38

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HERITAGE RETROFIT

FIRST ANNUAL EDITION

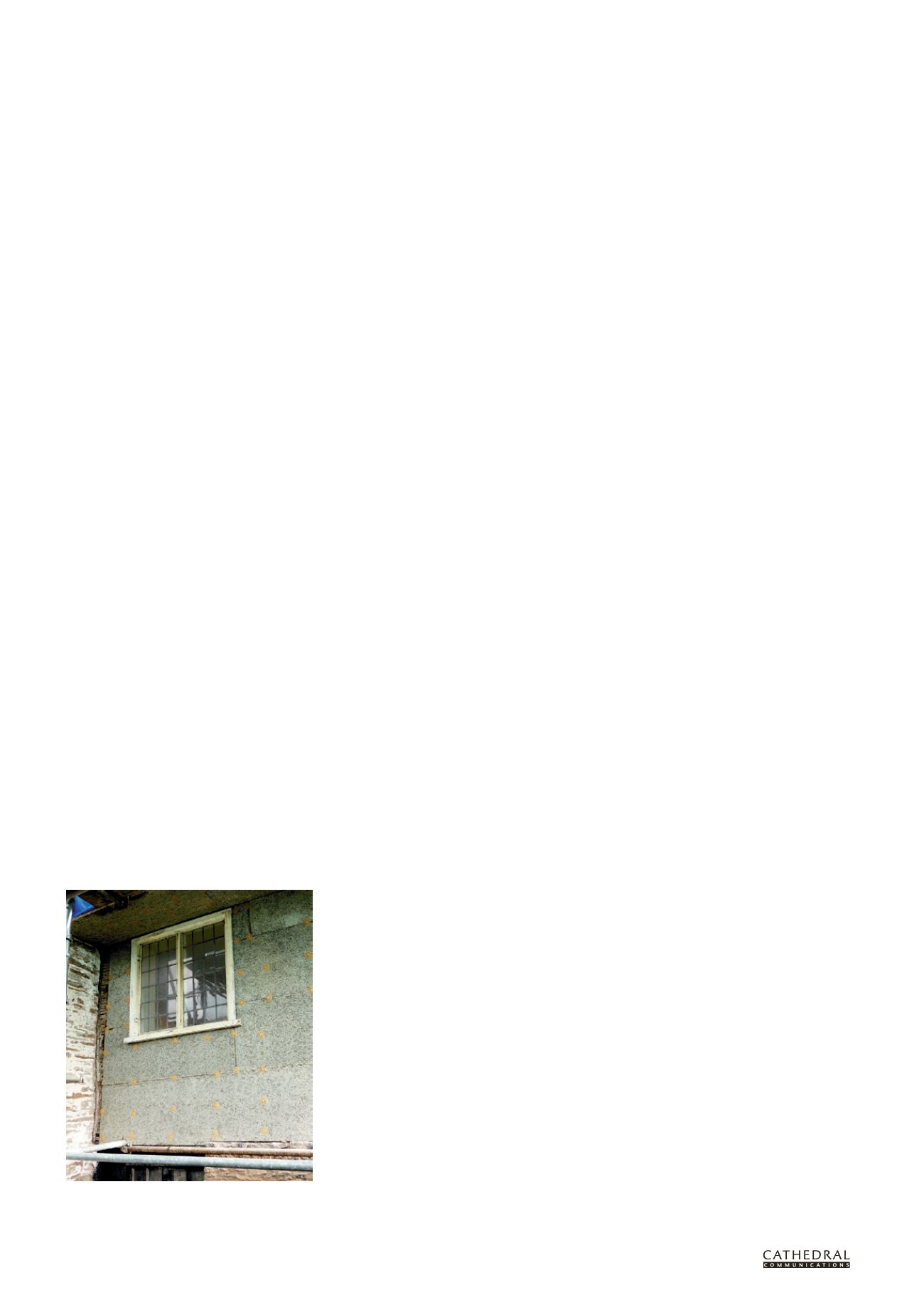

Wood-wool insulation boards ready for lime rendering

and daub as possible. The theoretically

poorer U-value may not be as bad in

practice and the greatest reduction in

heat-loss is often achieved simply by

creating a dry, draught-free structure.

A modern material similar in concept

to daub, but with more durability and

better U-value, is a hydraulic lime/hemp

mix that can be cast in-situ

to form a

homogenous breathable infill.

If the frame and/or the panels are

in poor condition and repairs would

involve the loss of a high proportion of

historically significant fabric, there would

be a strong case for protecting the wall

behind a shelter coat of lime render or

other regionally appropriate material. This

is usually preferable to creating a crude

modern replica of the wall in band-sawn

timber, and may provide the opportunity

to insulate outside the wall line.

INSIDE THE WALL LINE

If the timber frame and infill are in

sufficiently good condition, and are robust

enough to cope with continuing exposure

with limited interventions, insulation

can be fitted to the inside face, either

directly to the wall or with an air gap.

However, this will have a serious impact

on the appearance of the room, obscuring

features such as window surrounds,

skirtings and adjacent ceiling mouldings,

and it will reduce the internal floor area.

More significantly, there is an increased

risk that moisture entering the wall will

become trapped, even if all the materials

used in the new lining (insulation, plaster

and paint finish) are vapour permeable.

If problems do occur, they are unlikely to

become apparent until significant damage

has occurred. The risk of driven rain

penetration can be reduced by careful

gap-stopping and the reinstatement of

overhangs, but any intervention that

restricts the passage of water vapour

through the wall significantly increases

the risk of condensation and/or water

entrapment. For this reason, non-

breathable rigid insulation such as PIR

(polyisocyanurate) boards should not be

used, even though they can achieve better

U-values at relatively small thicknesses.

Insulating inside the wall line also

greatly increases the risk of condensation

due to cold-bridging in those areas which,

for various reasons, cannot be insulated.

In particular, the ends of floor beams and

joists built into the external wall are at

greater risk of increased degradation.

OUTSIDE THE WALL LINE

For many reasons, fitting insulation to the

outside face of a timber-framed wall is

often the best solution, both in terms of

hygrothermal performance and building

conservation.

• The wall is fully protected (assuming

materials and detailing are correct)

• Necessary repairs can be kept to the

minimum structurally required, and

can usually take the form of additional

surface-fixed straps, etc. These repairs

are reversible and involve no loss of

historic fabric.

• Air penetration through the wall can

be fully controlled

• Insulation can be continuous with

all original fabric on the warm side,

reducing the risk of cold-bridging and

condensation

• Keeping what thermal mass there is in

the wall on the warm side also helps to

balance diurnal variations

• The historic significance and

appearance of the interior is not

compromised

• The intervention is reversible.

External insulation will alter the external

appearance: the additional thickness

requires changes to window reveals and

other features, and conceals the timber

frame. This often meets with resistance,

both professional and public. However,

there is a strong historical precedent and

the benefits are considerable.

Historically, render was usually

applied direct to lath nailed to the frame,

and it is widely held that this must offer

good protection to the frame, simply

because it is breathable. However, it is

quite common to find widespread active

Deathwatch beetle attack in timbers

immediately behind lime renders, but

rare to find it in exposed external timbers,

suggesting that sometimes moisture

content of a lime-rendered frame can be

high enough to sustain fungal and beetle

attack. When applying new or replacing

old render, a vapour permeable membrane

should be used and the lath set off the

frame on counter-battens if possible.

The recent development of relatively

high-performance breathable multi-layer

insulation quilts, effectively insulated

breather membranes, has great potential

as they increase wall thickness far less

than most other breathable insulation

materials. Although designed for use in

roofs, these quilts have been successfully

used to insulate timber-framed walls

behind render or weatherboard. New

materials need to be used cautiously until

their long-term performance is better

understood, but equally, they should not

be dismissed out of hand. Furthermore,

imported materials that perform well in

cold dry climates may not work in wetter

UK conditions. Perhaps the best advice is

to question everything.

In a surprising number of cases, what

appears to be a timber frame is actually

an agglomeration of paint, mastic and

cementitious render repair concealing

a severely degraded and structurally

compromised frame. Sooner or later

this will require such extensive repair/

replacement that protection with a lime

render or other cladding would almost

certainly provide a more effective and

conservative solution while avoiding

further loss.

If the appearance of a

timber-framed building is deemed

desirable, this can always be applied

to the face of the new render – there

is a long tradition of what many now

consider ‘fakery’. At least what remains

of the frame and surrounding fabric

is retained for future generations.

RELATED REPAIRS

If the timber frame is to remain exposed,

the essential first step in improving

the thermal performance is to ensure

that the frame and surrounding fabric

are in good condition, and consist of

materials that allow the wall to breathe.

A conflict arises where an alteration

regarded as part of the building’s history

is demonstrably causing damage. Brick

infill for example, does not always

cause problems, but can significantly

increase the rate of degradation of the

frame, particularly when bedded in

cementitious mortar, where frames

are relatively light, poorly constructed

or weakened by decay, or where the

bricks project outside the face of the

frame, creating ledges that trap water.

The use of inappropriate materials is

not the only problem. The introduction

of impermeable materials was usually

prompted by the failure of earlier or

original wattle and daub infill, which

usually began to fail once the protection

of big overhangs was lost. Although