Traffic Versus Towns

Donald Insall

|

|

|

|

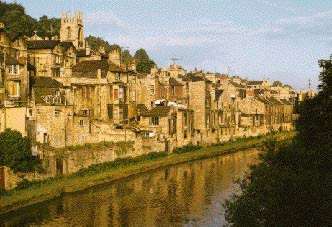

| Demolition for a relief road, Claverton Street, Bath, 1964 and 1966. The loss included not only some fine townscape and Georgian terraces but also one of the city's baths, the Cold Bath House built c1704. Reproduced by kind permission of the Building of Bath Museum. |

THE SHAPE OF TOWNS

The effect upon towns of motor car traffic is not superficial alone, but extends deep into their basic form and function. All over the world, our towns and settlements have initially come together for the sake of immediate human contact - a need which even the benefits of e-mail seem unlikely to reverse. Today, the speed, range and scale of locomotion has forever changed, and with it the shape of towns and the very pattern of human living.

No doubt it was the railways (above all, as they reached out to John

Betjeman's beloved Metroland) which began to disperse the larger cities

like London. But it was the arrival of the motor cars, as just under

a hundred years ago they began to splutter from their coach-houses

into the countryside, which really heralded such a colossal and irretrievable

change in our cities and towns, and indeed in every village.

URBAN

DILUTION

We have to thank the long legs of the motor car, the van and the ambulance

for other new and ever-increasing trends. Already, a rash of out-of-town

supermarkets has reduced many

a previous market town to a shadow. We all enjoy the ready facilities

these bring, although we may lament the loss of the individual service

at the old corner shops which they so often serve to displace and

to starve.

In its turn has come the demise of the neighbourhood schools - small,

perhaps less skilled and specialised in their staffing or equipment,

but warm in human values and in the family contacts which so many

of them once provided. Again, and with increasingly ready transport,

even the largest schools are losing their in-city playgrounds and

playing fields, while urban play areas yield to the profits of population

pressure, and children can be transported by the busload to out-of-town

sites. Hospitals too are finding themselves constantly scattered and

enlarged, in a kind of Rake's Progress away from the local towards

the regional. Everything gets bigger and further apart.

All these and many similar trends are the product simply of advancing

motor transport; and unless in future we run out of petrol and can

find no substitute, they will never be reversed.

THE IMPRINT OF THE MOTOR CAR

|

||

| Central Chester: traffic congestion at The Cross, before the conservation programme | ||

|

||

| …and after pedestrianisation. |

Even more immediately obvious is the physical imprint of car traffic on our urban surroundings. While hard tarmac roadways with paved sidewalks bring huge initial advantages, they do also spread sideways in a kind of tide, overcoming all that was green. Very often the sprawling road-widths are out of proportion with the traffic they carry, so that when it snows, the tracks of vehicles 'read', and almost always display great areas of unused carriageway, left white and undisturbed. We have long recommended that in streets like London's Whitehall, carriageways could be greatly reduced, and whilst more effectively providing fully adequate traffic lanes for very ready circulation, give more space for pedestrians.

The main problem is the sheer scale of

the demand. In our survey of historic Chester, Donald Insall Associates

found that to provide the amount of car parking the central shopping

area was seeking would actually involve a larger land-area than that

it sought to serve.

Town centre traffic tangles generate useful by-passes, but these roads

rapidly find themselves serving additional new development, creating

the demand for yet more by-passes. In London, the now congested Euston

Road was constructed virtually as a by-pass around the north of the

busy central area. And Parliament Square is said to have been adapted

as the first circulatory traffic control system. Following its model,

endless urban junctions have been eased by traffic roundabouts, in

turn greedy of more and more city centre land.

Even one-way streets which overtly ease traffic movement, automatically

and ipso facto involve longer deflected journeys and increase the

car mileage our roads have to serve. Segregated levels offer an attractive

expedient, but in practice require approach ramps of immense length,

using yet more land.

Corner buildings find themselves constantly eroded in favour of sight-angles

for drivers, aimed at ever-faster movement. The roads meanwhile become

barriers to pedestrian circulation. A clear example is the impact

of London's Embankment route, segregating the city from its river

- let alone Somerset House from the Thames.

Another powerful factor in urban traffic nuisance is of course, noise.

The remaining built-up centre of a by-passed historic town like Huntingdon

is now ransomed and ruined by the constant roar of tyres along an

elevated motorway nearby, which in this way - although it looks well

on a map - entirely dominates the place today. Traffic and historic

towns do not mix.

COSMETIC FACTORS

At a cosmetic level, traffic-control devices such as double yellow lines and parking bays, gridded crossings, pedestrian barriers and traffic notices all proliferate, while even the simplest of signalled junctions develops a thicket of red lights on posts. Lines of parking meters stand hungrily in rows, like animals waiting to be fed.

|

|

| Traffic control paraphernalia |

The total actual area taken up by empty standing vehicles alone is

immense, as a walk along any suburban street will demonstrate. Add

to this the necessary turning and manoeuvring space they need, and

one realises why the density and neighbourliness of earlier towns

can perhaps never again be achieved. We live in a motor age.

Time and again, the insulating residential front garden loses successively

its gates and its walls, then its greenery, as first one house and

then another gives in to what is in effect a constantly eroding and

widening traffic strip. The urban 'grain', seen from the air, is thus

entirely changed.

WHAT NEXT?

Yet when all is said and done, how many of us today would be willing

to sacrifice our beloved motor car? And with it, everything we feel

ourselves to have gained, in such ease of ready movement - the very

winged boots of modern life?

So, what do we do? Above all, surely, we must establish our priorities.

Pedestrian circulation, together with living and working space and

conditions must come first. Safety and clean air and quiet take a

high place.

The biggest single improvement in road traffic, immediate and available,

will surely be better public transport. Immense numbers of people,

frustrated by uncertainties and delays, fall back in despair upon

using their own cars. Commuters, especially, then have to leave these

parked empty and waiting all day.

One recent improvement has been in providing segregated bus lanes;

and when responsibly used, these are a great help. Taxi services,

especially in London, are outstandingly good. Underground and suburban

rail services (although irritatingly full of mobile phone users) are

potentially excellent, but it is difficult to improve the actual rails

and routes themselves while they are in heavy use. More road construction

alone is simply not a remedy. Taxation and fuel pricing may have to

be accepted, if only this is wisely reinvested, for example in transport

and environmental improvements. It may be that preferential ticket

pricing might achieve a more even daily demand throughout the day.

Developments in electronic communication and remote shopping, telephone

and video conferencing are influencing our whole pattern of life,

and these themselves may ease the problem by reducing the demands

upon transport. But above all, we need a greater sense of environmental

awareness, and an ever-watchful attention to weeding away unnecessary

and redundant transport equipment and muddle.

Road-building alone is like feeding the pigeons. The more you provide,

the more will come. There is no single remedy, other than constant

vigilance in our common public interest.