Urnes

and Norway's Stave Church Preservation Programme

Felicity Fox

| Urnes stave church is located in Ornes, in the municipality of Luster, Sogn og Fjordane county, west Norway. (Photo: Olav Stegarud). |

During the Middle Ages, stave churches could be found across Europe and somewhere between 1,000 and 2,000 were built. Today, only 28 remain in Norway, with just three examples in Sweden, Poland and England (at Greensted, Essex).

Stave construction uses solid walls of upright timber posts as a load-bearing component, without wattle and daub or other forms of infill panels. Construction therefore relies on plentiful supplies of timber. The wooden walls, which are raised off the ground by a masonry plinth, consist of posts or ‘staves’ rising from a horizontal sill beam at the base to the wall plates at the top, with vertical timbers between. In the Norwegian examples a complex jointing system was developed to ensure that the corner posts were securely fixed to the beams above and below, and the roofs were supported by elaborate trusses, usually with no ceiling beneath. These churches demonstrate some of the most advanced construction techniques of the Middle Ages.

Stave churches vary in size and style. The simplest examples consist of a nave and chancel alone, and the solid timber walls provide the sole structural support for the roof. However, a mast was sometimes introduced in the centre of the nave to provide additional support for the ridge beam. In the most complex examples such as Urnes in the west of Norway, the nave was elevated on colonnades of staves with aisles on either side.

Like all medieval buildings, stave churches have also undergone a range of visual and structural transformations, moulding to accommodate centuries of new fashions, people and religions. Worn by use and bearing the patina of age and the accumulating evidence of past repairs, each one is unique.

Constructed in the 12th century, Urnes stave church is the oldest of its surviving siblings, although according to archaeological evidence at least three earlier churches had stood on its site. The building’s elevated nave is supported by a total of 14 staves, and is one of the most elaborately decorated of its kind. The romanesque-style building still boasts some of the original features from the church that stood on the site before it, including the richly designed portal and Christian-medieval carvings on the walls. Dubbed the ‘Urnes-style’, this is a viking art-form featuring intertwined animals, heavily influenced by celtic art. It is currently the only stave church to be listed as a world heritage site.

THE STAVE CHURCH PRESERVATION PROGRAMME

The cultural significance of stave churches is well recognised, and they are among the oldest and best examples of Scandinavian wooden architecture. Nevertheless, years of wear and tear and a lack of knowledge on appropriate maintenance resulted in these buildings falling into disrepair.

|

|

| Urnes stave church's poor quality foundations in 2009 (Photo: Sjur Mehlum) and below, a detail of the same wall showing the 'Urnes-style' carvings after the repair of its foundations (Photo: Lene Buskoven) | |

|

|

The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage assumed responsibility for their preservation in 2001 by implementing The Stave Church Preservation Programme, part of an NOK 130 million (c £12 million) government funded scheme to protect Norway’s historic buildings.

The aim of the programme, which ended in 2015, was to avoid losing vital parts of Scandinavia’s architectural heritage. The focus was therefore on preventative maintenance. Conservation principles were closely followed throughout, but first and foremost was the need to authentically repair each church to a standard that can be easily maintained in future. Crucially, this approach applied not only to the building’s structure and fabric, but to its art and interior décor too.

Due to the churches’ structural and visual differences, the strategy required to repair each building had to be flexible, depending on the extent of additional damage uncovered after works began. At the start of each project, a thorough assessment was conducted and a plan devised to meet each building’s repair and preservation requirements.

An important part of the conservation plan was to repair damaged fabric diligently and inobtrusively, rather than fully restoring it back to its original state. Indeed, determining the original state of any stave church would be nearly impossible due to the many alterations and repair works undertaken over the centuries.

The key to the project’s success was the employment of skilled craftspeople who used their specialised observation and technical skills to repair and preserve each building as required while retaining as much of its visible history and original material as possible. They identified techniques to emulate the building methods used during original construction, sourced authentic materials and replicated original tools where appropriate.

Dendrochronology was used to determine the age of the timbers, cross referencing the tree ring pattern of timber samples of a known age against samples from the stave church. As the thickness of each growth-ring varies according to the growing conditions in each year, the grain provides a chronological finger print, and if the outermost rings are present in the timber, it is possible to calculate accurately which year the tree was felled. Conservators were often able to pinpoint the exact age of the wood in different parts of the building, which was useful in helping to determine exactly which kinds of materials and building techniques to use when repairing material from each time-period. This technique was particularly useful for informing the repair works undertaken on Urnes stave church.

CONSERVING URNES

|

|

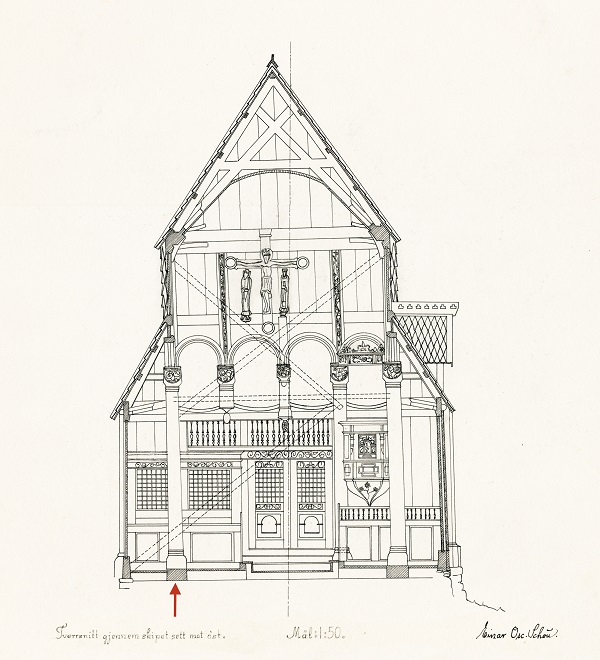

| Elevation showing cross section of the nave at Urnes stave church from the east. Subsidence on the church's north side is indicated by a red arrow and the calvary group is visible in its elevated poition. (Drawing by Einar Oscar Schou) |

Before the most recent repair works began, it was well-known that Urnes stave church was suffering from severe subsidence and structural instability, a problem that had been ongoing for many years. It was by no means the only church with this issue; at the time of The Stave Church Preservation Programme’s inception, several others were also suffering with structural problems.

In the case of Urnes, the existing foundations were in extremely poor condition. Investigation revealed that the cause was not poor drainage but the quality of the stone originally used to construct them. The conservation team and The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage were faced with two options: either to consolidate the existing foundations in situ, or to carefully elevate the north side of the building and re-lay the footings to their original level. The first option was discounted as it could not be certain that it would provide a long term solution to the subsidence problem.

According to Sjur Mehlum, Project Manager of The Stave Church Preservation Programme from 2007 to 2015, re-laying of the foundations was a very tricky process that involved the careful dismantling of the building’s interior to enable the removal of the church floor. This was made all the more difficult with the existence of the northern portal, one of Norway’s most important pieces of art, which was being placed under significant stress by the building’s unbalanced load-bearing system. The imbalance, caused directly by the subsidence, could have had a devastating effect on the church if left unattended, eventually resulting in irreversible damage to its structure.

The stabilisation of the building also served to protect it from further decay to the material around its foundations. Rot to the sill beam of the north wall and other original medieval material were observed, but not repaired as the decay was relatively superficial and the building’s load-bearing capabilities were not affected. Once elevated to their original position the timbers would be dry making further decay unlikely.

In most cases, repair works were needed to the roofs of the stave churches as a result of timber decay following leaks, but in the case of Urnes its roof was still in a reasonable condition and no significant repairs were required.

Once the new foundations had been laid, the floor was replaced and the church interior carefully reassembled. Works to the foundations of Urnes stave church were completed in 2010. However, this wasn’t the last of the issues that needed tending to.

Interior: calvary group and paintings

|

|

| The calvary group after conservation (Photo: Birger Lindstad) |

As previously noted, The Stave Church Preservation Programme also identified that some repair works were needed internally to the building’s celtic and viking style art and décor, with one particular sculpture targeted for preservation as a matter of priority, the wooden calvary group.

The 12th-century sculpture is the oldest and best preserved of its kind in Europe. It represents a wooden carving of Jesus Christ hanging on the cross flanked by the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, and is suspended from the ceiling inside the church.

As an original example of medieval art in a designated world heritage site, a strict policy of consolidation without retouching was adopted, in accordance with the Management Guidelines for the World Cultural Heritage Sites. Consolidation without retouching means that the object marked for preservation must be handled carefully, with as few changes made to the original material as possible.

Under these directions, the fragile calvary group was given a protective coating of varnish to increase its longevity. Some flaking paint on the wooden figures was noted but not restored. Due to the sculpture’s elevated position and the poor lighting in the church, the surface deterioration has minimal impact on its appearance, and visitors can appreciate it as a work of art.

Other key preservation works to the church’s interior included the consolidation of every one of its wall paintings. The paintings, many of which date back to the 17th century, were gently dry cleaned with a soft brush to reduce or remove surface deposits of dust and dirt. No water or cleaning agent was used as this could have inflicted unnecessary damage and might have accelerated deterioration of the distemper. Once the cleaning was complete, the paintings were consolidated with a traditional adhesive made from sturgeon. This particularly fine form of fish glue, which is vapour permeable, acts as a protective layer and will help to preserve the wall paintings for many years to come.

URNES STAVE CHURCH: MOVING FORWARD

Another of The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage’s key aims when implementing The Stave Church Preservation Programme was to fill in the gaps in the information documented about stave churches and to ensure that they can be actively used by the public as a source of knowledge and pleasure.

Throughout the course of the programme, much new and useful information was discovered in relation to the construction, repair and conservation of stave churches. Since the programme ended in 2015, this has been collated in the 2016 book Preserving The Stave Churches: Craftsmanship and Research, edited by former director for The Directorate for Cultural Heritage, Kristin Bakken, and in a series of research articles also by the organisation. The book can be obtained through The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage directly.

|

|

| Wall paintings of either side of the alter in the chancel after cleaning and consolidation (Photo: Sofie Klemetzen) |

These resources have improved Norway’s academic understanding of some of its most interesting buildings, paved the way for further research world-wide and established the information resource needed to help maintain them in future. Indeed, the preservation programme deliberately used local craftspeople and other expertise throughout the project, to ensure that those with detailed knowledge of the stave churches’ preservation requirements would be on hand to assist with future maintenance.

Since the project’s completion, Urnes stave church has been primarily used for tourism and attracts thousands of visitors a year according to The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, although any activity surrounding the protected building is always carefully monitored. Formerly a parish church, the building is still used for a few local ceremonies, but predominately viewed as an important cultural and historical landmark integral to the Norwegian community.

Urnes is one of eight stave churches to be run by Fortidsminneforeningen, a national Norwegian volunteer association that is keen to preserve Norway’s cultural heritage and is instrumental in looking after the building’s many running and maintenance requirements. According to its website, the income turned over by the church contributes to this purpose.

Moving forward, The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, which reports to the Ministry of Climate and Environment regarding the country’s cultural heritage policy, has outlined its strategy for 2017 to 2021 regarding the conservation of its heritage buildings. According to the plan the new national targets for cultural heritage, which become applicable this year (2018), continue to focus specifically on ‘the need for repair, maintenance and ensuring high standards in conservation work, and on the benefits society can derive from the cultural heritage,’ a policy that certainly bodes well for the future of the remaining stave churches.

All photos and diagrams reproduced by kind permission of The Norwegian Directorate for Cultural Heritage, unless otherwise stated.

|

|

| Urnes stave church after repair and conservation works were completed (Photo: Leif Anker) |

Further Reading

Riley Winters, ‘Urnes Stave Church: A final vestige of viking innovation’, Ancient Origins: Reconstructing the story of humanity’s past, 23 July 2017. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y6tvvj7o [Accessed on 22 June 2018]

Kristin Bakken ‘et al’, in Bakken, Kristin. (ed.), Preserving the stave churches: craftsmanship and research, Pax Forlag, Oslo, 2016

Margrethe Henden Aaraas ‘et al’, ‘Urnes Stave Church’, Cultural History Encyclopedia, 1999. [ONLINE] Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y9bybz7q/ [Accessed 22 June 2018]

The Directorate For Cultural Heritage, ‘Architectural Heritage, Innholdsfortegnelse’, The Directorate for Cultural Heritage, 18 July 2016. [ONLINE] Available at: https://tinyurl.com/y9x38x4r [Accessed on 22 June 2018]

UNESCO, ‘Urnes Stave Church’, UNESCO, 2013. [ONLINE] Available at: whc.unesco.org/en/list/58 [Accessed on 22 June 2018]