Fire Damage and Reconstruction

Justin Fenton and Iain King

|

|

| Glasgow School of Art: the exterior after the fire (Photo: Page\Park Architects) |

On 23 May 2014 outside the Glasgow School of Art, dismayed onlookers including students, staff and members of the public looked on as black smoke scarred the skyline. The impact of the fire was far-reaching. In an interview with the press immediately after it, chair of the board of governors Muriel Gray emphatically declared that the school would ‘rebuild the library exactly as it was’. It was an unfettered response.

A fire in a historic building defines the end of a past, it dominates the present, and it triggers a new and uncertain future. The challenge for any reconstruction project is to establish and maintain the delicate balance of these three chronological elements. Each must be given equal weight; it is important to avoid diminishing the past or monumentalising the fire.

A HARD BEGINNING

According to the poet and playwright John Heywood (1497-1580), ‘A hard beginning maketh a good ending’. A fire in a historic structure need not be considered a tragedy exclusively. In the right circumstances it can also be an opportunity with the potential to bring new life to a building.

Before the fire at the National Trust’s Clandon Park House in Surrey in 2015, visitor numbers were dropping steadily, year on year. Although much of the house interior was destroyed, its remnant structure is now the subject of a £30 million international design competition with a brief to transform the visitor experience and raise Clandon’s profile.

Without the fire this investment in the building, its fabric and its future might not have been forthcoming. Nor would it, perhaps, have been undertaken in such a creative and uninhibited manner.

The Glasgow School of Art can be viewed in a similar way. While the Mackintosh Building was a source of identity for the school, its building fabric was increasingly struggling to meet the demands of a contemporary educational environment. This was compounded by an increasing requirement for public access. For example, access to one of the school’s key rooms, the library, had been restricted to safeguard its interior.

For how long could the building have continued to function without compromising its fabric? Or would restricted public access inevitably have resulted in the building becoming redundant or an artefact in itself? Arguably, both buildings were failing to fulfil their potential in terms of public use and this had placed their long-term future at risk. In both instances, tragedy has facilitated a radical re-thinking of the approach to stewardship, management and development of the assets for their owners and stakeholders.

Change is inevitable and the objective of this type of conservation project then becomes the process of managing change in ways that will best shape and sustain our historic environment, allowing people to use, enjoy and benefit from it without compromising the ability of future generations to do the same.

UNDERSTANDING VALUE

In order to manage change and inform decisions about the future of a place, it is first necessary to understand and articulate its significance. While prior to a fire much of the historical, aesthetic and design value will have been long established, it must be reassessed in the fire’s aftermath. Although historical authenticity can never be regained once it has been lost, the formal characteristics of a work of architecture may be recovered through reconstruction or restoration.

|

|

| South elevation, laser scan of library (Image: Glasgow School of Art) |

Public reaction to the devastation at the Glasgow School of Art demonstrates how historic buildings can carry a powerful emotional charge. This can intensify over time as people’s association with a place takes on new meaning, becoming a part of its history and character as a source of cultural identity.

The reaction of the chair of the board of governors suggests that the significance of the whole is inextricably linked to its integrity as a composition. Emotional, certainly, but carrying a certain academic weight, such a response can easily become the driving force for an attempt to recreate a lost place of symbolic value. So which is more important, built heritage or cultural identity?

The success of any reconstruction relies on understanding those intangible values that contribute to public affection, ensuring that they are upheld through the reconstruction. They may endure the replacement of the original physical structure, so long as its key social and cultural characteristics are understood and maintained.

Restoration is only a valid response where there is sufficient evidence to reproduce an earlier state of the fabric. Thus it is important to gather as much evidence as possible: written and drawn archives, measurements and photographs, conjecture and interpretation.

A fire can diminish or destroy, but it can also reveal layers of history that have long been forgotten and original designs or historic construction methods can begin to be communicated. In some respects, these discoveries have the potential to yield information about the past and can offer a new understanding or interpretation of a building, prompting new research and investigation.

A greater emphasis is required on the precious fabric that remains in order that it might be saved. Preservation and change are thus integral to the conservation of fire-damaged buildings and neither is mutually exclusive.

To balance the effect of the loss of the original fabric, the opportunity for a new understanding should also be realised in the reconstruction. This approach invariably recognises the potential of change to reveal and reinforce value.

CONSERVATION METHODOLOGY

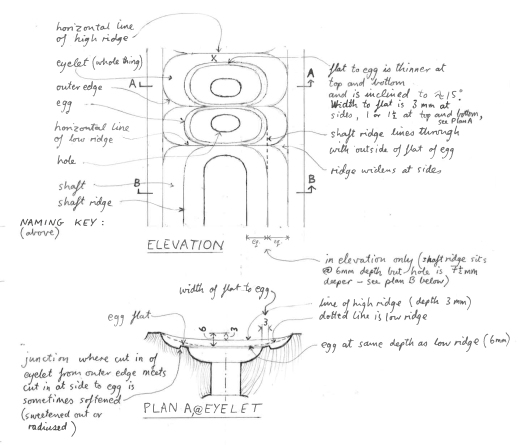

At the very beginning of the Glasgow School of Art project it was established that a complete reappraisal of how we manage, analyse and, most importantly, make use of the large quantities of archival and archaeological information to enhance the quality of the reconstruction, was required.

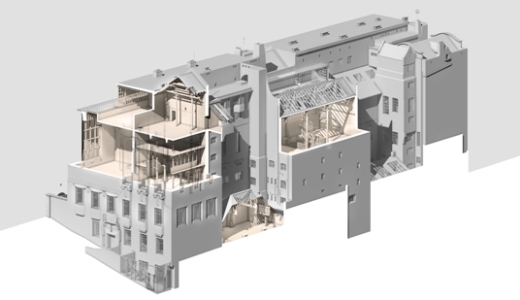

The solution was to develop a cyclical working process, employing laser scanning and 3D modelling with building information modelling (BIM) as the binding element of three main areas of focus: research, production information and construction. Rather than viewing these as distinct categories, they were identified as three working areas, all of which must inform one another, and all of which have a unique output.

|

|

| Detail of library carving (Image: Page\Park Architects | |

|

|

| Cutaway render of BIM model (Image: Page\Park Architects) |

Library The research area of focus was called the library, because it is a growing resource that can be referred to throughout the project. It contains the exploration and collation of relevant archival sources to enhance the quality and accuracy of the reconstruction. As an output, we create a comprehensive set of documentation which informs our conservation philosophy and records the condition of the building, the works required and recommendations for the future.

Studio The production of technical and design information is called the studio. It is where BIM comes into play as a design tool and repository for all project knowledge. This work relies on the outputs of the other areas to inform what we design, draw and build. The result is a comprehensive BIM model which can be used for facilities management and as a future learning tool.

Workshop This is the live site environment, where intelligent and informed proposals are thoroughly tested, developed and finally realised. Lessons learned from physical prototyping feed back into our working studio to refine proposals.

This process is cyclical because no element is ‘complete’ until the end of the project. Rather, the main focus shifts throughout the project timeline. Everything that is learned from archive research and from real-world sampling and testing feeds into the building information model.

The work in each area should never take place in isolation, rather it should constantly enrich the output of the others. The end-goal is to deliver not just a comprehensive and seminal historic reconstruction, but also highly detailed building information as a future heritage asset.

One of the most important parts of the Glasgow School of Art project is the reconstruction of the library. It is the area of the project that best illustrates our approach to information management and BIM integration.

Just as each timber element exists as a separate component, it is modelled as a separate component in the digital environment. It is then tagged with a unique reference number and multiple fields of information relating to it. For example, by clicking on a specific timber in the model, it is possible to access not only information about its physical properties, but also what evidence existed to justify the reconstruction of that element. Any photographs, archaeological detail or survey data relating to the element are embedded in the model. The result is an interactive conservation tool which justifies in fine detail the evidence-base for reconstruction and supplies in-depth practical information to the contractor.

In order to interpret and assess the significance of the information, the methodology described below was established.

From the outset of the project, a view of what is currently known must be assembled. In broad terms, this can be described as:

- original intention

- pre-fire knowledge: what has changed since the original construction?

- post-fire knowledge: what did we learn from the fire, fire-spread and underlying construction?

From this knowledge we can begin to assess and understand the consequences of the fire, which can be categorised as:

- repairable: elements of existing fabric that can be retained

- damaged: fabric which has been partially lost but is sufficiently intact to be analysed and measured to inform a faithful reconstruction in new material (physical evidence)

- destroyed: fabric which has been completely lost.

From this accumulated knowledge, all parties can assess, understand and grade the significance of the elements to establish conservation policies. At the Glasgow School of Art we considered this from the macro to the micro:

- understanding the fabric of the building as a whole

- understanding on a room-by-room basis

- understanding on a piece-by-piece basis.

These policies give direction, serving to define the key conservation principles and objectives of the project. They are also used to support the client’s brief, aspiration and vision beyond the immediate reconstruction. As we work through the various areas of the Glasgow School of Art we review and consider all aspects on an individual basis. The established conservation policy thus becomes a constant point of reference to ensure the integrity of the whole is maintained.

LEGACIES

The conservation of a fire-damaged historic building brings with it a complex dynamic which can seem at odds with a conservationist’s raison d’être. The loss of original fabric necessitates change and this can be to the wider benefit of the building because it requires owners and stakeholders to rethink their stewardship of the heritage asset. Often this future vision, to safeguard what remains, is realised in a manner which is creative and uninhibited. This can be seen in the developing proposals at Clandon Park.

|

|

| One of the six innovative shortlisted design concepts for the restoration and rebuilding of the National Trust’s Clandon Park House, Surrey (Image: AL_A and Giles Quarme & Associates with Arup and GROSS.MAX) |

Invariably the building’s status also changes as a consequence of a fire, as historical and architectural value will have been compromised. The often intangible social value of the building is manifest in the public reaction to the loss. That reaction can be the necessary stimulus which ensures the recovery and future prospects of the damaged building.

The conviction and depth of feeling from the public can be so strong that it establishes new parameters to which significance and value are attributed going forward. It can focus the conservation strategy where it matters to the people and their memory of a place. Consequently, if this is reinforced in the reconstruction then there is a greater possibility that the project will be considered a success.

The destruction of a building’s fabric leaves behind much evidence which can yield new information and provide an alternative understanding of its heritage. It then becomes the responsibility of the design team to ensure this knowledge is enhanced, communicated and reinforced as it is likely this will precede the relative significance of the finished work. This must be done in a manner which is accessible and engaging to ensure that the legacy of the building endures beyond the reconstruction.

On the Glasgow School of Art Mackintosh Building restoration this is being done by pioneering new means to document and record the reconstruction process, principally through the use of BIM. While BIM is commonplace for new-build construction, its use on heritage projects is in its infancy. (At the time of writing the only comparable enterprise is the Elizabeth Tower at the Palace of Westminster.) It is the single-source repository for all our research, findings and discoveries; it is a live ‘document’ built upon throughout the project and beyond.

The building information model can be used by the contractors who are undertaking the reconstruction and this is bringing an added level of sophistication and refinement, allowing the building to be better understood.

Its full potential post-construction is yet to be realised but we are already seeing the benefits of adopting this technology, which supports new forms of understanding, interpretation, recording and assessment.