Scheduled Monument Consent

Robin Kent

|

||

A modern intervention in a ruined medieval

house

which is now a wildflower garden

(All illustrations:

Robin Kent) |

The 1913 Ancient Monuments Consolidation and Amendment Act was the first legislation in Britain to require consent for works to monuments of national importance (scheduled monuments on which a preservation order had been served). Its centenary is a good moment to consider the protection of Britain’s scheduled monuments.

WHAT IS PROTECTED?

The 1913 act built on the 1882 Ancient Monuments Protection Act, Britain’s first heritage legislation, which initiated the shift in legal perception from monuments as private property to the communal shared heritage that we now take for granted. The 1882 act made it a criminal offence to damage any of the 69 monuments detailed on the schedule, which then included earthworks, burial mounds, stone circles and standing stones.

Today’s schedule protects over 200 ‘classes’ of monument, including castles, monasteries, abandoned medieval farmsteads and villages, collieries and wartime pillboxes (churches in use and dwellings are generally excluded). A total of over 34,000 monuments are now included, with more than 200 around the UK being added to the schedule each year out of nearly one million known nationally important archaeological sites.[1] However, the basis of protection provided remains the same as in the 1882 act, and the current act, the Scheduled Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979, requires Scheduled Monument Consent (SMC) to be obtained before carrying out almost any works.

APPLICATIONS

The works which require SMC are comprehensively defined in the 1979 act and summarised as any works that result in demolition, destruction or damage, removal, repair, alteration or addition, flooding or tipping (Section 2(2)). The use of metal detectors also requires prior written consent (Section 42).

Works outside the area outlined on the designation map for the scheduled monument do not require SMC unless they directly affect the monument, but SMC may be required for works to machinery attached to it and the surrounding ground if they could affect the monument (for example by providing support).

Although there is no protection under the act for the visual setting of a scheduled monument to parallel the zones protégés which French monuments enjoy, planning authorities are obliged to adopt a positive conservation strategy and give ‘great weight’ to the conservation of designated heritage assets in local plans and development proposals (Section 12(132), National Planning Policy Framework). Planning authorities also consult the relevant determining body if development affects the setting of a scheduled monument.

|

|

| Ruin of a 16th-century windmill and, below left, the interior of the mill which was converted to a dovecote in the 18th century |

The basic requirements for applications are set out in the act (Schedule 1 to the 1979 act and the Ancient Monuments (Applications for Scheduled Monuments) Consent Regulations 1981). However, the legislation is slightly different in each of the four home countries, and may well diverge further over time, so the current online guidance of the appropriate determining body [2] should always be consulted before applying. Anyone can submit an application for SMC providing the usual notifications are given. About 1,400 are submitted each year [3] and the majority are approved.

Since the preservation of irreplaceable monuments of national importance is the aim, proposals usually require detailed technical consideration and the determining bodies strongly encourage pre-application discussions with the inspector of ancient monuments (or equivalent) for the area. For standing buildings a suitably experienced conservation architect or surveyor should take the lead in these discussions on behalf of the owner and an archaeologist would usually be needed for field monuments. The pre-application discussions and the application itself are free and professional fees for working up schemes of repair can sometimes be grant-aided.

If the monument is also a listed building and the works include alterations, SMC will take precedence and listed building consent will not be required. Scheduled monuments are also exempt from the need for Building Regulations approval or a building warrant in Scotland. However, if the works are part of larger proposals that require planning permission, approval will still be required. This will ideally be dealt with in parallel with SMC, with the determining body (English Heritage for example) liaising with the local planning authority.

Although the level of detail required for SMC applications may in some cases be no more than for a planning application, experience suggests that considerably more is usually required by the determining body to ensure that the proposals are properly described and to safeguard the monument. For standing structures such as ruined monuments, the application is likely to require detailed drawings and specifications at least to RIBA stage E, Technical Design, if not F, Production Information standard. Measured survey drawings may be required to enable this, although annotated photographs can be accepted depending on the nature of the works.

To ensure the heritage significance of the monument is properly safeguarded, other information may also be required. This may include a statement of significance, a condition report, a statement of justification, or an impact assessment and mitigation strategy. Reports may also be required from structural engineers, conservators and ecologists (such as bat and other protected species surveys), as well as from archaeologists. WSIs (written schemes of investigation) or archaeological specifications may also be needed, for example if clearance of overburden or excavation is proposed for footings or underpinning. All this underlines the need for proper professional advice and means that the application can take several months to put together.

|

||

Often preparatory clearance of vegetation, investigative works or trials are required to ensure sufficient knowledge of the monument has been accumulated before finalising the proposals, and these preparatory works may require separate SMCs in advance of the main application. Once the application has been completed and submitted, around four months should be allowed for the approval process (Mynors, p443) but there is no time limit (one application lay dormant for almost five years while the monument changed owners and new proposals were discussed). Fast track digital applications are also available in Scotland but may be time-limited and can result in a refusal if the proposals have not been thoroughly discussed beforehand. Professionally prepared proposals can be processed in as little as two months.

The determining body does not have to consult but, in practice, inspectors often do notify neighbours and tenants, the local authority and specialist bodies such as the Council for British Archaeology, local archaeological trusts, the Royal Commission (in Scotland) and the Ancient Monuments Society, before reaching a provisional decision. The decision, together with any proposed conditions, is communicated to the applicant and must be agreed before SMC is formalised, since there is no appeal after this except to the High Court on a point of law. If agreement cannot be reached at this point, a public inquiry can be held, which can cause delay and additional cost and, as Mynors notes, ‘very few indeed are held’ (p444). The best approach is to ensure that the proposals are fully discussed beforehand.

CONDITIONS

Conditions attached to SMC can specify a time limit (otherwise five years) within which the work must be commenced and by whom, and include specific requirements. These might include the need to notify the authorities prior to commencement to enable inspections, the approval of mortar mixes and other materials, the need for excavations or inspections of particular parts of the work after safe access has been formed, and the need for photographic recording and archiving records of the work.

No work should be started until the formal consent has been received and all pre-conditions satisfied, and this has been confirmed in writing by the determining body. Even after works have commenced, the determining body has extensive powers of access, advice and ‘superintendence’ (Section 25) and architects should ensure that required changes to specifications are recorded to safeguard their liability. Changes in the approved scheme that occur after commencement, such as unforeseen additional work of similar character, can be granted a variation of consent to avoid repeating the application process.

Where grants are being provided, the conditions may also include a maintenance plan usually based on quinquennial (fiveyearly) inspections and there will be public access conditions.

In a few rare circumstances, compensation may be claimed for refusal of SMC or onerous conditions, or if SMC is modified or revoked. If unauthorised alterations are carried out there is currently no legal redress short of criminal conviction but in Scotland the government has recently acquired powers of enforcement similar to those for listed buildings (under the Historic Environment (Amendment)(Scotland) Act 2011).

CLASS CONSENTS

The legislation provides for ten ‘Class Consents’ or exemptions from the need to obtain SMC (The Ancient Monuments (Class Consents) Order 1994). The first of these (Class 1) covers certain works of regular agricultural, horticultural or forestry land management although specific management agreements under Section17 are increasingly preferred as they provide more precision.

Class 4 allows machinery fixed to the monument to be repaired or maintained providing it does not result in material alteration of the monument, and this is increasingly important as more of our industrial heritage is recognised.

One of the most important class consents is Class 5, which permits urgent works in the interests of health and safety, for example if a monument is in imminent danger of collapsing into a busy road. Under its requirements only the minimum necessary work should be carried out, and a letter should be sent to the relevant determining body ‘as soon as is reasonably practicable’ justifying the works. In practice, the earlier the determining body is consulted the better, ideally before the work is carried out.

|

|

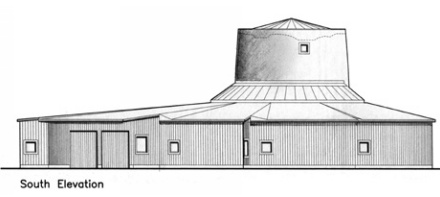

| A proposal for a new house attached to the ruined windmill (see above), which is a scheduled monument. The innovative new use will help to ensure that the structure is maintained for posterity. The work to the monument has been granted SMC and planning permission has been granted for the house. |

Class 9 applies where works are grantaided by the determining bodies. Consent can be granted under this class as part of the grant offer (this is likely to be phased out in Scotland), but parts of the works that are grant-aided by other national grantmaking bodies such as the Heritage Lottery Fund, Rural Development Programme, local authorities or charities will still require SMC.

Works carried out by the determining bodies themselves, for example on the 1,062 monuments they care for on behalf of the nation under ownership or guardianship arrangements,[4] benefit from Class 6 consent but still need written consent internally (one determining body is currently investigating a case of unauthorised works by its own works department). Other monuments owned or cared for by government departments such as the MOD, or agencies such as the Forestry Commission, require Scheduled Monument Clearance (also referred to as SMC and still referred to as Scheduled Monument Consent in Scotland) from the determining bodies in a process which is meant to exactly parallel Scheduled Monument Consent, although without the criminal sanctions.

Under the Planning Act 2008 a development consent order can replace the need for SMC for nationally significant infrastructure projects affecting scheduled monuments although the need for consent prior to works and compliance with conditions still apply (DCMS, Scheduled Monuments, Section 2(27)).

CHALLENGES

Unfortunately the act does not require owners to look after their scheduled monuments. Even though they are our most important national monuments, it is perfectly legal simply to leave them to fall down (although there may be legal implications in terms of public safety and insurance, for example under the occupiers’ liability acts). Nor is there any law that requires owners of other historic or listed buildings to maintain them, and urgent works notices and repair notices do not apply to scheduled monuments. Not surprisingly many are in poor condition. In addition to employing inspectors and other staff, the determining bodies employ small numbers of officers [5] (often known as field advisers or monument wardens) to monitor the condition of scheduled monuments and English Heritage estimates that 17 per cent (3,337) in England are currently ‘at risk’ (about five times the percentage of I and II* listed buildings at risk), while Historic Scotland estimates that over 38 per cent (3,116) in Scotland have ‘significant localised problems’ or worse. There are no tax concessions, VAT exemptions, or other incentives for positive management.

|

||

| Floor plan of the proposed new house attached to the ruined windmill |

Against this depressing picture, grants of up to 100 per cent may be available for repairs to some ‘at risk’ scheduled monuments where a convincing financial case is made, and can include project development costs. There is also the possibility under the act of a monument being directly repaired by the state (Section 5), parts of it being removed for preservation, or the monument being compulsorily purchased or taken into guardianship. However, the stretched resources of government tend to make these cases exceptional. Instead, more co-operative approaches are being explored, such as stakeholder heritage partnerships which build on the provision for management agreements in Section 17 of the act. For example, owners might in future be permitted to carry out certain agreed maintenance tasks without the need to apply for SMC each time. Until the law is changed, however, these will still require SMC.

There are also other grounds for optimism. Increased public mobility and the exponential rise of heritage tourism over the past century have made a few scheduled monuments significant income generators. There is also increasing recognition that ‘the life of a building can be prolonged but not indefinitely’ (Sir Charles Peers, Inspector of Ancient Monuments, quoted in Thompson, p64). Appropriate new sustainable uses may therefore be considered acceptable in some cases, where they preserve the heritage significance of scheduled monuments for the enjoyment and education of future generations. Such solutions often involve imaginative design interventions and even some measure of restoration. Over 500 architects in Britain are now accredited in building conservation, providing a pool of expertise, and there are increasing numbers of other specialists in the private sector with the traditional building skills needed for the repair of scheduled monuments.

A century since the 1913 act, the requirement for consent for works to scheduled monuments tends to be viewed in a positive light by officials because of the advice and grants that are available, but negatively by some owners, who still see SMC as costly bureaucratic interference. It is the job of the conservation architect to find a path between these extremes that preserves and enhances scheduled monuments in a practical and economic way that will bring long term benefits to us all.

~~~

Recommended Reading

British Standards Institution, BS 7913:1998 A Guide to the Principles of the Conservation of Historic Buildings, London, 1998

DCLG, Planning Policy Statement 5: Planning for the Historic Environment, TSO, London, 2010

DCMS, Scheduled Monuments: Identifying, protecting, conserving and investigating nationally important archaeological sites under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979, London, 2010

English Heritage, Scheduled Monuments: A Guide for Owners and Occupiers, London, 1999

English Heritage, A Charter for English Heritage Planning and Development Advisory Services, London, 2009

English Heritage, Conservation Principles, Policies and Guidance, London, 2008

J Fawcett (ed), The Future of the Past, Thames and Hudson, London, 1976

Historic Scotland, Works on Scheduled Ancient Monuments, 2011

Historic Scotland, Managing and Protecting our Historic Environment: What is Changing? The Historic Environment (Amendment) (Scotland) Act 2011 Explained, APS Group Scotland, Edinburgh, 2011

C Mynors, Listed Buildings, Conservation Areas and Monuments, Sweet & Maxwell, London, 2006

M Thompson, Ruins Reused: Changing Attitudes to Ruins Since the Late Eighteenth Century, Heritage Marketing and Publications, King’s Lynn, 2006

Acknowledgements

This article represents the personal views of the author; it is not official guidance, or a statement of the law. Each monument is unique and will require individual consideration and consultation with the appropriate determining body. The kind assistance of English Heritage, Historic Scotland, Cadw and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency is gratefully acknowledged.

Notes

1 The distribution of scheduled monuments is: Scotland 8,201; England 19,748; Wales 4,179; Northern Ireland 1,876 (figures obtained from relevant bodies, 2012). The distribution of nationally important archaeological sites is: Scotland 300,000; England 400,000; Wales 243,984; Northern Ireland 35,000

2 I have borrowed the term ‘determining body’ from Charles Mynors. They are currently: Historic Scotland for Scottish Ministers, English Heritage on behalf of the DCMS, Cadw for the Welsh Government and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency on behalf of the Department of the Environment Northern Ireland (DOENI).

3 Scotland 245; England 1027; Northern Ireland: 40

4 Historic Scotland 345; English Heritage 409; Cadw 127; DOENI 181

5 Historic Scotland 9; English Heritage 16; Cadw 4; DOENI 40