Traditional Lime Finishes

and their importance for the future of our churches

Ashley Courtney

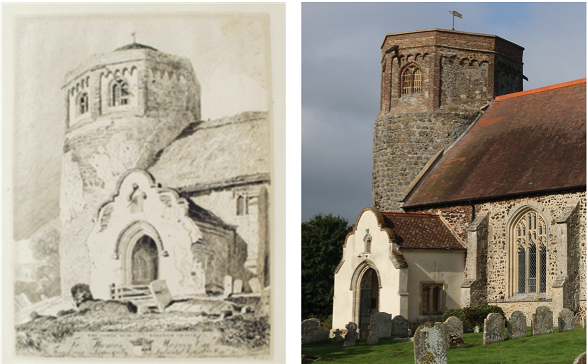

St Andrew’s, West Dereham, with its re-rendered and limewashed chancel, completed in 2020 (All photos unless otherwise credited: Ashley Courtney)

Most if not all of our rural churches are cold and damp and are no place to linger after a church service or event. Is this not a great pity, and have we not become so accustomed to this that we think it was ever thus? After all, what do we expect – if churches are built of solid masonry walls, isn’t the only fix to install better heating?

However, having carried out many quinquennial inspections to over 40 medieval rural churches in Cambridgeshire and Norfolk, I have come to realise that all the churches I look after are missing a vital component of their constructional make-up - their traditional external lime finishes.

Being in East Anglia the local building stones were either of poor quality or non-existent. As a result it was not possible to face a rubble wall both sides with ashlar masonry, with tight regular joints, limewashed both inside and out, as might ideally be the case.

Instead, churches were built with rubble walls comprising local field stone and flint and any offcuts of poor stone that they could get hold of, plastered and limewashed internally, and again, vitally, plastered and limewashed externally. The clue is really in that word ‘rubble’ when you think about it; what self-respecting high status building such as a church would present itself as a rubble wall?

Unfortunately this term has become confused and is used all too loosely, and I am sure there are some cobbled walls that were meant to be left unfinished externally (not to mention knapped flint). And, of course, the Victorians have not helped with their predilection to strip plasters and leave the rubble exposed, both inside as well as out.

To complicate matters further they would very often reface the exterior again in field stones to maintain the look of an ‘honestly’ built wall. Another confusing term is perhaps 'render' itself as this usually refers to the outside and might imply a thick finish, whereas, historically, plaster is applicable both inside and out and need not, I believe, imply a thick finish.

The removal of the original external finishes from medieval rubble walls has done untold damage to the fabric of our churches and while it may have eliminated one maintenance burden, I believe it has created even more serious ones for churchwardens to constantly deal with.

It has also left delicate rubble walling exposed to the elements, allowing water to penetrate much more deeply into the walls. In turn they remain saturated for longer with all the attendant knockon effects to the internal environment and stress on fragile historic fittings.

There seems to be an assumption that renders on church walls are the exception rather than the rule, but nine times out of ten I have found clear evidence that renders and limewash finishes had been applied in the past.

Many of the traces that are left probably date from 17th and 18th century repairs, but nevertheless I am convinced that these builders understood the need and were simply renewing a decayed render.

After all, would not a lime render be considered as a sacrificial coat requiring repair from time to time? The following are typical examples where we found evidence of medieval external finishes and illustrate the signs to look for.

St Andrew's Church, West Dareham, Norfolk

The rubble walling of all but the porch of St Andrew’s, West Dereham is now exposed, but the engraving of the church by John Cotman clearly shows evidence of external finishes.

This is a Grade I church with a Norman round tower. The chancel, nave and tower are built of a local conglomerate ironstone called ferricrete (not to be confused with carstone), but its 15th century belfry is brick.

Windows are built of clunch, a soft stone used extensively in Cambridgeshire, where it was quarried, and weatherings are in a harder Lincolnshire limestone.

|

|

| The chronic condition of the masonry at St Andrew's can be seen in the detail of the tower. |

Somehow the south porch remains correctly plastered, and recently renewed. Evidence on site that the church was plastered is scant, admittedly, although areas of mortar on the chancel would suggest this.

However, it is the secondary evidence that is conclusive to my mind: in the engraving by John Cotman, and then subsequently in a watercolour by his son, the tower and nave are shown rendered.

Later drawings of the chancel, made for the Church Commissioners, would indicate that this too was rendered. Interestingly, the chancel is shown with a traditional thatched roof, and of course without gutters – surely a rubble wall would have needed a covering for protection?

As a result of not maintaining these finishes, St Andrew’s had to replace both of the impressive nave north windows in their entirety when one of them blew out; mercifully, it was at a time when Barrington clunch was available, so the authentic stone was chosen.

The windows were also shelter coated given this is not a hard wearing stone, and after some ten years it clearly needs redoing if they are to last for centuries to come.

Unfortunately, when the east window (patched up over many years) finally had to be replaced last year, Barrington clunch was no longer available (the quarry having been closed – the available clunch was an off-shoot of the cement works anyway).

So, in the end, this was replaced in Hartham Park Bathstone. As for obtaining replacement ironstone these days, you can forget it. The need to recover the tower is urgent and pressing as the surface simply shales away.

St Mary's, Feltwell, Norfolk

The south aisle at St Mary’s, Feltwell: although the clerestory is rendered, the masonry below is unprotected and its condition is poor. Evidence of an external render

can be seen to the right of the east window.

Another very fine and much larger church is St Mary’s at Feltwell. Any render to the 14th-century chancel has been comprehensively removed, although there is a mysterious panel to the north elevation.

However, the south aisle does retain evidence and, given the rubble construction, is it no wonder? As well as having a number of structural issues, the south aisle has peculiar staining on the inside as a result of salt movement spoiling the plaster.

The impressive tower has constant flint falls and I am sure it must have been plastered originally, or at least have had a very full flat pointing struck between the face of the quoin stones.

|

|

| After a partial fall of masonry at St Mary’s, a very old external rendered finish has been exposed, along with limewash. |

Indeed, external finishes may well have started out as an integral base coat of the bedding mortar to the walling as recent research by Tim Meek and Paul Adderley is finding out¹.

When, a few years ago, there was a partial collapse of the south wall of the tower, it exposed the west end of the south aisle, and here evidence of a lime render was discovered. Since the date of the tower is later than the south aisle, this render must be medieval (a sample of it has been retained for further analysis).

Two further points to make: does it not tell us something that the south clerestory is rendered? And the north aisle and lady chapel confuse the issue as they are both Victorian, and their rubble facings (on a brick core) are meant to be exposed.

Although not ideal from the point of view of keeping a solid wall dry, it is clear that a Victorian rubble wall is built in a considerably different manner to that of a medieval one.

In particular, the bedding mortar is more robust, with no voids, there is often a nine-inch brick inner skin, and the external face of field stone, flint, or cobbles are packed together much more tightly.

Something that medieval rubble walls have in common, when you get your eye in, is that the bedding mortars are in a very soft lime mortar, or perhaps even more likely a lime consolidated earth mortar. The masonry units are also much further apart, so there is a greater area of mortar exposed.

Furthermore, there will be many cavities in the mortar, and I suspect these were always present from the date of construction; after all it would be nye on impossible to completely cover every face of every piece of irregular masonry unit, and neither did it matter because it was going to be covered up anyway.

A sign that the cavities are old is the number of cobwebs that cover the surface, as these holes make excellent homes for spiders. However, as a result, these holes create perfect pathways for water to get deep into the core of the wall and saturate the masonry; this in turn means it takes longer for the wall to dry out.

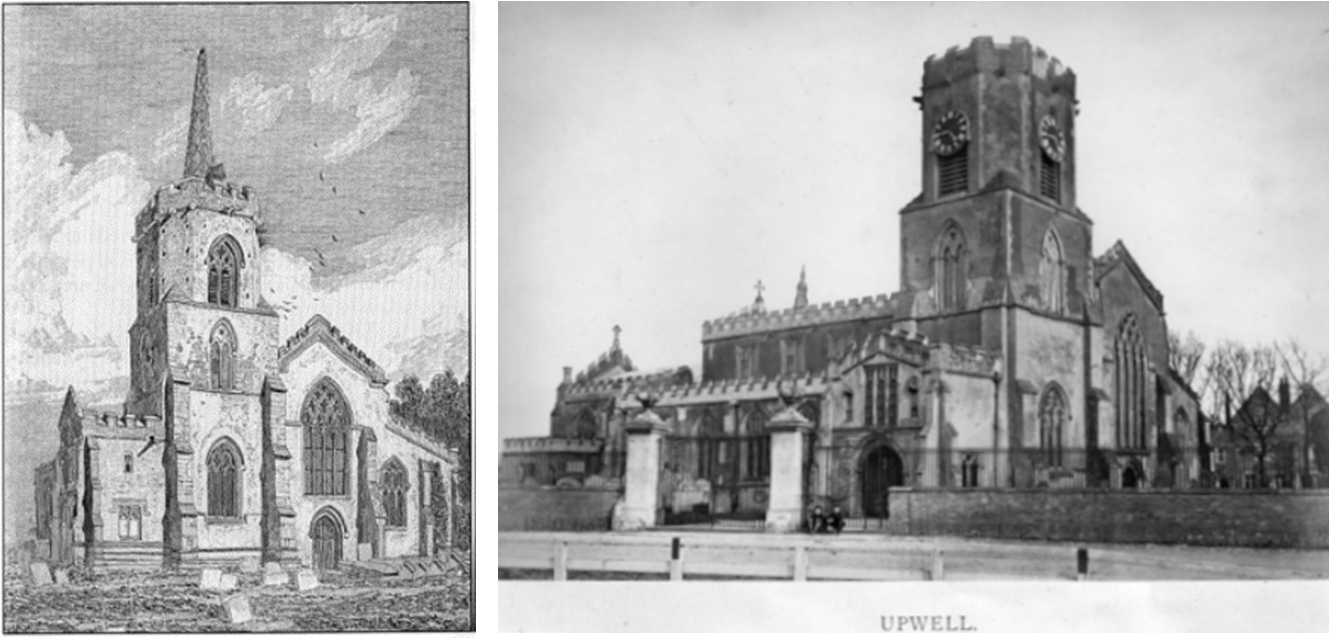

Upwell St Peter Church, Norfolk

Left: An engraving by Cotman, c1817 of Upwell St Peter with uniformly rendered walls. Right: A photograph of the church taken c1882 clearly shows the entire church rendered.

Sitting on the Norfolk and Cambridgeshire border, Upwell St Peter again suffers from the typical problems of a church having lost its external finishes.

Quite apart from its astonishing medieval roof (which needs all the protection it can get), internal plasters are spoiled by damp and give the church a very forlorn and unwelcoming appearance.

Externally, the fabric is in a parlous state with several buttresses on the point of collapse. Apart from the usual issues such as poor drainage, it is clear to me the rubble walling was rendered.

Little evidence remains in situ, but a recent discovery of a 19th-century photograph clearly shows the church entirely rendered, as does another engraving by John Cotman.

The fact that an internal plaster fall at the west end of the nave requires about six square metres of replastering can be no surprise when you look at the decayed ironstone on the external face. Mercifully, we have obtained consent to re-render this part of the elevation, but quite honestly the entire church needs it.

St Mary Magdalene Church, Madingley, Cambridgeshire

The picture of evidence here is a complex one, but on this one church alone there is a multitude of renders and techniques worth looking at. The chancel has been shortened and refaced by the Victorians, and earlier in the 19th century the north aisle was refaced in an extraordinary ‘crazy paving’ effect.

You might like to discount the fact that the two-storied south elevation of the nave has been re-rendered and lined out (early C20, likely a copy of what was there before); and again the Roman cement rendered remnant left on the east wall of the north aisle, and all of the pecking to the dressings which one very much doubts is medieval.

However, older renders do clearly survive and would be worth further analysis. For a start the lower stages of the tower are clearly rendered and are showing signs of slow and inevitable decay of a soft lime mortar over many years.

The belfry stage of the tower was rebuilt (along with the spire) in the 1920s and does not quite match the walling and older render of the lower stages, which is why so many field stones are on view (it is almost as if the mason lacked the confidence to fully render it).

What is most interesting is evidence of render on a buttress at the west end of the north aisle that appears to be very old, and is clearly feathered out over the face of the quoin stones.

This would allow the render to be lined out to give the appearance of polite ashlar masonry, and would overcome the irregular edges and coursing of the dressings.

The render would also, of course, have provided additional protection to the mortar joints of the quoins. The fact that the 20th-century re-rendering of the south wall copies this detail is fascinating.

St Andrew's Church, West Wratting, Cambridgeshire

The poor state of this masonry at Upwell St Peter today, with many hollows and water traps, is typical. The idea of repointing around such decayed rubble seems unthinkable.

This church stands on the highest ground in the county and is therefore unusually exposed. It dates mainly to the 14th century, with a later 15th-century clerestory.

The nave rises through two storeys on both sides as there are no aisles. In the 18th century it was given a makeover in a classical style with extensive interior plasterwork, window tracery was removed and a Venetian window was installed to the east end.

At the end of the 19th century this was all reversed and a neo-gothic east window was reinstated. Again, the walling is of rubble, comprising flint and field stone and a fair amount of clunch stone too, but for the dressings the clunch was replaced by harder-wearing limestone.

Despite all these alterations, there is evidence of render on every single elevation, including the tower, and limewash has been found on the remaining clunch stones around some of the chancel windows.

Quite how old the render is has not been confirmed, but visual assessment by an archaeologist and architectural historian 0 suggests that it is contemporary with the 14th and 15th century fabric.

The idea that such a rubble wall was ever intended to be left exposed is not credible given the parlous state that the clunch and mortar is now in; the walling is incapable of shedding excess water from its surface, and rainwater now simply tracks into the core of the wall making internal finishes damp and green with mould.

Attempts to address this in the past have included taking off the internal lime plaster and replacing it with cement. Given the concern I had over the condition of the fabric, I concluded that the most appropriate method of protecting it was to re-render the chancel.

The Church Commissioners supported this proposition and in 2020 we did just that, limewashing all the window masonry and weatherings at the same time.

Even the masonry to the late 19th century east window was showing signs of decay, and I saw no reason not to protect it and prevent the inevitable piecing in of stone indents in years to come.

Why has it become the norm to appreciate stones covered in lichen and other microbiological growth when they are leaching acids causing slow but inexorable decay?

The Benefits of Render

As for the technical benefits, some may ask whether rendering a wall is significantly better than simply repointing it?

Well, apart from covering over the more vulnerable stones (arresting their decay and avoiding the need for endless cycles of indent repairs and shelter coating), render does have a significant benefit over simply pointing, which is that a rendered wall will dry out much more quickly than one that isn’t rendered.

|

|

| Clear evidence of renders on the chancel at St Andrews West Wratting in 2019. |

Not only will render cover all those inherent cavities but it will also cover miles of interfaces between masonry units and mortar, and water traps, that are vulnerable to water penetration.

Pointing a rubble wall which was clearly originally rendered places an unrealistic onus on the skill of the mason, and I think a medieval mason would be laughing at that prospect.

A well-made traditional hot lime render will also act as a poultice, with a pore structure perfectly facilitating the movement of water molecules towards the evaporation front of the external face.

Limewashes, being pure calcium carbonate with no aggregate, naturally take this further. If you think about it, masonry units and most forms of aggregate impede the movement of water, so the less aggregate you have as you approach the outside then the easier water can move through it (same for the internal plasters).

Of course, by the same token, when it is pouring with rain, such a material will readily soak it up, but it will soon reach saturation and shed water down the face of the wall.

Research has shown that a solid masonry wall in good repair will not be saturated beyond about 100mm from its surface. So, by reinstating the original render we are pulling the moisture out of the walls by the most effective and efficient means possible. This eliminates the decay of rubble stonework and provides a drier wall.

That in turn reduces the strain on internal lime plasters and fittings, and by extension creates a drier internal environment. In addition, removing the drying surface to the face of a render means that the damaging effect of salts is moved to the sacrificial face of the lime render rather than the poor stones found in rubble walls such as clunch, lias and hybrid stones².

As a result of our penchant for ‘pleasing decay’ the fabric of our churches has been greatly compromised, I believe, leading to an accelerated rate of decay over the last 150 years or so, somewhat ironic when we think of the Victorians as the great restorers.

In doing so they have unwittingly created the perfect eco-fridge – cold saturated fabric cooling the interior – everything we have come to expect of a church.

Fortunately, in recent years, developments in the lime revival support the view not only of the historical prevalence of finishes, but also how they actually function.

Many practitioners who have extensively researched this area have found how important and integral lime finishes actually are.

In Scotland and the north of England they have already began to implement this. Stirling Castle, for example, was fully limewashed some 20 years ago, and south of the border, Historic England’s Damp Tower research came to the same conclusion – its findings pertinent not just to church towers.

I would suggest that it is a much better proposition to have a maintenance regime of limewashing than to have a costly programme of masonry repairs every few years.

Hopefully this will be borne out by what we have recently carried out at West Wratting, and West Dereham. I admit this is a complete change of look, but one which I think is beautiful in its own way, and lets everyone know that the church community is alive and well.

To summarise, we need to seriously reappr aise our feelings about what a church is expected to look like, and remember that at its most basic level architecture needs to provide shelter.

It is not good enough to accept that our churches are cold and damp if we are to expect them to have a sustainable use beyond the occasional service. We have to give them back their coats to wear.

References

¹ Tim Meek and Paul Adderley, ‘Harlas-you-go! Integration of mortars and the implications for robustness and longevity in an exposed environment’, The Journal of the Building Limes Forum, vol 26, 2019

² David Wiggins, ‘Traditional lime mortars and masonry preservation’, The Journal of the Building Limes Forum, vol 24, 2017