BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HERITAGE RETROFIT

FIRST ANNUAL EDITION

37

of limewash applied. The entire fabric

was therefore very breathable, allowing

any moisture that entered to readily

evaporate, and moisture levels in the

wall generally remained below the point

at which the various materials would

degrade. The walls were protected by large

roof overhangs and pentice boards (see

title illustration), but over the following

centuries, these were lost, causing the

walls to be wetter more often and for

longer periods. As a consequence, the

wattle and daub began to degrade rapidly

and the timber more slowly.

In the 18th and 19th centuries

timber-frames were often concealed

behind facades of weatherboard, brick,

tile or lime render. Early renders were

lime-based and breathable: later renders

were often much less breathable, such

as Parker’s Roman cement which was

patented in 1796.

Where frames remained exposed into

the 19th century, the degraded wattle

and daub was often replaced with brick,

which tended to exacerbate degradation.

Increasing use of cementitious renders,

impermeable paints, damp-proof

membranes and mastic sealants in

the 20th century tended to reduce

breathability and trap water, increasing

degradation and heat loss.

More recently, economic and

environmental pressures to improve

thermal performance have become

increasingly important, but often poor

detailing and inappropriate materials have

exacerbated decay.

In the 21st century there has been a

growing understanding of the need for

buildings to breathe and a consequent

move to more permeable materials. The

crucial point is that impermeable modern

finishes and sealants not only cause

significant and continuing damage to the

timber frame and other historic fabric,

they also greatly diminish the thermal

performance of the wall.

The condition of the wall and its

hygrothermal behaviour are intimately

linked. Unless faults are remedied, the

introduction of insulation may be of

relatively little benefit and can greatly

increase the risk of further deterioration.

Only when the detailed survey has

been completed can the advisability of

retrofitting insulation be evaluated and

the best method selected.

There are essentially three options

for retrofitting insulation to an exposed

timber-framed wall; externally, internally

or within the depth of the frame.

WITHIN THE FRAME

Given that timber-framed walls are often

less than 100mm thick, insulating within

the depth of the frame almost inevitably

involves loss of the existing infill material.

Original wattle and daub should

be retained and repaired if possible,

but where there is a later brick infill, its

historic and aesthetic significance and

its condition may affect the decision.

Where there is evidence of significant

degradation, a good case can be made for

its replacement with a more sympathetic

and better performing material. Where

the timber frame requires repair that

involves removal of the infill, there

is an opportunity to introduce more

sympathetic and better performing infill.

It is now generally accepted that infill

panels should be breathable and vapour

permeable throughout their thickness,

but there are many theories about the

best materials and techniques. Many

recommended systems involve complex

combinations of materials including

synthetic edge seals, breather membranes

and vapour barriers, stainless steel mesh,

wood-wool substrates and softwood

sub-frames. Systems such as these may

work better in theory than in the variable

conditions found on site, where quality

control may be difficult, particularly when

the timber frame is neither straight nor in

perfect condition.

As a rule, the simpler the method

and materials, the more likely they are to

function predictably and reliably. There

is great merit in using methods and

materials as close to the original wattle

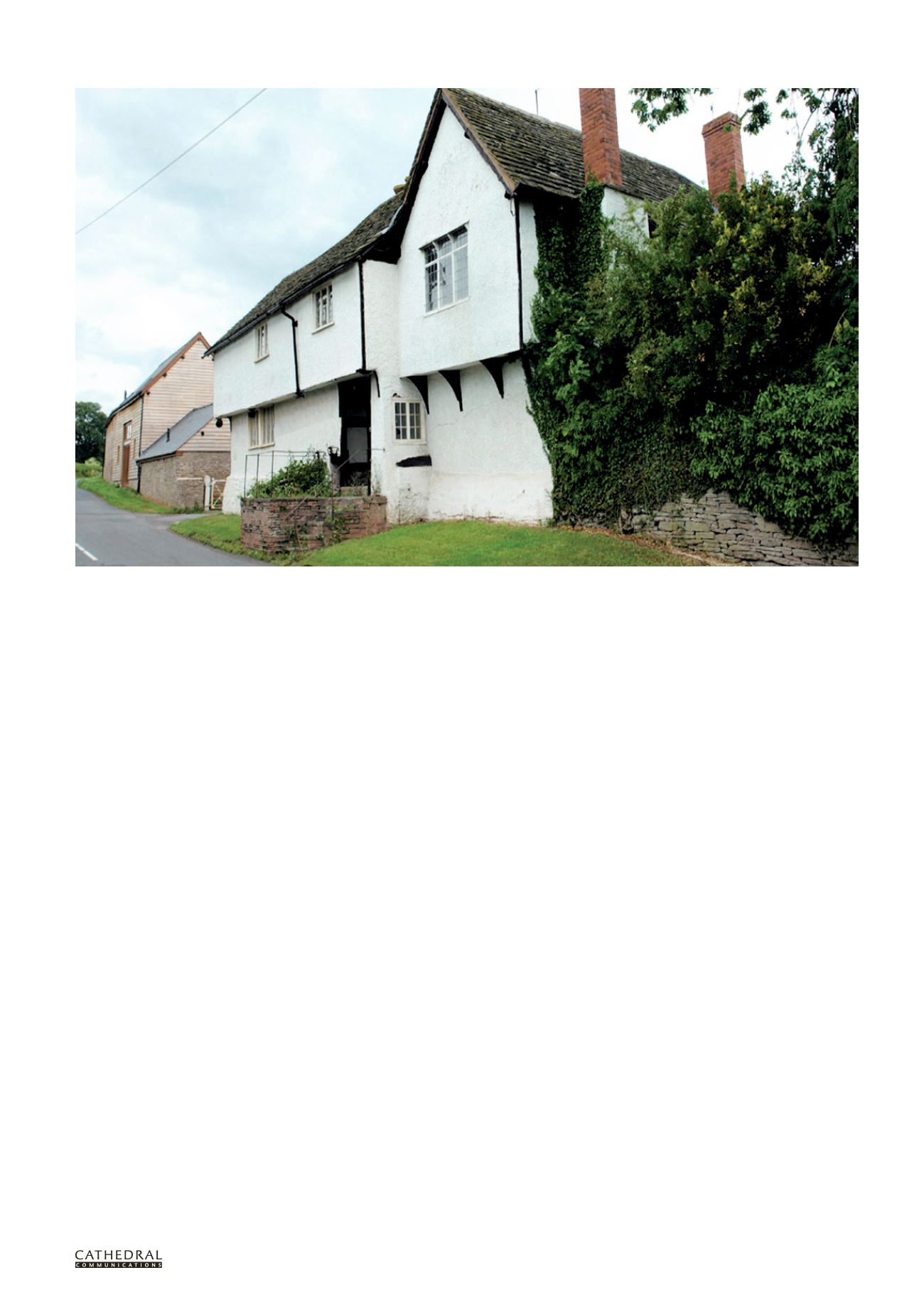

Historically, many timber-framed buildings were rendered to improve their weather-tightness. Some of the visible render is lime-based and probably early

19th century, other sections have been replaced with a cementitious render in the 2oth century.