After the Tsunami

The impact of the Indian Ocean tsunami on Sri Lanka’s cultural heritage

Pali Wijeratne

The built heritage of a nation – the cherished and familiar landmarks and streetscapes which connect a community with its past and form part of its identity – is never more important than after a national disaster. It is also never more easily overlooked.

Many a scholar has described Sri Lanka as the Pearl of the Indian Ocean for its scenic beauty, golden beaches, cultural riches and mild weather. On that fateful day of 26 December 2004, within a matter of two hours, this resplendent island was reduced to a mere tear drop in the Indian Ocean.

Indonesia, Sri Lanka and the Eastern Coast of India bore the brunt of the tsunami waves which followed the great earthquake off the coast of Sumatra. Other countries affected included Malaysia, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and the Maldives, with lesser effects extended as far as the east coast of Africa.

The causes of the tsunami and the scale of the human tragedy that ensued are now well known as a result of extensive media coverage at the time and since then, as the recovery operation progressed. The focus of attention is, understandably, humanitarian.

However, what is less well known is the impact it had on cultural property. This article aims to explore the Sri Lankan experience and the difficulties encountered in trying to save some of the historic buildings affected. But first, we should briefly summarise the main features of the event.

A little after 6.00am local time, a massive undersea earthquake off the coast of Sumatra was caused by a sudden shift along the fault line between the Indian continental plate and the Burma plate. In the ocean the seismic wave radiating from the earthquake created a ripple effect, escalating as it reached shallow waters to form the huge waves known as a tsunami. Although seismic activity in the Pacific Ocean is monitored to provide an early warning of a tsunami, such events are rare in the Indian Ocean, and not monitored.

At 8.17am on 26 December, the first wave struck Kalmunai in the Ampara District in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka without any warning and continued around the island along the coastal belt to reach Negambo in the North Western coast about 45 minutes to one hour later.

Eye witness accounts from various locations suggest that there were three (or in some areas four) main waves. At their maximum the waves appear to have reached a height of eight metres, though in most cases it was much less. As the waves swept through Sri Lanka’s Maritime Provinces, they caused unprecedented damage to life and property.

It is reported that 26,807 lives were lost, with 4,114 missing, 23,189 injured and 579,000 displaced and the livelihood of more than that amount lost. 62,533 houses have been fully damaged and 43,867 were partially damaged.

EFFECTS ON CULTURAL PROPERTY

The Maritime Provinces of Sri Lanka have an extremely diverse history and a rich cultural landscape that includes some of the most densely populated areas of the country.

Due to the country’s strategic position at the centre of eastern trade routes with the west, this coastal area had been colonised since the early 16th century, first by the Portuguese, then from the mid-17th century by the Dutch, and finally by the British in the early 19th century.

The legacy includes some of the oldest historic buildings in the country. In addition to Buddhist temples, Christian churches, Hindu kovils and Islamic mosques, there are also numerous secular buildings of considerable importance. These include commercial buildings, civic buildings, dwelling houses, markets, port-related buildings, lighthouses, clock towers and others.

They depicted an array of architectural styles varying from the pure vernacular to blends of Portuguese, Dutch and British influences. Such buildings might be described as a mutual heritage, yet the underlying construction philosophy, methodology and materials is clearly Sri Lankan, and the European influences represent a relatively superficial overlay. It is from this ambiguity that the architecture derives so much of its character, interest and charm.

These landmark cultural properties gave a sense of identity to the locality and a sense of pride to the host community. In addition, there was a distinct urban form in which various defence bastions of yesteryear were inter-mixed with more usual urban forms, making this cultural landscape unique.

It was a heritage that was cherished by the local community and admired by visitors.

In some areas, even though large numbers of the host community perished in the tsunami devastation, their monuments survived. Some escaped with little damage, while others were in more obvious need of repair.

However, even before the tsunami, assessing the condition of these buildings had been hampered by the lack of awareness of the diverse range of owners, which included government, various religious organisations, the military, commercial establishments and private individuals. Problems were further compounded by the country’s ongoing political crisis in the north and east, where not all areas are accessible to the relevant officers of the agencies and government departments whose responsible it was to identify such national treasures.

Even though the National Physical Planning Department had embarked on a process of listing such buildings, it was not considered important enough to complete expeditiously. Soon after the tsunami devastation, the professionals in Sri Lanka, the architects, engineers and the town planners, offered their services at no cost to the government to work hand in hand with the technocrats in the state sector in the re-building process.

Surprisingly, this offer was not taken up: the state sector professionals were confident that they could handle the issues on their own. In the meantime non-governmental organisations both in Sri Lanka and abroad pledged their willingness to build and donate houses, schools and other necessary social infrastructure facilities for the affected people to get over their losses.

ROLE OF ICOMOS SRI LANKA

Soon after the event, ICOMOS Sri Lanka set about making its own contribution to the post-tsunami re-development process. With a membership that had seen the devastation at close quarters and some having experienced it as well, the organisation decided that they should attempt to save the cultural property affected.

Before the government started planning for the rehabilitation of the coastal communities, ICOMOS Sri Lanka issued a statement to safeguard the cultural property in the affected areas: that was just three days after the disaster. The statement’s arguments were compelling, highlighting not only practical reasons for saving cultural property and the historic landscape but also emotive ones:

• In catastrophes of

this nature, there is an important socio-psychological and socio-cultural

need for local communities and individuals to see and feel that

the familiar environments with which they identify are not totally

wiped out.

• Conservation and restoration presents a very special

contribution towards preserving and carrying the memory of the

past into the rebuilding of the future.

• ‘Maintaining the familiar’

is one of the most valuable components of the entire restorative

process, helping to 'keep one’s moorings’, to retain identity,

to engender and strengthen a psychology of survival and recovery

in the face of great destruction. (See www.icomos.org/australia/

tsunami.htm for the full statement.)

This statement had its desired effect when the government declared a buffer zone in the coastal belt of Sri Lanka from which all housing and public buildings were to be removed. As a result, cultural properties were allowed to remain, along with hotels and structures related to the fishing industry.

In addition, ICOMOS undertook the difficult task of carrying out a survey of the cultural sites of the maritime belt. This had to be completed as fast as possible to be meaningful for the planners who were designing the post-tsunami recovery process. In order to complete this survey, ICOMOS Sri Lanka invited six universities to help in the process, with ICOMOS members setting out the guidelines and assisting on site as well and the University Grants Commission of Sri Lanka provided the initial seed money for the survey. Though not comprehensive in detailing, the survey was completed in six weeks and the report is now being edited for publication.

Having heard of the disaster and the activities of ICOMOS in Sri Lanka, Tsukuba University of Japan extended the hand of friendship to join ICOMOS Sri Lanka on a long term collaboration to conserve cultural sites affected by the tsunami. The first stage of this joint programme was to select a historically important site that had been badly damaged, to carry out a comprehensive survey and prepare a conservation plan.

The study area selected was the Dutch Fort in Matara, 140 km south of Colombo. In March the Japanese team completed its investigations and on the final day of its stay in Sri Lanka, a summary of these findings and observations were discussed in detail at a workshop held in Colombo. The workshop was attended by architects, engineers, university academics, planners and students. In addition, it was also an opportunity to expose Sri Lankan professionals to disaster mitigation as had been done in Japan not only after the tsunami in 1993, but also after the Kobe earthquake ten years earlier.

Another notable event at the workshop was the presentation of the ICOMOS Survey to the Minister of Urban Development and Water Supply in its draft form. ICOMOS Sri Lanka has decided to continue its efforts to conserve at least some of the threatened cultural property.

The committee set up for the re-development of Matara after the December disaster has invited ICOMOS Sri Lanka to set up a regular advisory/counselling service to those whose houses had been affected by the tsunami. In addition there have been invitations from both Jaffna in the north and the Eastern University for ICOMOS Sri Lanka to conduct workshops in those areas to make the people aware of the values of preserving their cultural property.

Since these are areas of political conflict in Sri Lanka, it is important that we try to use this opportunity not only to develop awareness of the values but also to explore the potential for cultural property to be used as a tool for re-conciliation and peace.

The preliminary survey revealed a much clearer picture of the extraordinary richness and diversity of Sri Lanka’s cultural heritage, much of which had previously been unrecognised due to an inadequate listing process. Listing had previously been restricted to monuments over 100 years old, and most of the buildings on the list were either state owned or religious places.

As a result of ICOMOS’s work, the National Physical Planning Department now intends to protect the properties identified in the survey.

Most of the sites and properties identified are privately owned or religious buildings. As there is no source of public funding in Sri Lanka for their protection or maintenance, ICOMOS Sri Lanka is now initiating the establishment of a ‘National Trust’ along the lines of the British, Australian and Indian examples to help the cause. It is expected that within the next month, this trust will be registered as a non-governmental society for the purpose of preserving both the tangible and the intangible cultural heritage as well as the natural heritage of Sri Lanka.

Of the seven World Heritage sites in Sri Lanka, only the Dutch fort in Galle, 100 km south of Colombo was within the affected areas. There was much concern for the wellbeing of the site from both the local and foreign experts.

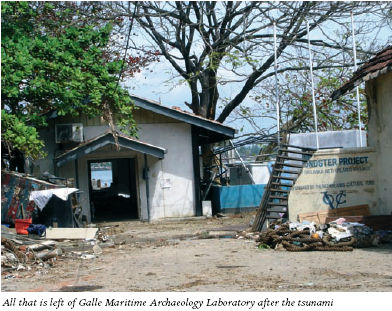

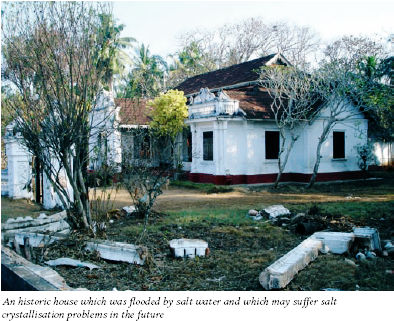

Even though at first glance, there was seemingly little damage to the fortifications of this 17th century monument, a closer inspection revealed fundamental problems, raising serious concerns for the stability of its foundations. In addition, the Marine Archaeology laboratory, which was located on the pier of the adjoining ancient harbour, was totally destroyed, and the sea had reclaimed important artefacts removed from the 17th century shipwreck ‘Avondster’ that were held in the laboratory.

In the year 2000, ICOMOS Sri Lanka had prepared a feasibility study to conserve the ramparts of the fort and presented it to the Department of Archaeology. This was not implemented due to the shortage of funds. It is now vital that the conservation of these ramparts be taken up as a matter of urgency.

The Sri Lankan government is optimistic that the government of The Netherlands will come forward with the necessary funding for a programme to conserve the ramparts and other important elements of Galle Fort.

However, in high profile projects such as this, promoted around the world by both the donor countries and the host countries as ‘conservation’, there can be considerable pressure to reconstruct what was there or what might have been there in the past, and there is a risk that this may lead to conjectural reconstruction, with little historical basis.

It is therefore important that such projects are carefully monitored. A good example of this was the recently rehabilitated Dutch Reform church inside Galle Fort, where much reconstruction work was passed off as conservation, thereby causing irreparable damage to its authenticity. ICOMOS Sri Lanka had prepared a conservation and development plan for Galle Fort in 2001.

The plan was approved by both the Urban Development Authority and the Department of Archaeology but never implemented.

It highlighted the need to extend the boundaries of the designated heritage site to include the harbour and also to re-locate a number of unsympathetic and unauthorised developments which had sprung up in its ‘buffer zone’. This zone is an area which extends 400 yards (365 m) around a listed building in Sri Lanka, in which all development is controlled, and is one of the strengths of the system.

Special regulations were also drafted to care for the building stock within the fortifications. With the post-tsunami re-development plans, these proposals are now to be implemented.

What is also most important in Galle is the old city outside the fort. Even though there was much devastation in the old city area, some old buildings survived and the plans are afoot to restore or conserve them.

A mission from the UNESCO World Heritage Centre, the organisation which maintains the list of World Heritage sites, visited Sri Lanka in March to assess the damage to cultural property. Although the mission was aware that ICOMOS Sri Lanka was already carrying out its own survey, there was no attempt made by the visiting mission to find out its status.

UNESCO and its World Heritage Centre usually work closely with ICOMOS, for example on the recognition of world heritage sites, and look to ICOMOS for guidance and advice, particularly from the latter’s scientific committees. But in this case, they overlooked a very active national committee, and the report contains a number of inaccuracies and omissions as a result, highlighting the need for better communication in any future disaster.

The lack of recognition for ICOMOS Sri Lanka’s activities by UNESCO was, however, amply compensated for by the support given by the ICOMOS family of the world. The sister organisations rallied round Sri Lanka in its hour of need to give help and advice and to send notes of encouragement in the post-tsunami activities. ICOMOS Sri Lanka is grateful to its friends the world over for the strength and encouragement given.

ROLE OF THE STATE AGENCIES

Sri Lanka boasts of several effective planning tools that can be used for the protection of cultural property, with different government agencies carrying responsibilities for implementation.

The Department of Archaeology is responsible for listing monuments under the Antiquities Ordinance and this covers the major sites. Other agencies include the Urban Development Authority and the National Physical Planning Department.

The Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, under whose purview is the Department of Archaeology and the Central Cultural Fund, surveyed and cared for only those structures that were listed under the Antiquities Ordinance. This is a mistake carried out by most agencies in the world to focus attention on the major sites of cultural importance, thereby ignoring socio-cultural values of local communities as well as the group or cluster values of the cultural properties.

As a result many a less important site or cultural landscape has been lost. A good example of this is the City of Galle. While everybody is clamouring to take part in the conservation of the Dutch Fort, the adjoining areas are neglected, despite being equally important in group value terms.

However, in the immediate aftermath of the tsunami the government’s priorities naturally centred on the care of the displaced and traumatised community, the development of employment opportunities and the provision of the necessary infrastructure facilities for the affected families.

Preserving and conserving the cultural property was not on this priority list.

The Urban Development Authority, the National Physical Planning Department and the Coast Conservation Department worked together to map out the strategy in the post tsunami redevelopment process. This was a monumental task considering the speed at which they had to work to get the plans in place, and the logistics worked out.

Fortunately, those in the planning fraternity were positive in their appreciation of the affected cultural property. They showed willingness to accept and conserve any site or building that had architectural quality and cultural importance.

Moreover, urban conservation became an integral part of the designs for re-construction of the townships. This is important from a socio-cultural point. They have realised that a city without its past can be compared to a man without a memory.

The host community is already traumatised by the tsunami disaster. It is the human instinct that in times of stress and depression, they look to their cultural past for inspiration and motivation. The people returning to their own neighbourhoods also require these landmarks to identify themselves with, and hence these buildings and sites provide a buffer against a totally alien neighbourhood.

THE LESSONS LEARNT

Even though the people of Sri Lanka had never before faced such a catastrophic natural disaster, they rapidly picked up the threads of their lives again.

The recovery was fast, although the state machinery and the implementing authorities found it difficult to deliver the goods. Lack of resources created a vacuum in which the owners of cultural property could not be helped in time to restore their prized possessions, and some properties suffered at the hands of ‘antique collectors’ and others looking for building elements to earn quick money.

The tsunami disaster taught Sri Lankans to concentrate on local and regional landmarks in addition to the few ‘big league’ monuments. Many properties owned by the ordinary public could have the necessary ingredients to qualify for recognition as the nation’s heritage, and it is now clear that the nation should not only recognise those properties that belong to the state as the nation’s cultural heritage.

A need for a fund for such disaster mitigation is also a must for the future. Appreciating the architecture of the past is not merely a matter of admiring ‘beautiful’ buildings or romanticising, but rather the recognition and appreciation of the way of life and values of our predecessors, as reflected in the built environment.

This is the architectural heritage of a nation; a heritage that has developed over the centuries in response to the local economic, environmental, social and climatic conditions. This was a call that ICOMOS Sri Lanka took up in order to save the heritage of this country. Only time will tell how successful it has been.