Tin Tabernacles

Liz Induni

|

|

| St Anne’s Mission, New Hedges, Nr Tenby (Tin Chapels Project) |

Tabernacle – a moveable dwelling – a temporary church erected before permanent buildings can be provided

Tin tabernacle – a temporary church of galvanised iron erected by any denomination

In the 19th and early 20th centuries many churches were designed and made in kit form to be bought from catalogues. The most common type was timber framed, externally clad with galvanised corrugated iron (CI) and lined with high quality tongue-and-groove boarding. Many of these simple ‘tabernacles’ had high levels of decoration: outside, timberwork was often richly carved; inside, panelling and other surfaces were usually enriched with delicate stencilling. These were excellent buildings which proved surprisingly durable.

Tin churches may meet few of the rules of ‘great architecture’, but they tell us as directly as any others about the aspirations, fashions and economic privations of ordinary people. Most have rich associations in local memories. People will talk for hours on their fond recollections of dance night at the parish hall or the Jubilee tea…

|

|

| St Saviour’s, Faversham, Kent from an early 20th

century postcard (Collection of John Bray) |

|

|

|

| "This syle of Church is avaialable either for

temporary use or permancy" |

HISTORY OF CORRUGATED IRON

The principle of folding or corrugating sheets of iron to add stiffness and rigidity had been known long before corrugated iron began to be produced on a large scale in Britain. In the early 19th century three developments made this possible. First was the 1820s development by Henry Palmer, a civil engineer in London, of a new method of corrugating iron; second, Richard Walker’s realisation that Palmer’s process enabled the production of a cheap, light-weight cladding system that was ideal for iron framed buildings with a large span, such as warehouses; and third, the invention of hot dip galvanising in 1837.

By the early 1840s several manufacturers were producing corrugated iron using the system used today in which red-hot sheets of wrought iron are passed through a rolling mill, rather like a washing mangle with interlocking rollers. The distance between the two rollers could be adjusted to make sheets of various thickness. Until the 1880s individual works had their own gauges and the main centre of production was the Black Country, in the West Midlands.

Galvanising, the process of coating the surface of the iron with a layer of zinc which was patented in 1837 by a French engineer Stanislaus Sorel, dramatically increases the, resistance of the iron to corrosion, transforming it into a long lasting material. Despite the popular description of CI buildings as ‘tin’, as far as is known, only zinc was ever used as a surface coating. In Britain, true tin plate was reserved mainly for the canning of food.

The Industrial Revolution had brought an increasing demand for large industrial buildings. Traditional roofing materials, such as tiles and slates, were not suitable for large spans, particularly where the roof pitch was shallow, because of the excessive weight load. Some early roofs were covered with sheet iron (a late example of this type of construction can be seen at the Pump House, Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire which has now been restored), but corrugated sheets were lighter and more rigid, enabling them to span between beams unsupported. The corrugations also meant that the sheets could be overlapped to form an interlocking, watertight roof. Whole sheets could be curved at right angles to the corrugations to make rigid arches. Huge spans of, for example 100 feet could be covered by two or three arches of corrugated iron.

The new construction system was ideally suited to prefabrication. It was light, strong, compact and able to be cut into sheets of a manageable size. Increases in population, colonial expansion and mass emigration in the 19th century created a need for ‘flat-pack’ buildings which could be made in Britain and transported abroad. Corrugated iron buildings met this need.

Richard Walker, who had a works in Bermondsey, was instrumental in developing the technology of CI building manufacture. Charles Young of Edinburgh produced buildings that were listed in the catalogue of the Great Exhibition of 1851, where some of them were erected for display.

THE AGE OF IRON

In the Victorian era developments in manufacture meant that iron could be made cheaply and accurately on a mass scale for the first time. In 1851 the construction of the Crystal Palace, a vast structure of iron and glass, epitomised this new Iron Age.

While some architects – and engineers in particular – were not slow to see the possibilities for the use of iron in architecture, not everyone admired it: John Ruskin condemned the material in his seminal book, the Seven lamps of Architecture, and the Arts & Crafts Movement which he inspired followed his lead, preferring traditional construction methods and materials. Corrugated iron was a revolutionary new use for the material and the limits and rules of building technology had to be revised for it to win acceptance. Many architects still shied away from using it and never accepted corrugated iron as anything other than low status and temporary.

|

|

|||||

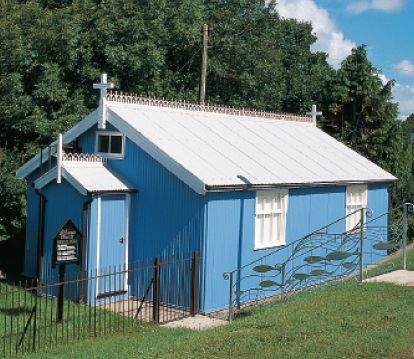

| All Saints, Dilton Marsh, Brokerswood, Nr Westbury, Wiltshire (Tin Chapels Project) |

Breadstone Church, near Berkley (courtesy Phil Draper, Tin Chapels Project) |

CHURCHES

The very rapid growth in urban population during the Victorian era caused a new wave of church and chapel building. The advocacy of traditional materials by the Ecclesiological Society and architects such as Pugin, Street and Scott was irrelevant to the church needs of the poor or those at the margins of society. It was especially irrelevant to those settling at the frontiers of new lands in America and throughout the British Empire, and to the roving missionaries of every denomination.

In response to overwhelming pressures to provide cheap, rapidly erectable buildings that could be sited far from developed sources of traditional materials, it is no surprise that CI buildings started to be mass-produced by engineers and builders. They were made available for sale through catalogues. Each building type – cottage, railway station, church or house – was illustrated with a drawing and a price. Size could be altered according to need.

Prefabricated iron churches were relatively cheap to buy, costing anything from £150 for a chapel seating 150 to £500 for a chapel seating 350. Conventional building materials for the same would be considerably more expensive.

By 1875 hundreds of CI churches were being erected, many with extensive gothic style embellishments.

CONSERVATION AND REPAIR

|

|

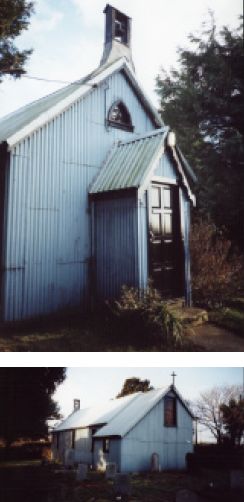

| Henton Mission Church, reconstructed at the Chiltern Open Air Museum (photo Chiltern Open Air Museum) | |

|

|

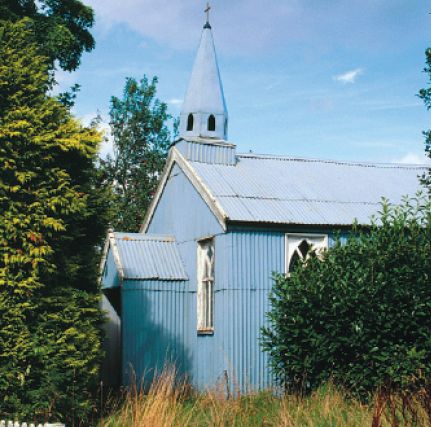

| Dottery Church, a surviving tin tabernacle at Dottery, Bridport, Somerset (Liz Induni) | |

|

|

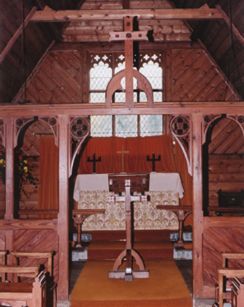

| The timber panelled interior typical of a prefabricated Victorian church, although this one at Sandy Lane, Wiltshire has a thatched roof. |

Corrugated iron churches are easy to mend because of their simple construction. They are generally constructed with foundations of brick supporting the timber frame, separated by a damp proof course of natural slate. As with timber framed buildings the frame is erected in bays. The roof trusses line up with the vertical posts in the wall panels. CI sheets are fixed with nails on the exterior of the timber frame or sometimes with hooks around the frame on the inside and fixed through the CI sheet by bolts and washers on the outside. The sheets overlap so that the rainwater runs off the building (not into it). Outside corners are constructed so that the corrugated iron wraps around the corner. The interior is usually finely finished in tongue and groove pine boarding and often decorated in elaborate stencilling.

PROBLEMS

Cladding (roof and walls)

The inherent weakness of corrugated iron sheeting is that of corrosion, particularly around the nails holding the sheets to the frame. Once corrosion has begun, it is practically irreversible. This corrosion will not immediately cause a weakening of the building but it will allow the ingress of water causing damp and eventually the decay of the timber framing of the walls and roof. In some instances it may be possible to cover minor holes with off-cuts of CI sheet, but for more significant damage there is usually no alternative to replacement.

The sheets are easily taken off by removing the nails on the outside of the building. Replacement sheeting can still be obtained, although the modern sheets are generally thinner than those made in the past. Take care to check the profile and size of the corrugations.

Painting

When painting over new galvanised sheet you must allow time for the galvanised coating to wear down – about six months – or the paint will peel off. Alternatively it may be acid washed to provide a key for the paint. Old sheets which are to be reused must be cleaned down as thoroughly as possible, removing any flaking areas of paint, but retaining sound areas of paint. Areas where the paint has been removed may be primed with layers of good quality zinc-rich paint. This paint may also be used as a primer for new sheets to deaden the galvanised coat. The primed surfaces (new and retained CI sheeting) may then be undercoated and gloss finished.

Windows

These are unlikely to carry any structural loads (unless something has gone badly wrong), but will fit within the timber framework of the building. If a window frame is rotten in parts it may be possible to remove the frame and repair the damaged pieces, retaining the healthy parts of the frame. Repaint with primer, undercoat and gloss to match the other frames.

Guttering

All rainwater goods need to be maintained in good condition, as water ingress is the main threat to the building. Faulty down-pipes should be replaced with replicas and drainage from the site should be thoroughly checked to ensure that it is working effectively.

Interiors

Most corrugated iron buildings have tongue and groove pine boarding inside. If the board is rotten, broken or damaged, it can be easily removed and replaced. If the original is painted, match it with a suitable primer, undercoat and top coat.

Stencilling

If you are fortunate enough to have stencilling in the form of lettering or decoration, then treat it sympathetically. These delicate and beautiful decorations are often the highlight of the buildings. Do not be tempted to paint over them and obliterate them.

REPAIR OR REPLACE?

With traditional old buildings it is preferable to repair than to replace: original 19th century windows, for example, should have their timbers repaired where necessary, splicing in new timber and they should not be entirely replaced with new wood. The small decorative details are vital to the overall design. It is essential that these are repaired and replaced like for like. The building only needs to lose two or three of these decorative elements and it quickly starts to look like a garden shed.

The cladding on CI churches presents a different problem. Although the cladding is a key component and therefore of historic value, it is not really practical to consider conserving large areas of damage. However, deterioration often looks worse than it is. At Tenbury Wells, for example, 90 per cent of the galvanised sheeting fitted in 1911 was found to be re-usable, despite its poor appearance. It was cleaned down, powder coated and re-used in a recent conservation programme.

In the case of the tin tabernacle which now stands at the Chiltern Open Air Museum (illustrated opposite) all the CI sheeting was saved, along with 90 percent of its fixings, and the sheeting was cleaned back to bare metal before being repainted.

This mission hall, which dates from 1886, was moved to its present site in 1993 from Henton near Chinnor in Oxfordshire where it had lain derelict for many years. The careful dismantling of the structure by museum volunteers took 12 days to complete. All the floor joists and bearers had to be replaced due to wood worm damage; several of the windows also needed to be repaired, particularly the cills, as did the ventilation louvers and some minor repairs were needed to the frame; some components had been lost, mainly as a result of vandalism, including the porch, the floor boards, and most of the iron ridge cresting was broken; some of the panelling inside had been set alight by the vandals, and only the base of the bell turret had survived. Nevertheless, the remaining structure and the cladding had survived remarkably well. Alterations were kept to the minimum necessary and missing elements were reinstated based on reliable evidence, which included photographs.

USE IT OR LOSE IT

When a building is not used, it rapidly falls into disrepair, and corrugated iron churches are often simply abandoned. However, CI buildings are more versatile and adaptable than others. The timber framework and removable cladding makes them readily convertible. Externally, the building can be extended by adding extra framework and cladding. Internally, because the divisions are often lightweight studwork, it is easy to add or take away partitions. Because they are so versatile, many of these buildings have had a change of use without any apparent damage to their structure. A church can become a village hall, a dance hall or a Masonic lodge without any alteration being made to the exterior. As a last resort, they are also highly moveable: recycling a tin tabernacle must surely provide the ultimate in sustainable development.

AWARENESS AND PROTECTION

In this country, numbers of corrugated iron churches have dwindled rapidly, and few remain in their original use. People perceive them as cheap and temporary regardless of their age. When they are not maintained they decay rapidly and are pulled down, not because they are falling apart, but because of people’s perception of them as ‘old, temporary and not proper’.

Very few of these tin tabernacles have achieved the status of being listed. Usually 19th century buildings are listed only if they are relatively ‘complete’ – that is to say with original features intact – thereby giving little hope to buildings of changed use. Conservation areas offer very little protection. Yet these buildings are an intrinsic part of out cultural heritage and must not be passed over as if they were of no consequence.

Corrugated iron churches must not be forgotten.

RECOMMENDED READING

Herbert, Gilbert Pioneers of Prefabrication

See also www.tintabernacles.com – an informative and superbly illustrated website maintained by Ian Smith,

Tin Chapels Project, Camrose Organisation, Camrose House, 106 Main Street, Pembroke SA71 4HN

Tel 01646 680505 Fax 01646 687142