The Conservation of War Memorial Inscriptions

Frances Moreton and Chris Reynolds

|

|

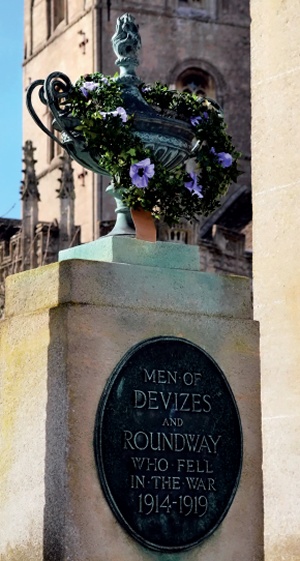

| Detail of Devizes and Roundway war memorial, Wiltshire: with the aid of a WMT grant bronze plaques in the same style as the existing were added recording the names of the fallen post-1939 (Photo: Jonathan Taylor) |

War memorials have a unique poignancy. They reflect a coming together of communities which experienced an unprecedented loss of loved ones. After World War I those who lost their lives were primarily laid to rest overseas at sites few of their family and friends would ever have envisaged visiting. As a result, groups across the nation came together and erected monuments, sculptures, plaques and many other forms of memorial in place of the individual gravestone.

These shared memorials were places to grieve, pay tribute, remember and commemorate, both individually and collectively. Some memorials record just the fallen, others those who served as well. Many were subsequently added to after later conflicts.

As the nation marks the centenary of World War I, attention has focussed on events occurring at memorials such as those found in churches and churchyards around the UK. With over two thirds of our war memorials associated with that conflict, there is huge interest in ensuring they are preserved as a fitting tribute to those they commemorate.

To help communities repair them there are a number of ongoing, and one-off programmes offering support, guidance and funding. War Memorials Trust (WMT) runs a number of grant schemes which support repair and conservation work alongside offering advice and guidance on best conservation practice and day-to-day management of war memorials.

WMT is a partner in the First World War Memorials Programme through which the government is making additional one-off funding of £2 million available to support grants towards war memorial repair and conservation.

While this article will focus on a key issue facing many war memorial custodians – repairing and conserving inscriptions – a wide array of works can be eligible for financial and other support (see Further Information).

As the majority of war memorials were constructed by local committees without any central influence, inscription styles and designs vary greatly. However, the most common form is incised lettering carved or cut into the stone. Inscriptions of this type become less legible over time as a result of weathering, deterioration of materials and biological growth.

Incised inscriptions were occasionally painted or gilded as part of the original design, either for artistic or practical reasons. Over time, paint or gilding can come away leaving an inconsistent appearance. It is sometimes necessary to carry out paint analysis because the darkened appearance of incised letters is sometimes the result of a build-up of dirt rather than evidence of a historic finish.

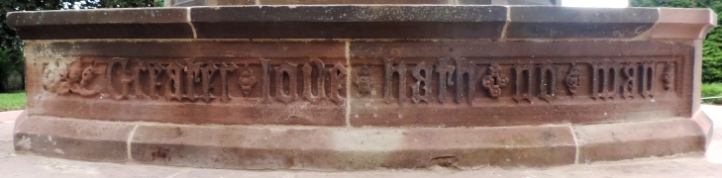

A popular alternative to incising individual letters was to cut back the stone to leave the lettering standing proud (carved in relief), as seen on the Tutbury war memorial in St Mary’s Church, Staffordshire (illustrated below). This style of lettering is often highly decorative and should be carefully managed to avoid damage because more exposed elements are prone to weathering.

Lead lettering is also common on war memorials, for example at St Bridget’s Church in West Kirby, Merseyside (illustrated below). As lead is a soft, malleable metal, lettering can be pressed into the stonework and held in place through pre-drilled holes. Missing letters may be the result of the loosening of fixtures, weathering or vandalism and should be replaced to avoid water penetration into the stonework.

Some inscriptions were added in the form of bronze plaques, as at Devizes and Roundway war memorial, Wiltshire (top illustration). On the whole, these are very durable. However, if it is not maintained, bronze can interact with oxygen, acid rain, pollutants and bird droppings which can lead to corrosion, shortening the lifespan of the metal. Other issues include theft, although this has become less common in recent years. Custodians can apply for free Smartwater (a security marking fluid which improves traceability) for their war memorials as part of the In Memoriam 2014 project to help protect them (see Further Information).

When addressing the repair and conservation of inscriptions, best conservation practice should be followed. This includes:

- only undertaking works which are absolutely necessary

- retaining as much original fabric as possible

- ensuring that any repairs are done on a ‘like-for-like’ basis or with firm historic evidence. If grant funding is sought from WMT, this will be the basis upon which application methods are assessed.

A starting point when considering how to improve the legibility of inscriptions is to consider cleaning, either to improve legibility or reveal true condition. However, all cleaning can be damaging and over-cleaning can increase weathering. As a result, the least aggressive methods should be used in the first instance. These can include using natural bristle brushes and water, steam-cleaning or air-abrasion techniques. If lichen, which may be protected by law, or other biological growth is present then further considerations include the legality of, and potential damage caused by, removal. If you are unsure what type of cleaning is appropriate, WMT’s conservation team is one point of contact for advice.

|

| Raised inscription on the base of Tutbury war memorial, St Mary’s Church, Staffordshire (Photo: Tutbury War Memorial Preservation Committee) |

If cleaning is insufficient to improve legibility, it may be necessary to deepen or sharpen the inscriptions. This should be carried out by hand and done selectively to help preserve original fabric and ensure the longevity of the war memorial. If the lettering has historically been painted or gilded then reapplying this can help legibility. Gold leaf and some types of paint should only be applied with historic evidence because changing the design of inscriptions can not only detract from the architectural significance of a war memorial but also introduce new materials that can cause new problems. Materials should also be carefully chosen to match the originals: some paints for example can block pores in the stonework and cause permanent damage by trapping water.

If the stone is of poor quality, was wrongly bedded (some limestones and sandstones are prone to delamination if the plane in which the original rock was laid or ‘bedded’ is parallel with its face), or has deteriorated to such an extent that inscriptions are lost or cannot be conserved, it may be necessary to replace the damaged stone or panel. However, this should only be done as a last resort and in a similar stone type. Any new inscriptions should be inscribed in the same style as those which have been replaced to avoid impacting the historic and aesthetic significance of the war memorial.

Generally, issues with lead lettering are easier to resolve. An experienced contractor may be able to re-drill the holes which are used to secure the lead to the stone and then gently tap the lead into place and cut it to the correct shape. Replacement letters may need to be painted or coated with a patination oil to ensure they match the existing inscription.

The corrosion of bronze plaques can be more difficult to manage. If fairly stable, the corrosion products or ‘patina’ can offer some protection to the bronze as long as a protective coating is applied such as a microcrystalline wax. However, if the corrosion is active it can cause pitting, pustules, powdering and holes. Any works should be carried out by a suitably qualified professional with experience of working with historic fabric and it may take careful assessment to judge the condition of the metal.

Sometimes the catalyst for a conservation project on inscriptions is an enquiry into the addition of names. This can be challenging for a number of reasons – some designs make it technically difficult to add new inscription or there may be sensitivities associated with a particular memorial’s architectural or artistic significance.

|

||

| Lead lettering on St Bridget’s Church war memorial, West Kirby, Merseyside (Photo: Parish of West Kirby St Bridget) |

Making sure information about the content and design of inscriptions is recorded in detail is an important start. In some cases, approaches may have to be considered which involve alternatives to repair or sympathetic additions. This can include looking at other ways to present information such as information boards, exhibitions or other alternatives. For example, glass walls were added around Southampton Cenotaph after the decision was taken not to re-cut around 2,000 names on the memorial and instead to replicate them.

Making alternative provision is a difficult and often challenging decision and is often a last resort. It can require delicate management of community relations and it can be hard to find a solution which meets the approval of community, custodians, heritage bodies and potential funders.

The principles for dealing with many of these issues are further outlined in a range of available guidance including an inscriptions section on WMT’s website (www.warmemorials. org/inscriptions). Chapter 7 of Historic England publication The Conservation, Repair and Management of War Memorials also deals with inscriptions and lettering, and outlines best conservation practice. Through the First World War Memorials Programme, Historic England is also developing new guidance in this area and 2016 sees the release of a series of short videos with visual, practical examples. Historic Environment Scotland and Cadw in Wales also publish useful technical guidance on the care of war memorials (see Further Information).

For anyone concerned about the condition of their war memorial, either the inscriptions or other elements, contacting WMT is an important first step. The charity can provide advice on appropriate works and how to access funding, with grants of up to 75 per cent of the project costs currently available. This funding, coming through the First World War Memorials Programme and WMT’s own funds, is open to war memorials of all types and dates so whichever conflict your war memorial commemorates and whatever the problems, help is available.

WMT is also committed to an education programme at all levels about the heritage and vulnerability of war memorials and has a learning programme for young people which will inspire future generations to respect and care for the great heritage of war memorials. Anyone interested in obtaining resources around war memorials or arranging a visit from the learning officer to a school or youth group should visit the learning programme website (see Further Information).

War Memorials Trust is a charity with a membership and needs to continue to increase a network of supporters, members and volunteers to ensure that there is a growing national awareness to protect and preserve the memorial manifestations of the sacrifices of the past. Please get involved if you can.

~~~

Further Information

Cadw, Caring for War Memorials in Wales, 2014

Historic England, The Conservation, Repair and Management of War Memorials, 2015

Historic Environment Scotland, Short Guide: The Repair and Maintenance of War Memorials, Edinburgh, 2013