Monumental Brasses

Sally Badham

|

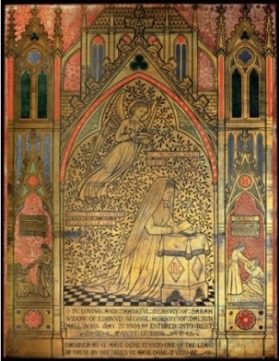

| Victorian brass by Waller of London to Sarah Hornby, 1886, at Burton-in-Kendall, Cumbria (Photo: CB Newham) |

Brasses were popular form of grave marker used to cover the tombs of people buried inside churches, particularly between 1300 and 1600. Fewer brasses were made in the 17th and 18th centuries, but there was a resurgence of interest in the 19th century as a by-product of the Anglo-Catholic revival, and some are still made today.

Monumental brasses developed as an off-shoot from the making of incised slabs, a type of grave marker with the design cut directly into the stone, which were produced in large numbers from the late 9th century. Most incised slabs displayed a cross, sometimes with an inscription, but from the 12th century figure slabs entered the repertory.

There are brasses in Germany dating from the 1230s, but it was not until the 1270s that English manufacturers began enriching incised slabs by inlaying them with ‘latten’ – a brass-like alloy of copper, zinc, tin and lead. Among the earliest surviving examples are two coffin-lids in Westminster Abbey made for the offspring of Henry III’s half-brother William de Valence, which featured brass crosses and inscriptions set against a mosaic background.

Bodily features such as the head were also inlaid on other examples, sometimes with the rest of the figure incised. Our earliest surviving figure brass, at Ashford, Kent shows just the head of a priest dated 1282.

From the end of the 13th century the process had evolved to the point where the entire figure was engraved on brass sheets. When that was done, the monumental brass had arrived.

PRODUCTION AND COSTS

Brass engraving was essentially an urban industry, until the 17th century highly centralised and often employing a high degree of standardisation and mass production techniques. From the beginning, the London workshops dominated supply throughout England. Particularly after the mid15th century, regional workshops, based at major towns such as York, Norwich, Bury St Edmunds, Coventry and Cambridge, served local markets.

Initially brasses were very expensive so full-length figure brasses were mostly confined to the nobility, gentry and higher clergy. In the first half of the 14th century some of our finest figure brasses were produced, such as the knightly effigies at Stoke d’Abernon, Trumpington and Acton (below). Compositions such as these would have cost £15-20. To put this in context, in 1316 an Oxfordshire yeoman paid £18 for a timber-framed house.

Over the next couple of centuries the price of brasses fell and workshops produced more modest compositions. This made brasses available to a wider clientele including parish clergy, minor landowners and better-off townspeople. Richard Willoughby’s 1471 figure brass at Wollaton cost £5 6s 8d, while in 1508 John Feelde left just 10s in his will for his brass at Belaugh, which is adorned with a representation of a chalice. Inscription brasses would have been cheaper still, although patrons willing to pay more could expect a superior product.

Victorian brasses are particularly well-documented. Pugin/Hardman collaborations include the Milner brass at Oscott College, Birmingham, which cost £100, and the Fitzpatrick brass at Grafton Underwood, which cost £91, although they also made cheaper compositions.

THE PEOPLE COMMEMORATED

|

|

| Magnificent military brass to Sir Robert de Bures, 1302, Acton, Suffolk (Photo: CB Newham) |

As well as having an intrinsic interest, brasses act as a picture book illustrating important figures in British history, albeit as representations rather than true portraits. William Catesby, Richard III’s favourite, who was immortalised in Collingbourne’s notorious couplet ‘the catt, the ratt and Lovell owyr dogge, Rulyn all England, undyr an hogge’, has a brass at Ashby St Ledgers, Northamptonshire (below). It has a false date of death in the inscription, to conceal his execution as a traitor after the Battle of Bosworth (1485).

A Victorian restoration of the brass to Henry VII’s father Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond, fills the indent on his original tomb chest in St David’s Cathedral. There are brasses to other public figures related to royalty, among them those at Westminster Abbey to Eleanor de Bohun, daughter-in-law of Edward III and aunt of Richard II, and at Hever to Sir Thomas Bullen, father of Henry VIII’s ill-fated queen, Anne Boleyn.

Portrait brasses to great figures of more recent times include those in Westminster Abbey to the civil engineer and designer Robert Stephenson, the architect Sir George Gilbert Scott, and the last viceroy and governor general of India, Earl Mountbatten of Burma. Alongside these iconic figures are men and women whose names will be unfamiliar to most people. Some may have played a minor role in national affairs, but most made an impact only in their local area. Nonetheless, their brasses remain well worthy of study.

LOSSES AND THEFTS

Some 7,600 pre-1700 brasses survive in the British Isles, mostly in southern and eastern England. This is a much higher figure than the number surviving in continental Europe and makes them an especially valuable part of our national heritage. Nearly 4,200 comprise only an inscription or an inscription with heraldry, although figure brasses have received far more attention. Many more brasses were produced originally but large numbers suffered destruction, particularly during the Reformation and the English Civil War. Cambridgeshire, for example, retains 163 brasses, although 582 lost examples are recorded and many more must have been destroyed without trace.

Cathedrals and major urban churches generally preserve few medieval or early-modern brasses, although the empty stone indents may remain, showing the outlines of the lost plates. Many were destroyed for religious reasons during the Reformation and later: the journal of William Dowsing, Puritan commissioner for the destruction of ‘monuments of idolatry and superstition’ records how on 9 January 1643 he ‘took up 30 brazen superstitious inscriptions’ (ones asking for prayers for the dead) in All Saints’ church, Sudbury. Over the centuries, brasses were also torn up for the value of the metal, which was sold for reuse.

Such losses have been less frequent in the past century, but some thefts still occur and in many cases the brasses are never recovered. In July and August 2002 parts of brasses were stolen from Lacock, Fairford, Beckington, Langridge and Swainswick. The first was subsequently returned but of the others there has been no trace.

Another spate of thefts of treasures from parish churches, including brasses, occurred from 2012 to 2015. Fortunately the perpetrator was caught and successfully prosecuted in February 2016. The artefacts were recovered and returned to the churches concerned. Unfortunately this has not put an end to thefts of brasses, the latest being the loss in early January 2016 from Itchen Stoke of a female figure (final illustration below).

Items which are easily removed are more appealing to thieves. Brasses were originally secured with brass rivets set in lead plugs let into the stone slab and bedded on pitch. Over time pitch deteriorates and loses its adhesion and rivets spring or pull out of the stone. Where brasses are set into the floor, the endless pressure of feet causes plates to expand laterally and bow. As a result, plates work proud of their slabs and become loose and vulnerable. If any part, however small, is completely loose it should immediately be removed to a safe place, prior to professional conservation.

DETERIORATION MECHANISMS

Brasses are inevitably subject to decay over time which requires remedial conservation work, but many factors exacerbate the problems. Chief of these is poor upkeep of the church fabric, including damaged rainwater goods, blocked drains and worn-out pointing, especially when it results in water ingress.

|

| Figure of William Catesby, the favourite of King Richard III who was executed as a traitor after the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, from brass at Ashby St Legers, Northamptonshire (Photo: CB Newham) |

Brasses which are screwed to limewashed walls or are in contact with limebased plaster or cement, are likely to suffer from unseen corrosion on the back. Such brasses are better mounted on a board of chemically-inert wood, which can be fixed to the wall with a small air-gap to prevent a build-up of condensation. Some brasses are set onto the top of tomb chests. Too often these are seen as suitable surfaces for flower arrangements, but this risks water spillage and corrosion. Heavy objects including flower stands and furniture placed on brasses can also lead to damage.

Inappropriate floor coverings – especially foam, plastic or rubber-backed carpets and rubber underlay – trap moisture beneath. Swathing church floors in impermeable coverings inevitably leads to unsightly and damaging green corrosion on any brasses trapped beneath. Coconut or other coarse matting traps grit and dirt which will abrade the surface of the brass or slab. Sometimes loose carpets are fixed with sticky tape, which can cause damage where it runs over a brass.

An even more worrying problem is that some carpet contractors, worried about possible complaints about uneven wear when carpets are laid over old floors, put down a screed of concrete irrespective of whether they leave monuments beneath it and very often without the knowledge or approval of the parish church council or diocesan advisory committee.

All this is not to say that brasses should always be left uncovered, especially when they are worn or in areas of heavy footfall which could itself lead to damage. If they need to be covered then this should be with carpeting with an open-weave backing and the brass and carpet should be separated by a layer of chemically inert felt.

Another problem is inappropriate cleaning by well-meaning parishioners. Some like to keep their brasses polished to a high shine using metal polishes or other chemical cleaners. These contain abrasives and/or chemicals such as ammonia, which can quickly remove both patina and metal from the surface so that, over time, the engraving itself is lost.

It is far better for the preservation of brasses if they are allowed to build up a patina. Usually they only require dusting or sweeping with a soft brush and protecting with regular applications of a micro-crystalline wax. If they are particularly dirty, they should be rubbed with a soft cloth dipped in paraffin and wiped dry. White spirit should not be used. Any blue or green corrosion should only be removed by a trained conservator.

Possibly even worse is the use of abrasive electric floor polishers. Floor monuments suffer as a result of such treatment through water staining and scratching. Where parts of the inlay are lost, tears can develop at the edge of the remaining inlay.

BAT DAMAGE

The most serious problem currently affecting the good preservation of many brasses is bat damage. Bat urine and faeces are extremely damaging to them, as indeed they are to other important artefacts in churches. Bat urine decays to form dilute ammonia, which is chemically aggressive and can cause pitting, staining or etching of porous or polished materials. On brasses it causes corrosion that is evidenced in a disfiguring spotted appearance to the surface.

In the heyday of brass rubbing in the 1960s and early 1970s, bat damage to brasses was a rarity, but this began to change dramatically from the 1980s. By 1995 it was estimated that the total number of churches and chapels in England being used by bats as roosts was 6,398 and this is likely to have increased in the last decade. As a result, the surfaces of many of our historic brasses, including the most significant examples, are being steadily and irreversibly corroded. If nothing is done to prevent it, we face the loss of an important part of our heritage.

|

||

| Above left: Brass at Shottesbrooke, Berkshire to London fishmonger William Frith, 1386, and a priest, perhaps John Bradwell, warden of Bradwell’s college. The brass has been badly affected by bat damage. A photograph of it, taken by John Piper in 1949, was published in The Collins Guide to English Parish Churches, edited by John Betjeman. Piper’s photograph showed the surface to be in perfect condition and another photograph in Malcolm Norris’ Monumental Brasses: The Memorials in 1977 showed only slight bat damage. However, by the time the photo shown here was taken in 2008 the surface was covered by pitting, illustrating that most of the bat damage had taken place over the preceding few decades (Photo: Derrick Chivers). Above right: Stolen brass figure of Joan, wife of John Batmanson, 1518, from Itchen Stoke, Hampshire (Photo: CB Newham) | ||

The presence of large colonies of bats in churches presents major problems for custodians. Bats are protected under European and national law. All species of bats and their breeding sites or resting places are protected by The Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and The Conservation (Natural Habitats, &c) Regulations 1994.

It is an offence for anyone intentionally to kill, injure or capture a bat, deliberately to disturb a bat in such a way as to be likely significantly to affect the ability of any significant group of bats to survive, breed, rear or nurture their young, or the local distribution of abundance of that species. It is also an offence to damage or destroy any breeding or resting place used by bats, or intentionally or recklessly to obstruct access to any place used by bats for shelter or protection.

Because bats are protected, their roosts and access points must not be disturbed. Churches must thus find other ways of protecting their monuments.

Brasses are easier to protect than some other types of monument because most can be covered. It is important, however, that this should be done in a way that does not cause other damage. One solution, adopted at Cley-next-the-Sea and Tattershall is to have metal frames made with cleanable perspex sheeting to catch the bat droppings. These allow free airflow over the monuments. However, they are unsightly and cumbersome to move when a visitor wishes to view the brasses.

Conservation sheeting such as Tyvec (a moisture-resistant, airtight and vapour-permeable membrane) is suitable for covering sensitive surfaces in bat-affected churches. Another possible protective solution is to cover brasses with a layer of chemically inert felt and over that a sacrificial layer of permeable fabric, such as cotton sheeting, which can be washed regularly to remove the build-up of faeces and urine. These are, however, unsightly and may interfere with the liturgy.

~~~

Further Information

S Badham, Monumental Brasses, Shire, Oxford, 2009

J Bertram (ed), Monumental Brasses as Art and History, Sutton/MBS, Stroud, 1996

J Howard, ‘Bats and Historic Buildings’, Journal of Architectural Conservation, 15:3, Donhead, Shaftesbury, 2009

M Norris, Monumental Brasses: The Memorials, Phillips & Page, London, 1977

CM Ward, Our Beleaguered Heritage, Clarendon, Melton Mowbray, 2000