Underpinning

John Addison

|

|

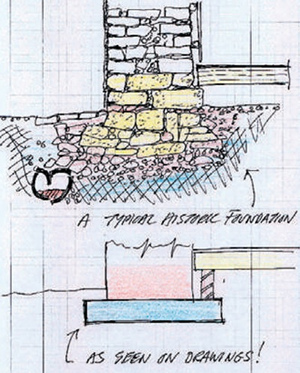

| Above and below left: 'Typical' historic foundations (Drawing and photo: John Addison) |

The subject of underpinning the foundations of buildings is an old and vast one, covered by many experts in books and technical papers. Indeed, in On the Art of Building, Alberti described a basic method which is as relevant today as it was in the 15th century. So it is not intended to review here all the principles involved and the techniques available.

This article focuses more on the practical and philosophical issues relating to the conservation of historic buildings. In this field, the risk of getting the building into more trouble is always higher, and the significance of any omission or failure is far greater than in ordinary structures.

Awareness of the wider issues might result in fewer buildings being unnecessarily damaged and funds wasted. Some attempts at underpinning have resulted in structures becoming more dangerous and, in some cases, the loss of the building. Fortunately experience in old and historic buildings is growing, but situations still arise where full underpinning is planned for cases which require nothing more than the repair of a defective drain.

MOVEMENT AND ITS CAUSES

For a variety of reasons, buildings can settle or sink in whole or in part. Occasionally this happens suddenly in alarming ways, but mostly it is a slow process giving time to consider all the options and to decide on the best course of action.

Settlement is generally defined as the natural compression of the ground under load. The damage it causes is usually of a very localised nature, involving deterioration of the ground or building materials directly underneath the structure affected, but sinking can occasionally occur as a result of subsidence of the underlying site caused by mining, landslip, erosion, deterioration of the ground (such as chalk strata dissolving), or the effects of water table changes. In certain circumstances the building or part of the building could rise due to upward heave in a clay subsoil or chemical expansion. The movement may be cyclical, caused by seasonal expansion and contraction, particularly where certain subsoils are affected by tree roots. These are movements which can occur regardless of the weight of the building, its age, or style of construction, but its historic characteristics will affect the way the building responds to challenges from underneath.

|

Historic masonry is intrinsically far less rigid than modern masonry due to the relative flexibility of lime mortars, and can readily accommodate movement. In many parts of the UK it is rare to find a straight and plumb old building simply because the subsoil compressed under the weight until a satisfactory balance of soil compaction or consolidation was achieved. Usually these movements stabilised achieving equilibrium long ago. Only very rarely does such settlement progress to unacceptable amounts, but when it does it is likely to be caused by structural failure of the ground which can be quite alarming.

Fresh movement can also be triggered by new events or interventions even of a modest nature. Anything that changes the weight in an old building has the potential to cause new settlement in some types of soil. It need not necessarily be extra weight: the lightening of a wall for example could also cause it to rise. The digging of services trenches close to old buildings, or inside them, can incite settlement by increasing the pressure on the soil and at the same time removing lateral restraint to it. The demolition of adjoining buildings can also trigger movement. Alterations can also change how the structure and ground interact.

CORRECT DIAGNOSIS

As a general comment and a stern warning to the uninitiated, the need for ‘underpinning’ an ancient building has to be considered as carefully as a surgeon might consider whether an elderly patient might survive an operation for a new heart or a new limb. In many situations it is as fundamental as that. Also, would a patient contemplate using anybody other than those truly experienced in their field with hundreds of case histories? Likewise where underpinning is concerned, much data needs to be accumulated, historical and factual, tests need to be carried out, monitoring done, calculations prepared, people briefed, and plans drawn-up – but it is not until the operation actually commences that the real issues are confronted. No matter how good the data, there are always assumptions that have to be made. Here, experience assists the engineer to interpret them correctly. Nevertheless, occasionally things can go wrong, new conditions can be encountered, assumptions can be wrong, workers get nervous, the contractor may find that he has priced the work wrongly, and there may be claims for delay – sometimes even before the first sod is excavated.

Underpinning can be a tense operation, not helped by the aggressive business environment of today, with cut-throat tenders and the bullying tactics employed by some less reputable contractors. Funding bodies may often only give a grant to the value of the lowest bid for the work. Clients are stuck with the most trying of circumstances to overcome. A small rural parish, for example, may be wholly reliant on fund raising and grant support to save their church. A difficult technical operation can be made doubly stressful by the extreme considerations of business. Another pressure is the availability of grants and the ‘rules’ for spending them.

Where the project involves the conversion and extension of a historic building for a new use, care needs to be taken to respect the personality and characteristics of the elderly structure which should not be pushed more than it is able. Sometimes underpinning an old building that has already settled can be needlessly forced on an owner as a condition of grant aid or a mortgage solely to remove absolutely all risk to the funding body.

Occasionally, the view may be taken that all its old ‘defects’ should be ‘fixed’, including underpinning the foundations. This may seem wise if the essential new work includes interference with ground levels affecting the footings, but all too often foundation intervention is driven only by the need to rejuvenate everything that is remotely suspect including the earth under the building, just ‘in case it might sink in the future’, and carry away the recent investment in it. A conservation team, including both contractors and consultants experienced in conservation of historic buildings, might be able to prevent unnecessary work, but such a team is not always available when required. Also, a less experienced team is liable to find the politics of dealing with the requirements imposed by other professionals or a mortgage lender too complex to challenge.

PRINCIPLES

|

If the building is becoming unstable by virtue of ongoing movement (settlement, distortion, tilting or cracking) and having decided that the foundations need to be altered or strengthened, there are three basic approaches which can be taken.

In essence these are (illustrated right):

- digging under the walls to construct a deeper, sometimes wider, stronger foundation, usually in concrete, but brickwork, blockwork and stone can also be used

- by-passing the weak subsoil or any inadequate footings with a system of beams and piles or piers

- improving the load capacity of the subsoil by changing its composition with cement grout, lime or other chemically based systems.

One alternative to underpinning is to prop the building and take down the affected wall so that the footings can be rebuilt. Although this is hardly good conservation, in some circumstances it may be cheaper and better overall providing the wall involved is not the most historically or architecturally significant. Other techniques might involve strengthening the sinking wall from above foundation level using concrete beams cast inside the wall or relieving the foundation of its load in other ways without going underground. Usually this is quite intrusive on a historic building, but in experienced hands it can be very effective and safer.

Shoring or tying may also be employed to ensure stability if the foundation settlements or other characteristics have to be lived with.

The selection of the type of foundation stabilisation, underpinning or alteration will depend on many things but first of all it is necessary to decide whether intervention really is needed and the advice of engineers experienced in conservation and foundation remedial work is essential.

ISSUES

There are many issues which arise in the planning and execution of the stabilisation of the foundation of historic buildings. Here are some of the many questions which must go through the minds of the owner or client, the consultants, surveyors and funders of such work in important historic buildings:

The need for action:

- Is the structural distress (for example, cracking, distortion and settlement) really due to failing foundations? Or is it caused by something else (for example, leaky drains, chemical expansion, corrosion, decaying materials, past alterations, loss of bond and tying, thermal effects – ie the new heating system – mining, water table fluctuations, traffic vibration)?

- Is movement still taking place? If so, is it cyclical movement (for example due to seasonal changes in temperature or humidity, or seasonal expansion and contraction of clay) and not progressive?

- How urgent is the work? And do we really need all this worry and stress? Has the building become unsafe?

- What if we do nothing and just pay for filling in the cracks every year? In which case, how should the movement be monitored?

- Is there a risk-free solution or other alternative to the work proposed which involved less intervention?

Heritage implications

- What impact will the work have on historic fabric? Do the benefits to the structure outweigh the harm? (Review the statement of significance or conservation plan)

- What mess will be caused and what will the disruption to surrounding historic fabric be (if only through dust and water everywhere)?

- Are there any archaeological implications? What archaeological remains are likely to be disturbed by digging or piling through? Is an archaeological dig required in advance of the work?

- Can the method or design be easily changed when new discoveries are made? In such an event, would the skills already employed on the job be able to cope with a new concept; how should the revised work be measured and paid for? Will it still be grant eligible?

Costs

- What will the work cost? Is the work ‘grant eligible’ and what proportion of the cost is fundable?

- How long will it take? Can the building remain in use throughout the works? Is it weather dependent?

- Who should execute the work? An expert contractor, or a general builder of perhaps lesser experience appointed on the ‘lowest tender’?

- What if the project runs out of money when ‘extras’ appear (as they usually do) or important archaeology causes delays? What if the designer/expert has to be changed?

- Where is the work on the critical path for the whole project if it is a part of a wider scheme of improvement? Delays here could endanger the whole project and its potential for funding

Contractual matters

- What type of contract should be employed, given the uncertain structural conditions and complex nature of some of the operations involved? Who should run it?

- Is it necessary to ‘do’ the whole building ‘just in case’ if only one part is settling?

- What temporary works are involved (for example, drain and services diversions, shoring and other support work)? Who designs the shoring – the contractor or the consultant?

- What type of insurance cover is needed and at what level?

- How safe is the work? Can the building be occupied during the site operations? How are all the risks to be identified and managed?

- Whose fault is it if things go wrong? What is the potential for delay, claims and falling out between parties? What if the surrounding properties get damaged? And who pays for the consequences?

- Once all the work has been carried out, how does one know if the original problem has been cured? The underpinned foundations may take years to bed-in or settle down and cracking may continue for a while. How is the client to be convinced that his investment and risk-taking has been worth it?

|

||

| Figure 5 Mansfield Church, Edinburgh: underpinning of Baptistry to create access to new offices in the basement (Photo: Stewart Guthrie) |

Historic foundations are never as neat, orderly, squared up and tidy as perhaps the dressed stonework in the walls above. Often they do not conform to any rules of foundation engineers, nor do they even sit at any decent depth. On the contrary, many historic footings can be unscientific, imprecise, shallow, uneven, loose and liable to collapse at the slightest interference with them. Random rubble is common, with or without mortar but often they are built loose with, for example, ‘drystone’ or cobbles dumped into a trench. Timber (mats or piles) can sometimes be found. Others are highly organised, and may be stepped and squared stone or brick footings capable of spreading the load.

In many cases the distinction between the ‘ground’ and ‘footing’ can be rather vague, especially when viewed at an awkward angle from within a shored up excavation. Textbook situations are very rare and if the walls are ten foot thick of random rubble and founded on a slopping layer of stone chippings what does one do? Maybe the signs of settlement are due to these collapsing rather than the soil squeezing, so one needs to be sure.

Some underpinning schemes involve extraordinary feats of engineering, as at York Minster and Malbork Castle in Poland (see illustrations). These unique projects involved large forces, complex ground conditions and sensitive archaeological issues. Risk and high costs had to be considered. Both involved expert consultants and specialist contractors using sophisticated jacking and stressing techniques. However, such cases are rare. More typical is that little church at the end of the village which may be sinking. Here, local professionals and building contractors tend to get involved, all too often without conservation experience. The analysis of foundation ‘misbehaviour’ is complex and for experts to deal with, particularly where historic buildings are concerned.

OVERVIEW

As already implied, the underpinning a historic building will involve disturbing its oldest, deepest, darkest, dirtiest, wettest and least understood parts. It must be avoided if at all possible even with the advances in technology available. The most basic principle in conservation applies ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’. Skill, experience, knowledge, sensitivity and imagination is needed together with good facts and the courage to say that nothing needs to be done. Conservation may be the wise use of resources but it is also about using the resources of the wise: where old foundations are concerned you need both.

‘Expect the unexpected’ must always be borne in mind when planning any operation involving alterations, stabilisation or indeed any repairs to any part of a historic building. In thinking about whether a building needs to receive underpinning it is essential to imagine things that could go wrong and the likely consequences of each.

It is hoped that this article will give an insight into the many issues to be considered in the subject of stabilisation of historic foundations. The ‘do nothing’ option is always favoured in conservation but if something has to be done about a sinking foundation, do it, but carefully. ‘Doing nothing’ however does not mean that nothing is being done – you will always monitor it.