The Exotic Garden:

The Restoration of the William and Mary's Lower Orangery Garden

Terry Gough

In the late 17th century, one of the finest botanical collections in the world was held by William III and Mary II in their gardens at Hampton Court Palace. This collection was a precursor to that at Kew, founded some 70 years later. A current restoration project at the Lower Orangery Garden at Hampton Court is returning the gardens, the glass houses and the plants contained within them to the display schemes first introduced some 300 years ago.

|

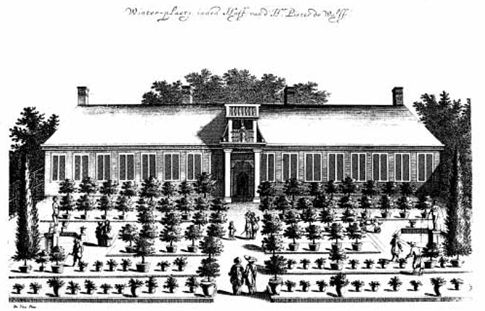

| The Lower Orangery at Hampton Court Palace (© Crown copyright: Historic Royal Palaces) |

When William and Mary became joint monarchs of England in 1689 they brought over with them from William's native Netherlands not only a passion for building grand palaces and gardens but also a love of collecting tender exotic plants from all over the world. Such plants, which are from milder climates than our own and are 'frost tender', may be killed by cold weather. Although these plants may be set out in gardens during the summer, they must be protected during the winter in well-lit and heated structures such as hot houses and orangeries. In their Dutch palaces at Honselaarsdijk and Het Loo, William and Mary had large orangeries built in order to accommodate their extensive collections of tender exotic plants and citrus trees. William's closest friend and adviser, Hans William Bentinck, also shared the couple's love of gardening and plant collecting and had an extensive semi-circular orangery within his own garden at Zorgvliet in the Netherlands. It is little wonder that William, on his joint accession to the English throne, awarded Bentinck the title of the Earl of Portland, for it was an appointment that carried with it the title of the Superintendent of the Royal Gardens of England. William also appointed Sir Christopher Wren to completely rebuild the old Tudor palace of Hampton Court in the baroque style of the period, while in the gardens he appointed the respected gardener George London as Bentinck's deputy.

ESTABLISHING AND DISPLAYING THE EXOTIC COLLECTION AT HAMPTON COURT PALACE

It was a time of great activity at Hampton Court as William and his team of artisans, builders and gardeners went about rebuilding the eastern and southern sections of the Tudor palace and completely relandscaping the gardens and the deer park adjacent to it. It was during this time that Mary fixed upon the southernmost section of the gardens as the area most suitable to accommodate and display her special and extensive collection of tender exotic plants. Due to the extensive building works Mary was forced to move from the old Tudor palace to take up temporary residence in the Tudor Water Gallery building which was located by the river leading into the King's Privy, or private, Garden. Mary had the Privy Garden completely changed from its early Stuart design of simple grass beds or plattes to that of a parterre. To achieve the design intricate patterns were cut into the grass beds and then filled with coloured sand. The garden also had an ornate fountain and a tunnel arbour, and the whole layout provided Mary with a suitable setting in which to display her exotic collection during the summer months.

Mary also altered the old Tudor pond yard which lay to the west of the Privy Garden and which was divided from it by a high wall. She ordered the draining of the 'stew ponds' (which supplied fish to the royal table) to provide three additional walled gardens as setting out areas for her exotics during the summer months. She named these gardens the flower quarter, the orange quarter and the auricula quarter after the types of plants to be displayed there. It was also within this section that Mary had three 'glass cases' or early hot houses built in order to accommodate the collection. This area became known as the Glasscase Garden.

Each hot house was 55 feet (16.5m) long and rested on a Tudor brick wall. The glass sloped so that they were eight feet (2.4m) wide at the ground and five feet (1.5m) wide at the roof. The hot houses were built by the specialist Dutch carpenter Hendrick Floris, and were described by fellow exotic collector and visitor of the period to Hampton Court, Christopher Hatton, as "much better contrived and built than any others in England." The hot houses were heated from the rear of the brick wall by stoves which were essentially large grates on wheels. Four of these were needed to heat each hot house.

|

| Pieter de Wolff's orange house and citrus collection, from Jan Commelin's Nederlantze Hesperides 1683 |

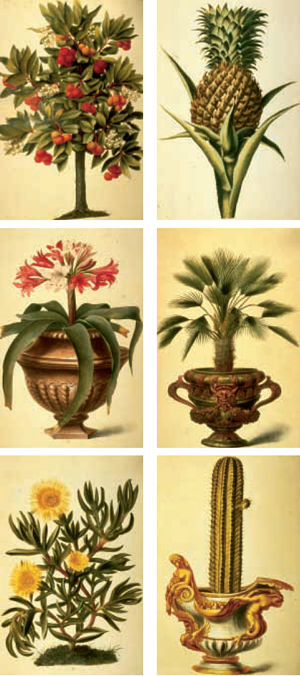

William and Mary's collection of plants contained species such as cacti, succulents, palms, cycads, aloes, agaves, dracaenas, yuccas, coffee, orchids, bulbs and citrus species such as oranges and lemons. The oranges took pride of place within the collection as they represented William's House of Orange dynasty. These plants arrived at Hampton Court from collections previously kept in William's Dutch palaces and from private collections in the Netherlands.

William played a pioneering role in plant introduction when in 1675 he repealed the restrictions on the Dutch East India Company's transportation of exotic plants. As a result the orangery doors of William's Dutch palaces were thrown open to a vast variety of new species and these in turn were distributed to the gardener friends of William, most notably Hans William Bentinck and the Grand Pensionery of the Netherlands, Gaspar Fagel. As a result of William and Mary's devotion, the Glasscase Garden probably held the finest collection of tender exotic plants in England. Indeed the collection was so important that it required the attention of specialist botanist Dr Leonard Plukenet, who was employed specifically to maintain and document it. The advent of these exotics was a testimony to the collectors' courage, the gardeners' skill and the patrons' wealth and status, and they therefore deserved containers of equal splendour.

|

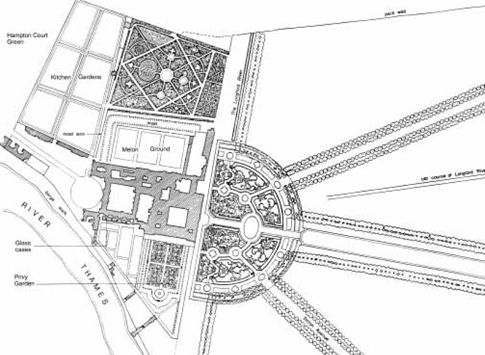

| A plan of Hampton Court Palace around 1690 which shows the three glass cases before they were replaced by the Lower Orangery building. (Travers Morgan) |

A year before William ascended the English throne he had commissioned the artist Stephanus Cousijns to paint the private plant collection of William's friend Gaspar Fagel. With Fagel close to death in the winter of 1688 the project was unfortunately left unfinished. Nonetheless, Cousijns accomplished one of the finest visual records of exotics cultivated in the Netherlands at that time in a document titled Hortus Regius Honselaerdicensis, now held in the National Library in Florence. It is known that following Fagel's death William purchased his collection for displaying within the gardens of Het Loo and Hampton Court and it is therefore reasonable to assume that this purchase also included the wonderful ornate containers as depicted in Cousijn's work. This expanded collection of containers included those made in stone, earthenware, porcelain, lead and bronze, which were painted, glazed or gilded and richly decorated in a variety of motifs, from William and Mary's own monogram to busty sirens, leering satyrs and the leaves of plants such as acanthus.

Such prize exotics collected from places as far away as Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the Cape of Good Hope, North America and Barbados required special treatment, and their position needs always to be carefully considered whether inside or out. During the winter months, when they were in the hot houses and orangeries, the general rule was to place the larger exotics such as oranges and myrtles towards the back of the collection, grading the plants down in order of height to the smallest at the front. During the summer months, when they were outside in the garden sections, the same principles of arrangement applied, particularly to collections placed directly outside orangery buildings in orangery gardens. Exotics were also placed in strategic positions within formal gardens such as around fountain basins, on walls and balustrades and along gravel walks, fully utilising the beauty of these rare plants and their special containers to embellish the garden surroundings. The Glasscase Garden area and the orangery parterre at Hampton Court were therefore not only places of great botanical interest and activity but also areas of great beauty.

|

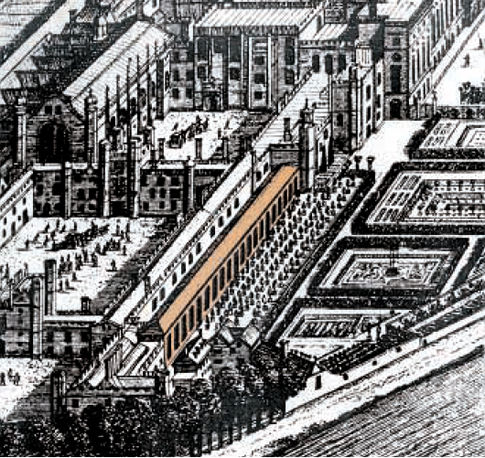

| This engraving by John Kipp shows Sir Christopher Wren's Lower Orangery building of 1701-2 (shaded orange) which replaced the three glass houses. Pots of tender exotics line its terrace and, in front of it, the former fishponds can be seen, now adapted to provide three sunken gardens; the aricula quarter (in the foreground), the orange quarter and the flower garden (behind). (© Crown copyright: English Heritage, NMR) |

Tragically Mary died of smallpox in 1694 at the age of 32, but her botanical collection continued to be maintained and displayed. In 1701 William commissioned Sir Christopher Wren to construct a new orangery to replace the three smaller hot houses which had by then fallen into disrepair. This was a much larger structure which was capable of housing a large number of citrus trees and exotics. This new construction, within the walled enclosure previously occupied by the old glass cases, provided yet another setting out area for oranges and exotics which William named the Lower Orangery Garden. The project to build this structure, together with the recently completed Upper Orangery building within the King's new State Apartments and William's own Privy Garden parterre, further demonstrated the King's passion for displaying exotic plants within his palace garden areas. William died in 1702, and so was not able to enjoy the full fruits of his labours. This pleasure was left to his sister-in-law Queen Anne, and her husband Prince George of Denmark. To celebrate the magnificence of the gardens at Hampton Court during the reign of William and Mary, Prince George commissioned the services of Dutch topographical artist Leonard Knyff. Knyff's work, portraying views from the east and south of the palace gardens, provides us with the finest pictorial record of the royal couple's achievements and confirms Hampton Court Palace as one of the greatest baroque palaces and gardens in Europe.

It is known that the exotic collection at Hampton Court continued to be maintained along with its orangeries throughout the early Georgian reigns. In 1724 Magna Britannia noted that all manner of foreign plants were being maintained in greenhouses with stoves at heats suitable to the climates of their parent countries. George Lowe, head gardener at Hampton Court in 1738, is noted as requesting repairs to the citrus tubs of His Majesty's orangery and two years later requesting new stoves because the existing ones were insufficient for raising pineapples.

THE DECLINE OF THE EXOTIC COLLECTION AT HAMPTON COURT PALACE

|

| Tender exotics and citrus species illustrated by the artist Stephanus Cousijns in Hortus Regius Honselaerdicensis (1689), typical of those imported by William and Mary from glasshouse collections in the Netherlands. Clockwise from top left: bitter orange, Citrus aurantium; pineapple, Ananas comosus; Chamaerops humilis; Cereus peruvianus; Dorotheanthus bellidiformis; and Amaryllis belladonna. (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, Florence) |

The decline of the exotic collection seems to have been a gradual one, starting from the reign of King George III and ending in the 1920s. The start of this decline seems to coincide with Hampton Court Palace no longer being used as a royal residence. It is known that King George III did not reside at Hampton Court and by the 1760s the King was moving exotic plants to his beloved Kew which was to become the leading botanic garden in the country.

By 1838 the Glasscase Garden area was being used exclusively by grace-and-favour residents of Hampton Court Palace as private gardens. It is known, however, that the orange trees from the original exotic collection survived through Queen Victoria's reign, because in 1853 McIntosh refers to Hampton Court in The Book of the Garden as having the largest collection of orange trees in England. A series of postcards depicting the Upper Orangery terrace between 1870 and 1908 show that the number of orange trees declined dramatically during this period. This is probably because the Upper Orangery ceased to be used for plants after 1902 and was altered to accommodate the requirements of the graceand- favour residents.

In 1919 the Lower Orangery was converted into an art gallery and in 1923 author and Hampton Court Palace resident Ernest Law, in his detailed book Flower Lovers' Guide to the Gardens of Hampton Court, makes no mention of any oranges or other exotic plants. He does, however, mention two Judas trees from Queen Mary's collection being removed from their containers and planted in the Privy Garden. It seems unbelievable that one of the greatest collections of exotic plants of the late 17th and early 18th centuries should completely disappear from Hampton Court Palace. It is likely that the reason for this decline was a combination of changes in fashion, usage and economics.

RESTORATION OPPORTUNITIES FOR USING 17TH CENTURY AND EARLY 18TH CENTURY EXOTICS

In 1995 Historic Royal Palaces restored King William III's Privy Garden of 1702 to its former splendour. Part of the project's planting design brief was to highlight the importance of reintroducing the exotic plants from that period in order to embellish the upper orangery terrace together with other strategic areas within the Privy Garden. Historic Royal Palaces utilised the wealth of information contained within the historic accounts to assemble not only historic plants once contained within Queen Mary's collection but also details of the containers which held them. The Privy Garden today displays the embryo of a restored collection for the public to enjoy. Similar restoration opportunities exist for other exotic garden areas within the Glasscase Garden, in particular the Lower Orangery Garden adjacent to the orangery built by Sir Christopher Wren for William III. As well as contemporary published accounts, cartographic, documentary and pictorial evidence has been invaluable in tracing the history of the garden. The Sir John Soane's Museum plan of c1710 shows the orangery and garden clearly defined, possibly much in the manner in which it survives today. There is no indication of the treatment of the central area but there appears to have been a border all around the edge.

By 1732 the area was split into quarters divided by central walks, with a walk around the edge of the garden. This appears to suggest the practice of using beds for spring flowers, which were replaced later in the season by exotics in containers. A similar arrangement is first shown in an illustration of Pieter de Wolff's garden in Jan Commelin's Nederlantze Hesperides c1683. The beds can be clearly distinguished and are edged with box. Philip Miller, in his Gardeners' Dictionary, confirms this practice with an illustration and writes: ".in the Area of this Place, you may contrive to place many of most tender Exotic Plants, which will bear to be expos'd in the Summer-season; and in the Spring, before the Weather will permit you to set out the Plants, the Beds and Borders of this Area may be full of Anemonies, Ranunculus's, early Tulips, &c. which will be past flowering, and the Roots fit to take out of the Ground by the Time you carry out the Plants, which will render this Place very agreeable during the Spring-season that the Flowers are blown."

Beds appear to have been maintained in this area and are still shown there in an 1841 plan. By this stage the beds had been rationalised and related to the steps of the orangery building itself. This situation was altered again, presumably after the collection of exotics was disposed of at the beginning of the 20th century, when the area was transformed into an ornamental rose garden. A study of pictorial evidence, accounts and descriptions of Hampton Court Palace also allow us to identify the types of containers that would have been used in the Lower Orangery Garden to display the exotic collection. For the larger exotics such as orange trees, they used wooden painted tubs with carrying handles in various sizes. Other smaller exotics would have been set out in a range of mainly clay flowerpots and Hampton Court Palace accounts indicate that these varied from plain terracotta pots to those of a highly decorated specification such as those depicted in Cousijns' Hortus Regius Honselaerdicensis.

|

| The Queen Mary's Exotic Collection being over wintered in the glasshouses of Hampton Court Palace Gardens (© Crown copyright: Historic Royal Palaces) |

In summer 2002 the Lower Orangery Garden will be subjected to a series of archaeological trial digs in order to establish what evidence remains for its layout and for the techniques used in the garden. It is hoped that archaeological evidence will confirm the various stages in the development of the garden and the accuracy of the cartographic evidence. This information will be used to assess the scope for reconstructing King William III's Lower Orangery Garden of 1701-2. It is believed that the long narrow beds of the early 18th century layout appear to be the most appropriate for the gardens' reconstruction. A display of historic spring flowers and bulbs is likely to be an essential element of this scheme, providing early colour and interest ahead of the main display of summer exotics.

A study of the plant lists at Hampton Court has provided a wealth of information and confirms that there were over 2,000 different species of exotic plants grown during the reign of William and Mary. Some of these plants have already been collected and propagated within the nursery section of Hampton Court in order to restore a collection for display.

The Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew has very kindly offered to assist Hampton Court Palace in providing additional propagation material for this very exciting project, and a series of drawings is also being produced that will allow prototype containers to be commissioned, from large wooden tubs to the most ornately decorated clay flowerpots. Historic Royal Palaces believes that by extending the display of 17th century exotics to the Lower Orangery Garden it will be reintroducing a method and style of garden display which was pioneered at Hampton Court over 300 years ago. These exotic plants in their beautiful containers, set within their original garden setting, will provide visitors with a unique experience, enabling them to appreciate how these plants were used and displayed in gardens of this period. It will also be a tribute to William and Mary, who to this day remain two of England's greatest horticultural pioneers.