can be produced in display cases and some museum environments, but again this is unlikely to be practical in a functioning interior. Usually architectural repairs and preventative conservation such as keeping doors and windows closed, regulating heating, and if necessary using humidifiers, will reduce the impact of fluctuations in RH.

FIXINGS

|

||

| Split resulting from the expansion of a corroding nail (since removed) | ||

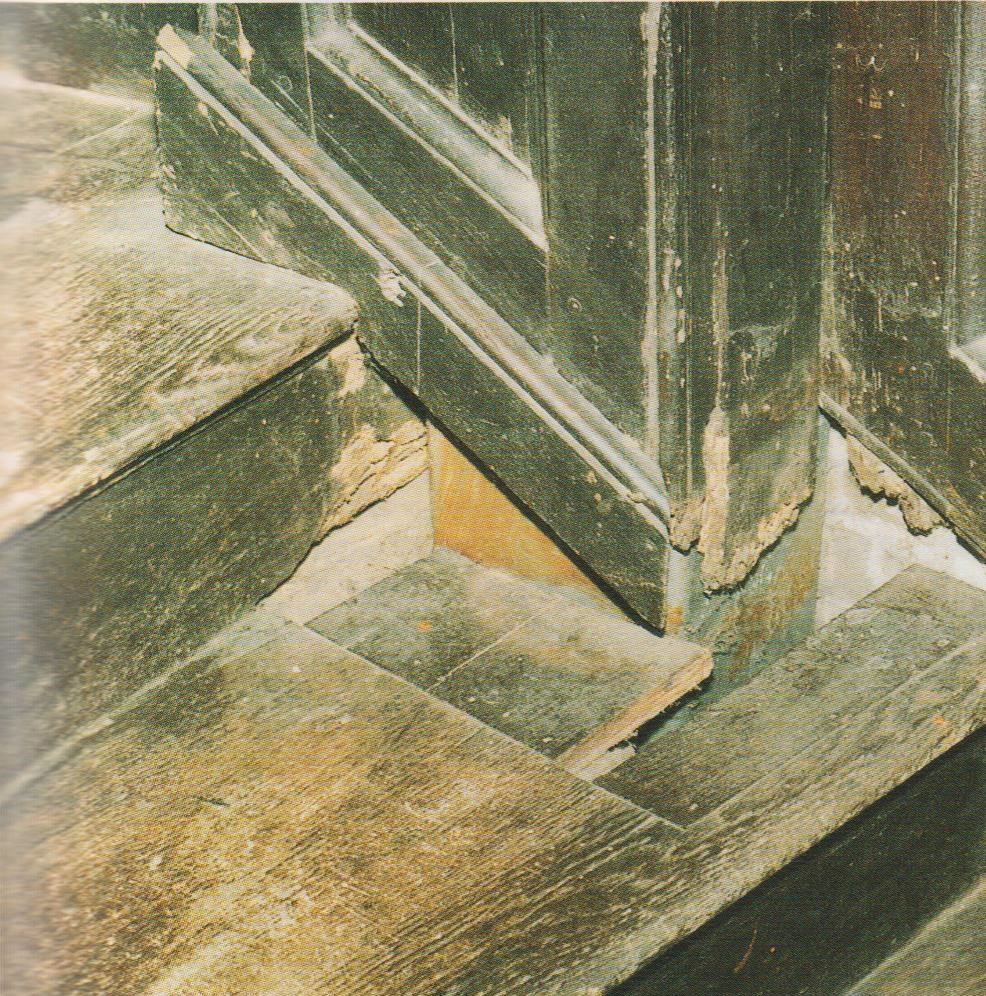

|

||

| Damage caused to the panelling of a Georgian staircase by beetle infestation following the failure of an internal rainwater pipe | ||

|

||

| The result of deathwatch beetle attack in a damp, dark environment | ||

|

||

| Fire damage: in this case damaged and singed areas may be consolidated and painted to match the undamaged areas. |

Ornate decorative carvings in the Gibbons style are usually fixed to their backing with nails or screws. These fixings are rigid and as the wood changes dimension while adjusting to the ambient humidity over the years, stresses and strains are introduced. These can result in the wood splitting and, in some extreme cases, sections of carving can detach from the wall. The wider the carving across the grain, the greater the dimensional change will be. To overcome this problem fixings should be placed in positions to negate stress across the grain, or should be flexible. If the carving is stable there is no reason to take it down merely to move the fixings, but if a carving is taken down for other reasons, the safety of the composition and placing of the fixings should be looked into. Ideally fixings should be stainless steel or brass to avoid rust problems, positioned in thick sections of wood, and in a narrow band of grain. Ideal conditions are rare.

Ferrous fixings also react with the tannin in oak and sometimes fuse with the wood. Extreme care should be taken when removing fixings in this situation. It is normally safer to remove the fixing from the carving after removal from the backing.

Where damp conditions and ferrous (iron) fixings are found together, the added problem of oxidation of the fixings comes into play. Iron oxidises (rusts) in the presence of oxygen and moisture. As well as causing stains to appear at the surface of the carving, the development of rust can cause a nail to expand up to ten times its original dimensions and can easily split wood. During periods of low relative humidity the wood shrinks onto the oxidised ferrous fixings, pushing apart wood already under compression from the expansion of the rusting fixings during the previous damp period, accelerating the cycle of degeneration.

Carving in an incorrect but constant relative humidity may be safer than that in a varying relative humidity that is sometimes correct. Most damp is the result of architectural failure elsewhere in the structure and can be reduced or even eliminated by building repairs. Damp conditions also enable wood-boring beetles and wood-rotting fungi to thrive, so where we find oxidation of fixings we also tend to find timber decay.

INSECT AND FUNGAL DECAY

The most destructive causes of timber decay are the larvae of wood boring insects such as the common furniture beetle (woodworm) and deathwatch beetle, and wood-rotting fungi such as dry rot. Other causes of decay include the effect of ultra violet radiation, which is considered in Rebecca Ellison’s article, and mechanical damage, which is considered above. Both insects and fungi require food (in this case timber) and water to survive, and they thrive in specific environmental conditions. So the first line of defence against infestation or ‘biodeterioration’ is to ensure that the building remains dry, free from condensation, leaking pipes, penetrating rain and groundwater – in other words, preventative conservation.

The problems associated with insect and fungal attack are the reduction of structural integrity ultimately causing the loss of detail as surfaces crumble; insect decay may also lead to the detachment of sections of carving; and dry rot causes the surface of the timber to craze. Oak suffers less than lime and pine from decay, and it is usually only the sapwood of oak that attract insects. If there is an infestation it may be superficial and not require the replacement of the whole oak member. The principal exception is deathwatch beetle, which can be particularly difficult to treat once established in large timbers.

Treatment should start with the elimination of damp, the most effective treatment. Chemicals (insecticides and fungicides) may provide a useful backup where timbers are accessible, providing they are used carefully. But chemicals should never be relied on as the primary means of control, not least because penetration may be limited.

The repair of decayed carving need not necessarily require the replacement of the whole. Damaged areas can be consolidated (always test for reversibility and colour matching) and if necessary filled with either resin, colour matched to the original, or with new timber. This approach not only retains original fabric but is also usually cheaper.

FIRE

Fire damage usually looks worse than it is. Some sections of fire damaged carving can be consolidated and filled, badly distorted and lost sections can be replaced, and both types of repair can be painted to match the surviving original. These methods were used with great success at Hampton Court, and resulted in the retention of far more original Gibbons work than was originally envisaged. It is worth collecting as many fragments as possible, no matter what their condition: a conservator will know which can be saved.

PREVENTION

Preventative conservation measures should be used as often as possible. Carvings should be inspected on a regular basis, ideally annually, and preferably by the same professional, so that any degradation will be noticed quickly. As their condition is effected by their environment, their conservation must be considered holistically, in the context of the conservation, repair and maintenance of the whole building.

Bearing in mind that human intervention represents one of the most significant threats, if there is any doubt as to what to do consult a specialist - it is usually cheaper in the long-term. Whilst it is not always indispensable to have the relevant information immediately to hand, the knowledge of where to acquire expertise is essential. All treatments should be analysed to see if they fit the criteria for the particular situation - it is rare that any two situations would be the same.