Exterior Lighting Design

Simon Dove

|

|

| A computer-generated image showing proposals for the illumination of the old Corn Exchange building, Manchester (Image: Hoare Lea CGI) |

The majority of our historic buildings existed long before Edison had even thought about his lamp. Today, however, artificial lighting is indispensable both within these buildings and in the wider historic environment.

Any lighting design that affects historic buildings requires creative solutions to ensure that the scheme impacts positively and minimally on the historic environment, creating a visual scene that harmonises the lit appearance of architectural and landscape elements. One of the key challenges is balancing the existing architecture with the introduction of a modern lighting system. How the lighting will render the architecture, in terms of lighting effect and equipment, is central to the success of any scheme.

MINIMISING IMPACT

Lighting equipment should be in keeping with both the architectural scene and the surrounding landscape or townscape.

When working on a historic building it is important to limit the impact of the luminaires on the exterior fabric. This can be achieved by careful positioning, minimising the size and number of fittings, and using bespoke fixings. The rise of LED technology has seen the introduction of smaller fittings, allowing installations that are almost invisible during the day. As well as reducing physical impact, LEDs have low running costs and long lamp life.

The location of luminaires is crucial. Wall-mounted luminaires can help to remove visual clutter. In narrow lanes and thoroughfares, for example, mounting luminaires on an adjacent building can allow for a cleaner appearance. If sympathetically located, luminaires can add a lit rhythm to the facade, highlighting or accentuating structural elements. This does, however, depend on the suitability of the facade and the architecture of the building, which will often dictate the mounting locations.

Mounting luminaires to the building will generally be a cost-effective method, as it removes the requirement for columns. However, column-mounted lanterns can introduce flexibility because their location, height and spacing are not dictated by the profile of the facade.

It is also important to consider light containment and how to provide power and control to the luminaires. The historical significance of the King’s Bath, which lies at the heart of the Roman Baths and Pump Room complex in Bath, meant that the location of luminaires was dictated by existing fixing positions and existing wiring routes were used wherever possible. Projectors were fixed with a bespoke bracket that allows them to be easily accessed for maintenance, while the clamping method used to attach the projectors prevents damage to the structure.

TRADITIONAL OR CONTEMPORARY?

The style of luminaire and how it will sit in the historical context must be carefully considered. Traditional designs can be used successfully, but there is a danger of such fittings creating a feeling of pastiche. It’s also necessary to consider whether the design objective is to replicate the past or to bring a new visual enjoyment to the building. Specifying a luminaire that is in keeping with the building but is functional and efficient is the aim.

|

|

||

| Above left: a contemporary approach to lighting in the Learning Courtyard at Hampton Court Palace, with LED downlights mounted in the canopy of the new reception building and LED uplights in the soil of the edge planting, emphasising the texture of the historic brickwork. Above right: Energy-efficient LED light fittings installed at The King’s Bath, Bath, with warm white for the limestone walls, and a relatively cold, fresh light for the algae-rich water below. Existing fixing positions and wiring routes were used wherever possible to avoid damaging historic fabric. (All photos courtesy of Hoare Lea Lighting, ©Redshift Photography) | |||

The Clore Education Centre at Hampton Court Palace comprised a new single-storey reception building, an external courtyard and the refurbishment of the 17th-century barrack block to provide new educational facilities for visitors. It was vital that the design complemented the architecture, while using the latest technologies to ensure longevity. In the Learning Courtyard, the solution depended heavily on the architecture. Ambient lighting is created by a mixture of new and existing Windsor lanterns, which are highly traditional, attached to the 17th-century barracks. For the new buildings a more contemporary approach was taken with LED downlights mounted in the new reception canopy and LED uplights in the soil of the edge planting. The result successfully blends the traditional and the contemporary.

LIGHTING FROM WITHIN

Using light from within to highlight a building at night can also be highly effective. At the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, one of Sir Christopher Wren’s most celebrated buildings, the brief was to design a scheme that would improve the quality of the lighting and bring equipment up-to-date, while remaining sympathetic to the historic surroundings.

Concealed within the window sills, the luminaires cannot be seen from normal viewing positions. Asymmetric lenses were fitted to cast light inwards, away from the glass, providing washes of light to the window reveals and vaulted ceilings in the upper and lower galleries. In addition, linear fluorescent luminaires were selected to mimic daylight, rendering the colours of the interior far more naturally than could be achieved with incandescent luminaires. The effect is dramatic and has greatly improved the building’s street presence, allowing users to enjoy the volume of its interior space as a feature of the streetscape at night.

SYMPATHY WITH ORIGINAL DESIGN INTENT

It is sometimes possible to go beyond a successful replication and realise the original design ambition by using technology that was not previously available.

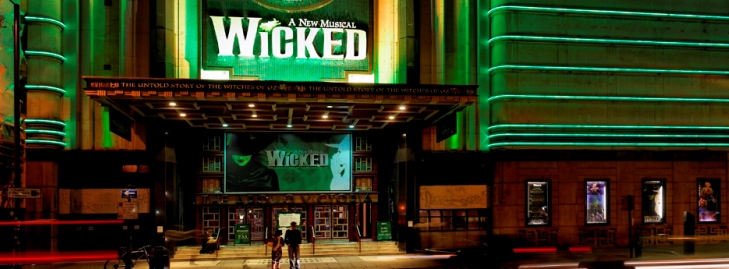

Hoare Lea Lighting was commissioned by architects Jaques Muir and Partners to restore the facade of the 1930s art deco Apollo Victoria Theatre, London. The idea was to recreate a scheme originally envisaged by its architect, Ernest Wamsley Lewis, but which he could not achieve at the time due to technical problems. In a 1973 interview, Wamsley Lewis explained that his intention had been to incorporate bands of green lighting into the original facade. Horizontal housing slots for lighting still survived on the facade, indicating the correct position for the linear lighting treatment and enabling the scheme to be accurately completed.

The obvious choice was cold cathode lighting as the neon lighting systems available in the 1930s used similar technology. However, the lighting design team wanted to improve on the power consumption, durability and colour. With the help of LED manufacturer NJO, a fitting was developed with similar characteristics to cold cathode lighting, but with the advantages of colour changing and energy efficiency. The result is a flexible design which enables the lighting to support the promotion of the current production (Wicked) as well as a variety of future shows.

WHITE LIGHT/COLOUR TEMPERATURE

One of the fundamental requirements for a pleasant lit environment is the use of luminaires equipped with a white light source such as metal halide, compact fluorescent, or LED. These lamps have superior colour rendering properties, allowing colours to be seen more naturally and creating a more comfortable environment.

At night, eye sensitivity changes to the ‘dark-adapted eye’ which is more sensitive to the blue end of the spectrum, meaning we can see better under white light sources.

Lamp colour temperature can create different moods and impressions. A warm 3000K temperature would create a softer more comfortable atmosphere while a cooler 4200K is crisper. At the King’s Bath (title illustration) the warm natural colours of the stone are complemented with warm white LEDs, while cooler 4000oK colour temperature lamps emphasise the green of the algae-rich water.

|

|

||

| At the Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford, townscape interest is achieved by leaving the exterior walls dark and lighting the interior instead. | |||

ENERGY AND MAINTENANCE

Low energy use and low maintenance were important requirements in the lighting design for the Edwardian facade and entrance of the Grade II listed Corn Exchange in Manchester. The building has been refurbished and rebranded as a food and retail destination and the lighting design formed a central part of this transformation.

The new lighting scheme adds definition, drama and interest, while showcasing the historic architecture of the Corn Exchange and reinforcing its position as a Manchester landmark. The lighting shows the form and fabric of the facade through colour temperature, variation in luminance levels, contrast, shadow, grazing (directing light across a surface to emphasise texture), uplighting and a respect for the architectural detail.

Custom-made adjustable bracketry allowed the installation to meet the complex mounting requirements created by variations in ledges and sill details and to avoid penetrating the lead weatherings, while ensuring that fittings were positioned and aimed as required. The scheme is carefully integrated, with light fittings coloured to match the lead on the building ledges. Care was taken to ensure that fittings do not protrude beyond the ledge, making the installation effectively invisible.

DESIGN PROCESS – PLANNING

Historic buildings are generally well protected and any change which affects the character of a listed building requires listed building consent. Such restraints combined with discerning stakeholders, serve to protect sites from inappropriate lighting.

The effect of a proposed external lighting scheme on a sensitive building or space can be difficult to appreciate. Computer generated imagery (CGI) can play an important role here, allowing lighting designers to show clients and design teams how the building will appear and to explain the nuances of the proposed design. CGI was used successfully during the Corn Exchange project (see top illustration), assisting with the planning process and helping the team to understand the proposed scheme, especially those unfamiliar with the technicalities of lighting design.

OBTRUSIVE LIGHT

An exterior lighting scheme is a key component of the night view and we must be mindful of ‘obtrusive light’. This term describes poorly controlled and distributed artificial light, which results in adverse impacts to the surrounding environment. Obtrusive light impacts can include:

- sky glow: the upward spill of light into the sky, which can cause a glowing effect and is often seen above cities when viewed from a dark area

- light spill: the unwanted spillage of light onto adjacent areas, which may cause problems for residential properties and ecological sites in particular

- glare: the uncomfortable brightness of the light source against a dark background, which dazzles the observer; it may cause nuisance to residents and a hazard to road users

- light trespass: the spilling of light beyond the boundary of a property, which may cause nuisance to others.

Obtrusive light has negative impacts on the visibility of the night sky, on the night-time appearance of buildings and landscapes, and on wildlife (especially bats). It is only relatively recently that policies and good practice guidance (see further information) have been produced to address these issues, and establish limits and measures to control obtrusive light.

To minimise and mitigate potential adverse obtrusive light effects on the environment, the following measures should be considered at an early design stage:

- flat-glass light distribution: this eliminates direct upwards light, the primary contributor to sky glow

- minimal column heights: this can reduce the light footprint and any resulting overspill (however, shorter columns invariably lead to an increased number of lighting points)

- switching off or dimming unnecessary lighting during unoccupied hours (subject to health and safety approval)

- light-controlling shields: these provide a cut-off to the light distribution; within a good design scheme they are a last resort and are usually applied post-installation

- sympathetic and sensitive design in relation to night-time lit effect, luminaire finish, positioning, fixing methods and the overall appearance of the installation during daytime

- planting and retention of trees on the site: trees provide a natural method of screening; the best effects are achieved with dense, evergreen species.

TECHNOLOGICAL ADVANCES

Advances in the manufacture of light fittings and light-source technology have resulted in the production of lighting ranges which are suitable for the most sensitive environments. For example, LEDs have the benefit of putting light only where it is wanted. Similarly, research has shown that our visual acuity is improved when using white light in lower lighting levels, resulting in a reduction of illuminance levels where specific sources are selected.

|

|

| Ernest Wamsley Lewis’s original 1930s lighting scheme for the Apollo Victoria, London was only recently made possible by the development of LED lighting technology. The new scheme uses the original housing slots for the first time. |

Such advances allow for visibly lower levels of obtrusive light. Improvements are constantly being made in the control of light and their implementation should see a steady reduction of obtrusive light.

MASTERPLANNING

Recent technological advances are perhaps most evident when considering the process of designing a lighting masterplan. Here we have to use everything modern technology has to offer, while carefully considering a range of different building styles and uses.

Our towns and cities grow organically and external lighting provision grows with them. No single style of lighting predominates – different styles, fashions and techniques provide interest and variety as a city evolves.

While designing the external lighting masterplan for a development in Oxford, Hoare Lea studied existing lighting in the city. By taking cues from previous installations it was possible to ensure that the new installation was comfortably integrated into the city’s nightscape. Mounting methods, colour temperature and illuminance levels were all considered, so that while modern, efficient luminaires were installed, the feel and aesthetic is very much an extension of the city.

MINIMAL, TARGETED LIGHTING

The future of the nightscape is positive as luminaires become smaller and more efficient, guidance becomes more focussed and the night sky is cleared of the ‘sky glow’ still common in many towns and cities. Heritage buildings play a vital part in showing the public what can be achieved when minimal light is targeted in a considered way.

Whether or not to light a building at night is itself a significant question, especially in terms of sustainability and energy consumption. However, public visibility is increasingly important for heritage sites. For example, historic buildings which are open to the public typically need to attract visitors throughout the year in order to maintain their balance sheets – so a night time street presence is important. The key is to light with the minimum number of fittings, the lowest energy use, the most efficient maintenance regime, and with luminaires which have little or no aesthetic impact on the building during the day. Recent advances in technology have finally brought these objectives within reach.

~~~

Further Information

The Institution of Lighting Professionals, Guidance Notes for the Reduction of Obtrusive Light, 2011

Bat Conservation Trust, Artificial Lighting and Wildlife – Interim Guidance: Recommendations to help minimise the impact of artificial lighting, 2014